In this week’s newsletter, we talk with Michael Anastassiades about the concept of “slow appreciation,” pick up a posthumously published book of Joan Didion journal entries, look forward to the sixth edition of Beatrice Galilee’s The World Around Summit, and more.

Good morning!

Ever since I came across the work of the Lebanese-born, Paris-based architect Lina Ghotmeh—around 15 years ago, after she and two other young, enterprising moonlighting architects won a competition to design the Estonian National Museum, a building they later completed in 2016—I’ve been in awe of her visionary “archaeology of the future” design approach. I was one of the first journalists to report on that museum, and I later featured it in my 2020 book, In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials (Phaidon). In 2023, I interviewed Lina for this newsletter when she was the designer of that year’s Serpentine Pavilion in London. Yet, while Lina and I have kept in touch over the years, until the recording of this week’s episode of Time Sensitive, we’d never met in person.

The resulting conversation was exactly as I’d hoped it would be: To speak with Lina is to somehow experience her evocative, moving, and essential-feeling buildings and spaces. It wasn’t so surprising to me when, just a week after Lina was in the studio, she was announced as the winner of a competition to design the British Museum’s Western Range, which holds a third of the museum’s overall gallery space, and, shortly after that, she was named the architect of the new Qatar Pavilion in Venice’s historic Giardini. This week, she unveiled her Bahrain Pavilion at the 2025 Osaka Expo in Japan, and she’s also currently at work on the design of a contemporary art museum in AlUla, in Saudi Arabia.

So what is it that makes Lina’s architecture so special? For me, it’s the high-touch, high-craft nature of what she does. I think it’s fair to say that her architecture is, at its heart, a celebration of the hand. For Lina, sustainability is as much about the quality of a building’s materials and construction as it is about its emotional, social, functional, and utilitarian layers. There’s also an aspect of light and lightness to her work—something we get into on the episode, talking about her new book, Windows of Light (Lars Müller Publishers), as well as the exquisite Czech glass light sculptures she created for The Okura Tokyo hotel’s 2019 overhaul and revamp by the late architect Yoshio Taniguchi.

I suppose light has been on my mind lately: This week’s Interview With, below, features a conversation I had recently with the designer Michael Anastassiades, known for his highly refined lighting creations.

In our oversaturated world full of visual clutter and noise, I view Lina and Michael as literal and figurative guiding lights. Both are big-picture creators who bridge beauty, humanity, and harmony in all that they do and, in turn, make the world a bit brighter in every sense of the word. I suppose we could call their practices “light-minded.”

—Spencer

“Technology, sustainability, and the environment at large are brought together at once when we are engaged with craft. It’s not a backward-thinking mode.”

Listen to Ep. 129 with Lina Ghotmeh at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

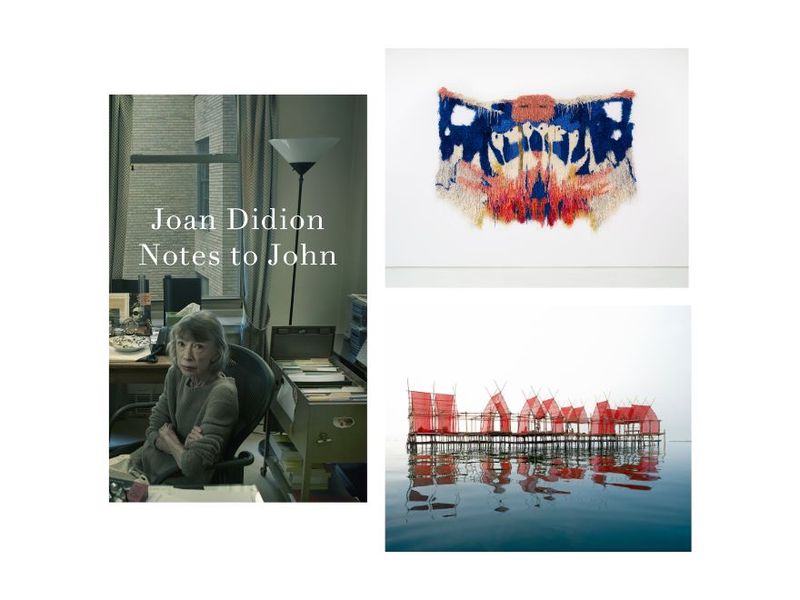

Notes to John by Joan Didion

During what she would later describe as “a rough few years” in 1999, the writer and essayist Joan Didion began keeping a private journal following sessions with her psychiatrist. These notes explored recurring themes in her life and work, ranging from anxiety, alcoholism, guilt, and depression to reflections on her own childhood and her complicated relationship with her daughter, Quintana. Like any diary, Didion’s introspective and raw entries served as a means of unpacking and better understanding her interior self. Over time, though, they became something even more enduring: self-examinations of her suffering and survival. The forgotten journal was found in a filing cabinet in Didion’s apartment in 2021, and now, nearly 26 years after she began writing in it, the texts—addressed to her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne—form the foundation of Notes to John (Knopf), out April 22. The result is an intimate and tender posthumous window into the mind of one of America’s sharpest, most luminous authors.

“You Stretched Diagonally Across It: Contemporary Tapestry” at Dallas Contemporary

“You Stretched Diagonally Across It: Contemporary Tapestry,” a new group exhibition at Dallas Contemporary (on view through October 12), reimagines tapestry as a traditional medium through an increasingly modern lens via the works of 30 contemporary artists, designers, and makers. Taking its title from Franz Kafka’s “Letter to His Father”—in which considers his father’s presence stretched, almost threadlike, across a map of the world—the exhibition, curated by guest curator Su Wu, invites both acclaim and analysis as viewers think about the art of tapestry not only in the physical sense, but as a broader metaphor for memory and meaning amidst our dwindling attention spans and growing digital overwhelm. Featuring works by the likes of Caroline Achaintre, El Anatsui, Diedrick Brackens, Sanam Khatibi, and Candice Lin, “You Stretched Diagonally Across It” honors the historical importance of weaving while also contemplating its grounding role in the present.

The World Around Summit at the Museum of Modern Art

In 2020, Beatrice Galilee—a curator, writer, and the former associate curator of architecture and design at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—founded The World Around, a conference that advocates for and advances critical architectural and design conversations and ideas. Now in its sixth cycle, The World Around Summit will return on Sunday, April 27, this year at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, for a full day of presentations and programming highlighting various design projects, initiatives, and ideas shaping, yes, the world around us. Galilee tells us that the daylong conference, curated with the Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment, will feature presentations and moderated discussions from the Indigenous Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal; Chatpong Chuenrudeemol, of the Bangkok-based firm Chat Architects; South Korea’s first licensed female architect, Jung Youngsun; and Elizabeth Diller (the guest on Ep. 9 of Time Sensitive), among others. Though the event is sold out, true to The World Around’s name and credo, it will also be livestreamed for anyone to enjoy.

During Milan’s Salone del Mobile design and furniture fair earlier this month, the designer Michael Anastassiades unveiled a suite of new collaborations: urn-like planters for Monstruosus, inspired by Mediterranean olive oil and wine vessels; linked vertical glass lighting pieces for Flos; updated elements for B&B Italia’s Jack bookcase system; and geometric chairs for Tacchini that fit together like puzzle pieces. At the Jacqueline Vodoz and Bruno Danese Foundation, he also presented an exhibition of his own lighting creations, including the Cygnet light, stemming from his childhood memories of building and flying kites.

Today, Anastassiades is one of the design world’s more prominent fixtures (pun intended), but his was a circuitous journey to this point. Earlier in his career, he was known for his humorous concept pieces such as the Message Cup (1995) home-recording device; the Anti-Social Light (2001), which dimmed in response to conversation (and the Social Light, also from 2001, which worked in reverse); and Design for Fragile Personalities in Anxious Times (2004), a collection of playful pieces meant to soothe existential dread. In 2007, when Anastassiades launched his own lighting brand, he quickly proved himself to be of rare talent when it came to harnessing the power of light through trademark fixtures that manage to both stand out (for their clarity, simplicity, and precision) and disappear into most any setting.

Here, the Cyprus-born, London-based designer shares how embracing the unknown has long defined his unorthodox design approach.

During the early, more experimental years of your practice, you taught Ashtanga yoga. What connections, if any, do you see between yoga and design?

I discovered Ashtanga yoga in the early nineties and got hooked. After a few years, a friend said, “You should teach. You’re good.” She got me a private client who was going through the early stages of divorce. During the first practice, the client broke down in tears, and I said, “Are you okay? What’s going on?” Yoga brings out all of these emotions. She said, “I’m not really well.” I became a therapist and teacher, but I was well paid. That was the way I could actually support myself while keeping my design ideas pure.

The connection between design and yoga? There’s always a connection somewhere. But here, it just made sense for practical reasons: It gave me money. When I graduated from the Royal College of Art, I came to New York to get a job. I graduated with the oddest pieces. One of them was the Message Cup. The concept was that each person in the house would have their own cup. If people want to give a message to somebody, they pick up their cup, and they put it face down on the table. When the person comes home and finds the cup face down on the table, then they know there’s a message there. I knew that nobody could possibly hire me or offer me a job in design, so I decided to set up my own business. I wanted to discover what design is for me.

Your practice, like yoga, is predicated on this idea of being open and embracing the unknown.

Through curiosity, I got to where I am today. The idea of not knowing helped me have no inhibitions in terms of trying things. I said, “I’ll try. It doesn’t matter. If it works, it works; if it fails, it fails.” I was not scared of failure in that sense.

My first light was—

The Anti-Social Light.

Yes, it was a light that worked only when there’s absolute silence. When you talk around it, the light beams down, and then eventually switches off, and then you have to be silent to get it to start flowing again and beam up. Slowly, after [everybody] being quiet for a while, it starts coming on. I also did the Social Light, which was exactly the opposite: You needed to talk to it to keep it on.

You frequently collaborated with Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby. Could you share a bit about Dunne & Raby and the projects you did together? One of them was called Designs for Fragile Personalities in Anxious Times—relevant today, I think. It comprised Huggable Atomic Mushrooms and Hideaway Floor Furniture. How did working with them shape you, your thinking, and your practice?

Tony [Dunne] was my professor at the Royal College. He didn’t fit in, so I thought, This guy is interesting! A few years after I graduated, we reconnected. We were very frustrated about what design was at that time and what was happening around the world. It seemed that most interesting, beautiful, experimental design had died in the sixties, and there were no new radical ideas. Everybody was doing very conventional things. We decided to do a project together.

The first was this collection called Weeds, Aliens, and Other Stories, a series of furniture pieces and electronic products inspired by the obsession that British people had around gardening. There were these labels that would talk to your plants when you were away on holiday; they would read poetry, or sometimes recipes. We had these living room tables that had a drawer where you would plant cucumber seeds and have the cucumber grow straight into this “cucumber straightener.” We had a fence where you would grow grass on it, and then when you had a fight with your partner, you would sit on either side and negotiate over the fence. It was crazy. It became an exhibition in Prague, and then at the ICA in London and in several other museums, and eventually the whole collection was acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum.

That’s when we did Designs for Fragile Personalities in Anxious Times. The idea behind the Huggable Atomic Mushrooms was that you would hug it to heal yourself from the fear of nuclear war by becoming familiar with it. This is now in the permanent collections of both the Art Institute of Chicago and MoMA.

I wanted to bring up an early breakthrough moment from 1998 at a design fair in London. There, you met Ilse Crawford [the guest on Ep. 107 of Time Sensitive], as well as the design gallerist Murray Moss. Tell me about each of them and how they impacted your career.

Back then, I was looking into any ways to establish myself as a designer. I applied for this grant from the Crafts Council of England. I was not a craftsman. I’d never made anything, but I applied for this grant, and if I got it, I thought I would maybe set up a workshop, learn how to make things. I got the grant. Part of the deal was that I had to have an exhibition.

I made these very experimental pieces—I didn’t make them physically; I had my carpenter do that—and the first person who walked in was Murray Moss. He said, “Very beautiful. Is this for sale?” I said, “No.” He said, “Is this for sale?” I said, “No.” He said, “Is anything here for sale?” I said, “No.” He said, “Then why are you here?” I said, “I don’t know. I’m not selling anything.” So he said, “Well, if any of these pieces ever go on sale, please let me know. Here’s my card.” I had no idea who he was.

Ilse was another one. She had decided to quit this incredible role that she had as the founding editor of Elle Decor U.K. She had made that title what it deserved to be, and eventually, she had been appointed by Donna Karan to lead her homeware line, because all the fashion brands were starting homeware lines at that time. Ilse walked in my booth, and she said, “Would you like to join me to do this? Maybe we could design for Donna Karan?” I said, “That could be interesting.” We became friends.

I bring up Ilse and Murray because years later—in 2007, at age 40—you went on to start this very successful lighting business. Murray was selling some of your earliest lights and Ilse was pushing you forward, in some sense, saying, “You’re really good at making lights; you should do this.”

In 2006, I decided to have an exhibition. Before I had that show, I went to visit Ilse and said, “I’m making things now. Can I show you?” The next day, she said, “I want ten of these fixtures for this project, and I want this, and I want that.” Later that week, I had my opening. She came again. She loved everything. Then Murray Moss turned up again. This time I knew who he was. He said, “I want two of these, three of these, ten of these, five of these.” That’s when I decided to set up a lighting brand.

Embedded in your work is the idea of making designs that stand the test of time. You follow what we might call a “fewer, better things” approach, and materially speaking, your work is about celebrating the purest sense of the material.

My approach has always been to be honest in the way that you communicate material; be honest in the way you try to simplify design, try not to shock the people with your language because I believe that shock is an easy trick. Design should not be about this.

For me, design needs to be a slow appreciation. The first time you see the object, it looks familiar. You’ve seen it before. You don’t know, is it new? Has it existed? It feels comfortable, and then it feels part of the space then, or it’s invisible—even better—as a thing. Then the second time you see it, you start noticing it again, and you think, That’s interesting! Then the third time, you discover something else. I think this slow appreciation and build-up over time is what makes you appreciate the object. A lot of people can’t believe a fixture is twenty years old, because sometimes they never notice it. For me, this is the biggest compliment. That is what design should be. Don’t get me wrong, I have great admiration for examples where designs shock the world. But it’s not the way I do it.

Let’s end our conversation on the subject of rocks. You have a massive rock collection, and I wanted to ask, why stones? What have you learned through collecting them and spending time with them?

I started collecting stones as a child. I grew up by the sea, and I loved to spend time in the water. I used to feel hard shells or stones through the soles of my feet. I was trying to figure out the shape of them. I learned to grab them and appreciate their shapes.

When I look at this enormous collection I have today, something that links most of them is that they search for the perfect shape, which goes against nature. With nature, it’s unpredictable. I was always looking for the perfect spherical stone that would have been created naturally. I’ve always had this fascination about the role of nature as a designer.

I never worked with natural materials—it was always fabricated sections, working with metals, mainly—until I did this collection with the bamboo. It was quite a fascinating moment for me. I wanted this dialogue between the bulb, which I had an obsession with, and the bamboo itself as a natural material that you have to choose when to cut, which is exactly at the moment when it reaches the exact diameter of the bulb. There is a dialogue between the bulb and the bamboo; it’s a perfectly straight line. How do you actually have that discipline in nature? I think this probably explains my obsession. For me, that sense of discipline in nature is what attracted me to stones in the first place.

This interview, conducted by Spencer Bailey, took place at the textile company Maharam’s New York City showroom on March 20, 2025, in front of a live audience. It has been edited and condensed.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

On April 22, The New Yorker’s fiction editor, Deborah Treisman, will join the novelist Jennifer Egan in conversation at New York’s Rizzoli Bookstore to celebrate the recent release of A Century of Fiction in The New Yorker: 1925-2025 [Rizzoli]

Nearly 30 years after its inaugural retreat took place in Esopus, New York, Manuel Betancourt tells the story of how Cave Canem—the annual literary workshop and summer camp for Black poets—came to be [Los Angeles Times]

With “Amy Sherald: American Sublime,” the artist and painter Amy Sherald—whose first solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art includes portraits of Breonna Taylor and the former first lady Michelle Obama—considers a complicated, all-important question: What does it mean to be American? [NPR]

The actor and musician Jeff Bridges delves into his new album, Slow Magic: 1977-1978, in a conversation with Amanda Petrusich [The New Yorker]

The comedian Ramy Youssef talks with Lulu Garcia-Navarro about representation, expression, and emotional connection in comedy [The New York Times]