In this week’s newsletter, we interview the French actress Isabelle Huppert about her six years and nearly 100 performances as Mary Stuart in Robert Wilson’s Mary Said What She Said, say aloha to the the 2025 Hawai’i Triennial, celebrate architect Lina Ghotmeh’s British Museum win, and more.

Good morning!

I don’t think I’ve ever written about theater in this newsletter, but this week I have very good reason to. Last Sunday, I witnessed one of the more extraordinary live performances I’ve ever seen, and not just in theater. Isabelle Huppert, known for her complex and exacting roles as austere, mysterious women in films such as La Séparation (1994), The Piano Teacher (2001), and I Heart Huckabees (2004), played Mary, Queen of Scots in Mary Said What She Said, directed by the theater and stage director Robert Wilson (the guest on Ep. 96 of Time Sensitive) and one of our “Three Things” picks in our Feb. 22 newsletter.

In our “Interview With” featuring Huppert below, I write in more detail about the play—if one can even call it that; it’s an astounding 90-minute monologue—but suffice it to say that Mary Said What She Said is, both for Huppert and Wilson, a magnum opus. Perhaps not surprisingly, David Byrne, Hillary Clinton, and Cindy Sherman were among those in the audience on Sunday. Although it was in the U.S., at N.Y.U.’s Skirball Center, for just five days of performances, there will be the opportunity—for the especially adventurous, anyway—to see it this fall when it travels to Asia.

By chance, also this week, I went to see Othello on Broadway, starring Denzel Washington and Jake Gyllenhaal, another extraordinary production, if decidedly more classical and standard in form. Washington delivers a profound, career-apex performance as Othello, while Gyllenhaal is a fitting, if sometimes too audience-pandering, foil in Iago. I found Molly Osborne’s Desdemona to be a weak point—she just doesn’t seem to live the character the way Washington and Gyllenhaal do theirs—but this otherwise masterly modern-day take on Shakespeare sings. The exquisite ancient Venice-meets-Brutalist set design by Derek McLane makes for a flawless backdrop, too.

Before I finish, a quick housekeeping note: After our annual January-February pause of Time Sensitive, we’ll be returning with Season 11 of the podcast on March 19. For now, I won’t reveal which guests are behind the curtain (sorry, I can’t help it with the bad puns, and I do actually reveal one of them in “Five Links” below), but what I can say is that, interestingly, this season’s lineup is so far entirely international, with the guests we’ve recorded hailing not from New York but from London, Kyoto, Rome, and Paris, each of whom came through our Brooklyn studio.

—Spencer

“Boredom and laziness are very important elements of life. How are you ever going to know something new, or imagine something new, or feel something new if you keep yourself busy all the time?”

From the archive: Listen to Ep. 118 with the artist Francesco Clemente, recorded in our New York City studio on August 9, 2024, at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

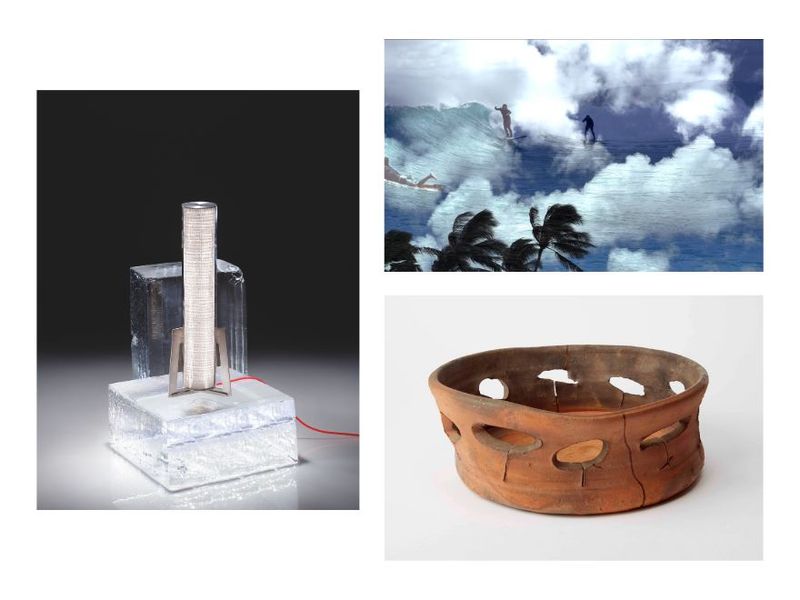

Artemide’s Criosfera light by Giulia Foscari

A previous collaborator of Rem Koolhaas’s firm, OMA, and Zaha Hadid, the architect Giulia Foscari is no stranger to highly conceptual thinking. As the founder of the Venice-based studio and “nonprofit agency for change” UNA / UNLESS, her latest design is not a building but a lamp: Criosfera, a floor or table model from the Italian lighting company Artemide that, Foscari tells us, serves as a “quintessential marker of our changing climate.” The lamp’s materials come from layers of blown recycled glass that introduce irregularity and craftsmanship, and its design is a reference to the earth’s frozen components—the cryosphere—most of which are found in Antarctica, where the icy layers hold a tremendous amount of data on the planet and its climate history. Foscari, an expert on this topic, edited the 2021 book Antarctic Resolution (Lars Müller Publishers), a volume of writing focused on the region and the notion of the Antarctic as a “global commons.” Intended to highlight our “spiraling environmental crisis,” she says, Criosfera “projects an unwavering optimism that we will, individually and collectively, act in defense of intergenerational justice.”

Hawai‘i Triennial

This year’s Hawai‘i Triennial, themed “Aloha Nō” and curated by Wassan Al-Khudhairi, Binna Choi, and Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu, serves as a way to recapture the truest meaning of the island greeting. On view through May, the triennial’s fourth iteration features works that embody rebirth, resilience, and resistance by 49 internationally renowned artists, including Teresita Fernández (the guest on Ep. 5 of Time Sensitive), Kapwani Kiwanga, and Rose B. Simpson, as well as local Hawaiian talents such as the poet Brandy Nālani McDougall, the painter Carl F.K. Pao, and the filmmaker Sancia Miala Shiba Nash. “Aloha Nō” is a call to know the layered meaning (kaona) of aloha in all of its forms—land, people, place, healing, tradition—through activity and engagement, placing the audience in deep conversation with themselves and their surroundings.

“Wild Earth” at the Columbus Museum of Art

Putting into dialogue two artists whose mediums spring from the ground, Wild Earth: JB Blunk and Toshiko Takaezu at the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio is perfectly titled—and unmissable. Though the two never met, the museum is the first to ever pair JB Blunk (1926–2002) and Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011), and highlights through nearly 200 artworks their deep connections to their shared mentor, the Japanese master potter Kaneshige Tōyō; the Japanese Mingei movement, which celebrates the beauty of everyday objects; and nature. Curated by Daniel Marcus, the exhibition includes large-scale sculptures and wood carvings and small vessels and bowls created by the artists, and is a rich conversation on the enduring connection that art provides in life and death.

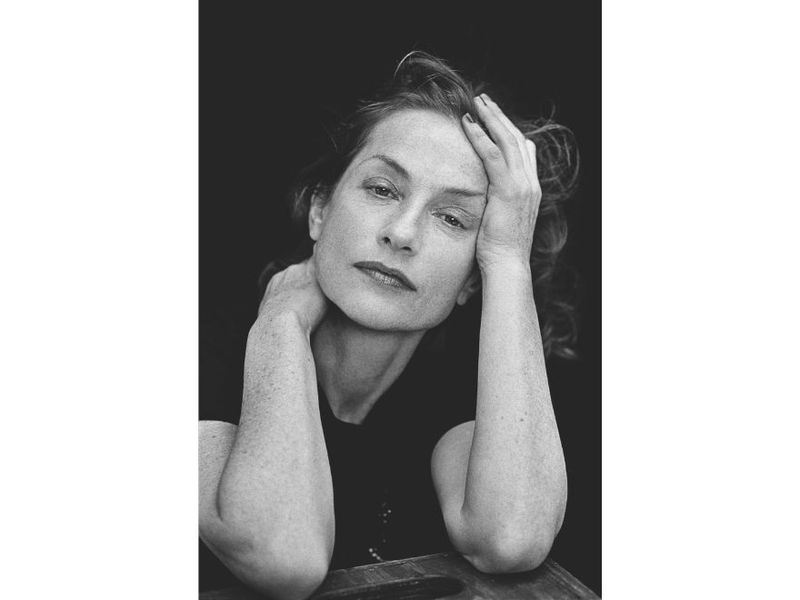

The French actress Isabelle Huppert has appeared in roughly 150 film and theater productions across her prolific and varied career, and her most recent one as of this writing, Mary Said What She Said—which she’s been performing in since 2019, when it debuted in Paris, and which just wrapped its U.S. premiere at N.Y.U.’s Skirball—may very well be among her most marvelous and astounding. An impassioned feat of endurance and agility, this 90-minute piece of experimental theater, directed by Robert Wilson, stars just Huppert, playing Mary, Queen of Scots, alone on the stage for its entire duration, speaking a nearly nonstop script by the novelist and playwright Darryl Pinckney. True to trademark Wilson form, the performance is a minimalist masterpiece combining contrasting speeds and tempos: Wearing a dress inspired from paintings of Mary Stuart, Huppert appears at times to barely move, her striking silhouette practically hovering in place, while at other times, she swiftly marches back and forth, waving her arms up and down; sometimes, she speaks so quickly—violently, almost, and in French (there are English subtitles)—that there’s barely any time to process her rapid-fire words, while other times she slows her speech to a more casual crawl. Wilson’s subtle use of light and the score by the Italian composer Ludovico Einaudi adds to the play’s pulsing rigor. The startling, hypnotizing result alchemizes Wilson’s and Huppert’s artistry to potent effect.

Last Sunday, just three hours before Huppert’s final Skirball performance, we met up with her at The Mercer hotel in downtown Manhattan to talk about what it’s been like to work on this extraordinary production.

You’ve had a long engagement with Mary, Queen of Scots. It’s almost been thirty years since your debut in Schiller’s Mary Stuart, at the National Theatre in London in 1996, and since 2019, you’ve been performing the role in Mary Said What She Said—first in Paris, then in Stockholm, London, and Korea, and now in New York.

Today is something like the ninety-ninth performance. Actually, we’ll be doing the hundredth this fall.

Tell me about this relationship you have with playing the role of Mary Stuart for so long.

It’s almost random. I never really ever dreamed of Mary Stuart. It was never my own impulse. But over the thirty years now, I’ve certainly built up an attachment to this woman. Although, to be quite honest, working with Bob Wilson never makes you elaborate a classical relationship to a character. Of course, I’m aware that I play Mary Stuart—lots of people walk out of the room saying that they’ve been very moved by her story. But I never speak with Bob in terms of character. We mostly never speak about the text itself, either, because as with all of Bob Wilson’s work, it’s so formal. It’s abstract. It doesn’t go through the classical kinds of devices—character psychology, emotions, feelings. At the end of the day, I think you get a lot of emotion, but it comes through another way—a side, mysterious way.

This might sound random, but I wanted to reference your role in the 1975 film Aloïse, in which you play a schizophrenic painter living in a mental institution who has dreams of becoming an actor and studying drama. There’s a moment in the film where she says, “I’m not scared of a big, empty stage.” Does that line ring true for you with this Mary Said What She Said performance?

I’ve always liked that line. She says, “I’m not scared by a big, empty stage. That’s not what I’m scared of.” Meaning, of course: I have lots of other reasons to be scared.

Actually, she [Aloïse Corbaz] was schizophrenic, and she spent thirty years of her life locked in a psychiatric hospital. I love this aesthetic movement built by Jean Dubuffet, who gave words and speech to people that were not socially admitted or considered. Now there’s this museum of art brut—that’s what the movement is called. It’s a beautiful museum in Lausanne, and I’m always very touched by seeing the works there. For instance, you have this wood wall of a jail cell that was sculpted with a spoon handle, year after year, by a prisoner [Clément Fraisse].

Well, I bring up that quote because I was thinking about what it must feel like for you to be on the stage, completely alone, for ninety minutes straight.

I was thinking about it yesterday. For a while, there was a lot of anxiety for me doing it, and now it’s getting.… It took time. The more it goes on, the more I really enjoy doing it. It’s a big run-through. You go through an experience, a long journey. I’m alone on stage, and it’s like the audience doesn’t exist. It’s a very intense feeling. In a show like this, there’s a strange connection with the audience. It’s not the usual connection. Usually, in a classical play, you have reactions from the audience. You tend to build a relationship with the audience. This is not really that.

Could you talk about the intensity of doing this play while also having so much other work going on?

This moment, I have to say, is quite intense. Recently, I had four plays touring at once. I’m saying four because the last touring play I did was The Glass Menagerie, directed by Ivo van Hove, which was in Beijing in December. And I’ll go back to China—to Macau, to Beijing, to Shanghai, and to Nanjing—in April to do The Cherry Orchard, staged by the great Portuguese director Tiago Rodrigues, who now runs the Avignon Festival. Meanwhile, I’m still touring Bérénice, which I’m doing with the director Romeo Castellucci, all over Europe.

So yeah, I jump from one piece to the other, but Mary Said What She Said, we last did it in Korea in October [before this run of performances in New York], and next we’ll be doing it back in Asia.

This is your third collaboration with Bob, following Orlando (1993) and Quartett (2009). How and when did the two of you first meet?

By pure chance. If I didn’t go out this one evening, I’m not sure I would have ever met Bob. He saw me unexpectedly, and after one hour of talking, we were having dinner together. He suddenly asked me if I would do Orlando in Paris, because he’d just done it in Berlin with Jutta Lampe, the great German actress. If it wasn’t for that evening, I’m not sure we would have considered doing a project together. I don’t think Bob goes with the usual process. The way things arise in his mind is very special. That evening, he said, “Don’t you want to do it?” I said yes, and that’s how the whole thing started.

It strikes me that, like Bob, who’s known for his rigorous productions that give viewers time and space to think, your acting similarly allows for multiple readings. What I’m talking about here, I suppose, is ambiguity and intentionally leaving room for interpretation. Do you see this connection between your work and his?

That’s what’s really fascinating about working with Bob, is that you couldn’t think of something more precise, abstract, formal. Bob is the emperor of formalism on stage. He invented a new language when he first appeared, working with rhythms that go from slow to very rapid. He plays with these contradictory rhythms. While the body language can be slow, the words will be very fast. The most fascinating thing about it is that, within this very formal and established thing, you have to put the entire figure in exactly the right place. The whole body, from the bottom of your feet to the tip of your finger—you have to keep that energy. I think you resent that energy. But within this, you couldn’t be more free.

Bob never gives me any indication. He’ll just say, “A little more interior.” That says it all. If he says that, you understand that you’re not supposed to look for the audience. Staying in your own body, that’s what gives the audience a feeling of mystery. You want to go to that interiority, whereas if you try to establish more contact with the audience, you break something. So that’s the only thing he’ll tell me. Or with vocal indications: “louder,” “slower,” “more interior.” That’s it, with no explanation. He says it’s like music or even painting: Why not put a little bit of red here and some blue there? Within that frame, I feel so free. I can be serious, I can be funny, I can be sad. I can be everything.

Tell me about the importance of listening in your work. You’ve previously said, “I don’t believe in the idea of playing a character. I just believe in the idea of playing states—joy, sadness, laughter, listening….” Could you share how listening comes alive in your acting?

I keep saying good actors are the ones who know how to listen. When an actor is not able to listen, it’s very annoying. It doesn’t establish a true connection. There should be as much listening as talking, receiving and expressing what you feel just by listening. Some actors don’t know how to listen or take their time.

Could you speak to the role of listening in Mary Said What She Said?

Well, in this piece, there’s more talking than listening. [Laughs] But I do listen to myself, because I am totally aware, and I have real pleasure saying the words in a certain way. Whether I speak very fast or very slow, I enjoy my own music. In a way, that’s also listening because I have no partner to listen to on stage other than myself.

This interview was conducted by Spencer Bailey. It has been condensed and edited.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

Doggerel, the latest book of poems by Reginald Dwayne Betts (the guest on Ep. 58 of Time Sensitive), released this week, is at once vulnerable, philosophical, playful, and richly layered [W.W. Norton]

The writer and activist Rebecca Solnit (the guest on the finale episode of our At a Distance podcast, which wrapped its three-year run in December 2023) recently launched a newsletter that stems from the vital belief that “even in an emergency, or rather especially in an emergency, meditation as gathering ourselves and deepening our understanding is exactly what we need to do” [Meditations in an Emergency]

The Lebanese-born, Paris-based architect Lina Ghotmeh (who’s an upcoming guest on Season 11 of Time Sensitive) won the competition to rethink and revamp the British Museum’s Western Range galleries—overhauling one third of the museum’s overall gallery space [The Art Newspaper]

The Pachinko author Min Jin Lee (the guest on Ep. 102 of Time Sensitive) selects four books that “explore the lives of 20th-century women weathering the consequences of the choice their families made to move from one place to another—books that are simultaneously intimate character studies and examinations of wider social transformations” [The New Yorker]

Two years in, a look at what residents of Culdesac Tempe, Arizona—America’s first “car-free neighborhood”—think of the “ambitious experiment,” and what it means for the future [Dwell]