In this week’s newsletter, we talk about mysticism with the philosopher Simon Critchley, stand in awe of Faye Toogood’s material intelligence, preview a Mathieu Lehanneur exhibition in Paris, and more.

Good morning, and happy new year! Sending love and prayers to our readers in Los Angeles. (Here’s how to help those affected.)

To kick off 2025, I thought we’d start with a bit of mysticism. Joining me for the occasion is our “philosopher-at-large,” the one and only Simon Critchley, whose brilliant new book is titled, yes, Mysticism. Below, you’ll find our conversation, which spans references to Canterbury Cathedral, Iggy and the Stooges, and Bob Dylan.

Reading Simon’s book and preparing for our conversation got me thinking about some of my own mystical moments. Like Simon, I’m certainly no mystic, but I have had sensations and experiences—flashes—that verge on the mystical.

In my youth in Colorado, I played ice hockey goalie on several teams, and I remember one game in particular, in Colorado Springs, when I looked up at the roof of the rink and sensed some sort of higher power above me. I completely stuffed the other team that day, leaving them goal-less and even having one standout moment that involved a dramatic pad-stack and puck-in-glove save that led one person in the stands to scream out, “Holy moly, what a goalie!” Perhaps it was just skill and luck, but something about that game felt mystic and spiritual—and almost religious, of a higher order, even “holy.”

Another instance, more recently, involved music—which is Critchley’s main realm of mysticism, if ever there was one. Two months ago, at the Grand Cube Osaka in Japan, my wife and I went to see Thom Yorke, of Radiohead fame, perform a solo set of songs from across his career. When he started playing “Unmade,” from the soundtrack to Luca Guadagnino’s 2018 film Suspiria, tears immediately began rolling down my cheeks. It was an entirely uncontrollable and overpowering moment of what the psychology professor Dacher Keltner would call awe. For days after, I felt unmade (in a good way!) by “Unmade.” That song and that concert pulled me out of myself not only in that moment, but for days and weeks following. If mysticism is, in part, the act of letting go, then what I experienced was certainly mystical. (That Osaka show followed Thom Yorke performances I’d seen in Sicily, in 2023, with his band The Smile, and in Brooklyn, in 2018, that were similarly awe-filled and also, in some sense, mystical.)

I can think of many mystical art and architecture experiences, as well: at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City, Queens; at the Noguchi Museum in Takamatsu, Japan; at the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver; at the Chichu Art Museum in Naoshima, Japan; at the Matisse Chapel in Vence, France…. I could go on.

At its absolute best and most refined, food has also had such a power over me. Last year, a birthday dinner at House Brooklyn left me buzzing for days. Both times I’ve eaten at René Redzepi’s Noma in Copenhagen—first in 2017 and then again in 2019—I left practically floating out of the restaurant. These experiences were more than just exquisite; they were transcendent.

We live in trying, often bleak times. But I think we can counter some of the world’s pressure-cooker weight by actively seeking out more mystical moments. More moments of beauty and awe and surprise and ecstasy. These heightened feelings often arrive when we least expect them, but it takes being open—being on a “journey,” basically—to find them in the first place. And sure, some of what I’m writing here might be magical thinking. But what’s wrong with that? I wish for you all to encounter many similarly elevated experiences in the year ahead.

—Spencer

“Everyone has a different strategy for managing the kind of inevitable anxieties that come from being a human being. Mine is just not to live in the future.”

Listen to Ep. 125 with Malcolm Gladwell at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

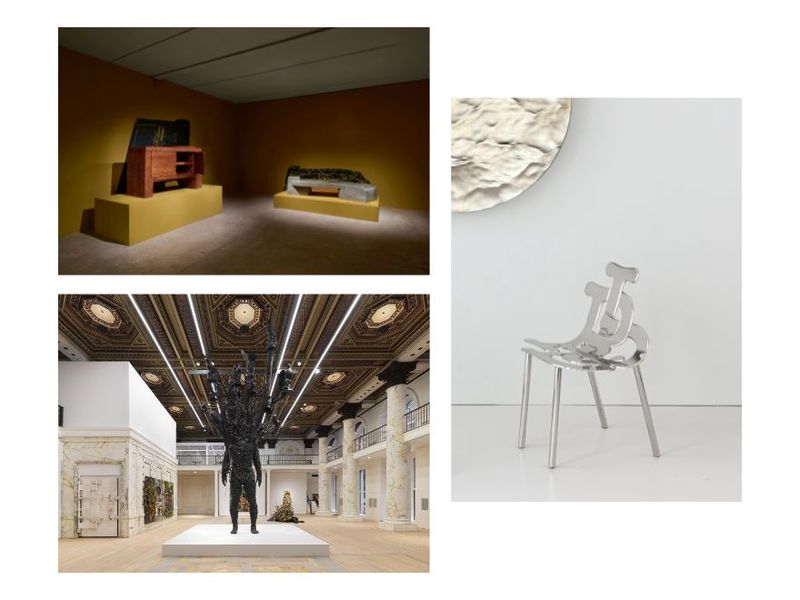

“Assemblage 7: Lost and Found II” at Friedman Benda

Two specific materials—English oak and Purbeck marble—are the focus of “Assemblage 7: Lost and Found II,” the British designer Faye Toogood’s just-opened exhibition at Friedman Benda gallery in New York (on view through March 15). Expanding out of a presentation that was first previewed in Los Angeles in 2022 and then in the U.K. in 2023, “Assemblage 7” serves as a meditation on what is lost, reworked, and reclaimed. Quintessential ingredients of British craftsmanship throughout history, both oak—a mainstay building material finished by shellacking, a fine-furniture technique dating back to the 18th century—and Purbeck, a rare limestone packed with fossils that was often used as cathedral cladding in medieval times, draw on the nation’s traditional artisanal vernacular. Carving these materials, Toogood says, felt “like an archaeological dig: The block was a landscape, and I was finding my treasure within this block.” Each piece—“Plot,” “Cairn,” “Barrow,” “Hill,” “Hoard,” and “Lode”—displays elements that had long been hidden, or, in the words of Toogood (who will be a guest on our next season of Time Sensitive, running from March through June), “something almost prehistoric that had been lost to time.”

“Ici et Maintenant” at Christie’s France

Following the success of the French designer Mathieu Lehanneur’s 2018 exhibition “50 Seas”—a project that catalogued the colors of the seas and oceans in a series of ceramic wall sculptures—the renowned auction house Christie’s is welcoming him back for a second presentation with a series of new works. Titled “Ici et Maintenant,” which translates to “Here and Now,” the exhibition (on view from Jan. 17–23) explores the concepts of nature, time, and individuality. With his collection “I Am,” Lehanneur has created a series of made-to-order chairs, shaped in aluminum, then finished with a nickel or copper plating, each a one-of-a-kind piece crafted in the shape of the initials of the person to whom it is dedicated. To mark the launch of the collection, the artist has created 12 models inspired by icons ranging from the architect and inventor Buckminster Fuller to the late record producer and composer Quincy Jones to Marie Curie. “Our initials are our first DNA—our genealogical and symbolic code,” Lehannaur says. “I wanted to create an emblem for each of us.” Another installation, a floating metallic balloon, will commemorate the Olympic cauldron Lehanneur designed that flew across the Paris sky last summer.

“Nick Cave: Amalgams and Graphts” at Jack Shainman Gallery

The artist Nick Cave (the guest on Ep. 86 of Time Sensitive) is perhaps best known for his series of more than 500 Soundsuits—eccentric, sculptural forms that camouflage the body, thereby concealing race, gender, and class, and forcing observers to see the wearer without prejudice. Presented by Jack Shainman Gallery as the inaugural show at its new flagship Tribeca location, “Nick Cave: Amalgams and Graphts” (on view through March 15) introduces two distinct series that push the artist’s singular vision into a new, nature-forward realm. Anchoring the exhibition is a series of three large bronze sculptures, titled “Amalgams,” that evolved out of the Soundsuits series, fusing casts of Cave’s own body with natural forms such as flowers, birds, and trees to similar effect. Debuting alongside these bronze figures is Cave’s newest series, “Graphts.” These mixed-media assemblages situate needlepoint self-portraits of the artist among fields of florals and color constructed from vintage serving trays. As a whole, the presentation revolves around the meaning of self-portraiture, inviting collective introspection about the formation of our own selves and how they relate to both beauty and the sinister forces all around us.

“Reality presses in on us from all sides with a relentless force, a violence, which drains our energy and dissipates our capacity for belief and for joy,” writes the philosopher Simon Critchley in his highly engaging—and, in various fiery moments, transcendent—new book, Mysticism (The New York Review of Books). “The world deafens us with its noise; our eyes sting from the ever-enlarging incoherence of information and disinformation and the constant presence of war. We all feel, we all live, within the poverty of contemporary experience. This is a leaden time, a heavy time, a time of dearth. As a result, we feel miserable, anxious, wretched, bored.” Expanding out from this dim reality, zeroing in on the term, and extrapolating it in various directions, Mysticism—which follows titles by Critchley on subjects ranging from Greek tragedy to David Bowie—is a beautifully wrought book about trying to get outside of oneself through some sort of higher power, whatever that may be. Here, we sit down with the author, whom The Slowdown happily claims as our “philosopher-at-large,” to talk about the subject and the book.

You open with the line “Once upon a time, there was a plague,” and go on to connect mysticism with “extreme experiences of doubt, dereliction, dreams, hypochondria, and hallucination.” In some ways, this book came out of Covid. Did the pandemic awaken mysticism in you?

Yes, in me and many others. We retreated into ourselves. We suffered serious disorders and had a powerful desire for connection, for love. A pandemic awakens something archaic, something very old, in us. We realize that we’re part of a long line of civilizations that have been defined by a plague, even though we think we’re in this modern, contemporary world.

That was the context, but the work goes back earlier. The pandemic just focused it, realizing what people were going through, the kind of yearning they had—which was also, in part, religious.

When did you first get a sense for mysticism?

Through reading. I’m not a mystic. I’ve only had one or two flashes, as most people do, often in relation to nature.

What’s one mystical flash that comes to mind for you?

When I was in Canterbury Cathedral. I’d been studying medieval literature and Gothic architecture, so I knew in the context, I understood the rational coherence of the cathedral as a visual symbolic display. But then I began to understand it as a place of devotion. I remember feeling just this sense of awe and majesty—and then I felt bad about it, because it felt like a fraudulent experience. I wasn’t really having a religious experience.

You beautifully lay out a number of definitions of mysticism in the book. What’s your personal favorite?

“Experience in its most intense form.” You’ve actually left yourself for a moment, however that might happen. For me, it happens most often with music. You have a couple of drinks, you put on that track by Iggy and the Stooges, and you’re there. There is a God at that point, and he’s a 70-year-old man from Detroit with a very questionable history of substance abuse. [Laughs]

Connected to music, you write about breath as “the original form of ‘spirit,’” noting, “The philosopher’s ‘I think therefore I am” might be more properly conceived as ‘I breathe and thus it is.’” I feel like I’ve been practicing the latter perspective my whole life!

In Descartes’s “I think, therefore I am,” it’s all your cognitive awareness. You’re locked in your consciousness, whatever that is. With breath, you’re connected. Breath is inside you and outside you. It’s a kind of prayer, breath. Every exhalation, every inhalation, is a kind of inspiration and a lesson. If we think about breathing as what we’re doing—that it’s who we are—then we don’t think of ourselves as prisoners of our heads.

You point out that to be a writer is a form of mysticism. There is a mysticism embedded in the act of writing.

Yeah. I write about Annie Dillard, and she talks about being in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. She’s got a campfire going. She’s trying to remember why she wanted to become a writer in the first place, and she’s got this book on the French poet Rimbaud and what it was that set Rimbaud “on fire” during the brief number of years he was a poet—before he became a dirty colonial trader and whatever else he did. This moth goes into her campfire and catches fire, dies, and then lights up. She sees that, watches it, and then she uses that light to read the book. Her point is that all a writer can do is be the possibility of a flame, and when you’re on fire—or when you become a flame for other people to read by—the identity of the writer is of no consequence at all. When you’re looking at the flame, you’re not looking at the wick.

The great mistake we make with writers and with artists is that we confuse the flame with them. Most writers and artists are uninteresting. What’s going on through their heads is as boring as what’s going on through our heads. But there are certain people that can set themselves alight. Then you can watch that. But it’s the flame you’re looking at, and not them. Then we make biopics about them.

Bob Dylan.

Bob Dylan! Bob Dylan has no interest in himself. He has no interest in Bob Dylan. That’s why he’s told lies about himself since 1961—that he was, you know, in the carnival for six years. But the point is, he’s trying to say, “Listen to the song. Listen to the music.” Who Bob Dylan is, that’s of no consequence, especially to Bob Dylan. The paradox of that is that people then just become interested in Bob Dylan. So you can’t stop it.

Scorsese gets it right in his film Rolling Thunder Revue. He takes the premise of the fiction that is Bob Dylan and magnifies that, blurs facts and fiction. That’s more Dylanesque, it seems to me, than the new biopic with Timothée Chalamet.

Who’s your favorite mystic from across time?

Julian of Norwich, the first woman to write a book in English. There are canons of English literature, and where do you begin? People begin with Langland and Chaucer. They should begin with Julian of Norwich. She was writing in an urban context, in a time of plague. She had no education, so was an informal theologian, and she basically reinvented Christianity on her own. It’s an extraordinary achievement. In 1373, she experienced these strange “showings,” as she called them, for about twelve or thirteen hours, and then she spent the next forty years figuring out what they meant—and their meaning was love. That’s the conclusion.

From the past fifty years or so, who would be your top mystic?

Nick Cave. [Editor’s note: Critchley’s referring to the Australian musician, not the Chicago-based artist mentioned above in Three Things.] He’s an obvious candidate. He has come to embrace Christianity in very direct ways. I met him on June first last year, and we exchanged email addresses. I saw his Gmail account, and the top message on it was from Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury. I said, “Rowan fucking Williams?!” He said, “Yeah, he’s my mate.” For Nick Cave, mysticism is something that has happened through grief. Two of his sons have died in the last eight, nine years, and he and his wife have suffered greatly. I think it’s led them to surrender, to work their pain into something else.

Also, his concerts are religious. They’re communions.

Did writing this book bring you closer to God somehow?

It brought me as close to God as I’m gonna get, which is like having my nose pressed against the glass. If I’m still looking through the window, I want to get into the store and eat all the candy and drink all the root beer. But I still feel like a fraud in that sense.

This conversation took place at Montague Diner in Brooklyn Heights. It has been condensed and edited.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

For a long, slow read to settle in to the new year with, may we humbly recommend this masterful Caitlin Flanagan cover story, a deeply personal paean to the late Irish poet Seamus Heaney [The Atlantic]

Ruthie Rogers, chef-owner of London’s River Café (and the guest on Ep. 85 of Time Sensitive), shares a few of her favorite restaurants, including Chez L’ami Louis in Paris, Contramar in Mexico City, and Dar Yacout in Marrakech [Condé Nast Traveler]

A strange, rather unexpected mash-up that we happily welcome: The lyrics for the latest single from Dirty Projectors come from the opening paragraph of The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells (the guest on Ep. 56 of Time Sensitive) [YouTube]

Architectural Digest’s Sam Cochran gets a first-look preview of the new Frick Collection building, sensitively updated by architect Annabelle Selldorf (the guest on Ep. 104 of Time Sensitive, who also joined us for a live talk in New York City last fall) and scheduled to open in April [AD]

Simon Critchley—interviewed above (and the guest on Ep. 42 of Time Sensitive)—delves all the deeper into the subject of mysticism on writer Sean Illing’s The Gray Area podcast [Vox]