In this week’s newsletter, we speak with architect Elizabeth Diller about her boundary-pushing firm’s first-ever monograph, preview Kim Hastreiter’s kaleidoscopic “My Amazing Friends” exhibition at Jeffrey Deitch, and more.

Good morning!

Putting together this week’s newsletter got me thinking about when the work of the architecture firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro first came on my radar. I’m guessing, as was the case for so many of us, it was via the High Line. That catalyzing project redefined not just public space in New York City, but urban planning globally, spawning copycats galore. It quickly became difficult for anyone to not know about it. Soon enough—and this remains the case today—roughly eight million people were walking up and down it each year.

If there was one word to define the multifaceted practice of DS+R—led by partners Elizabeth Diller (the guest on Ep. 9 of Time Sensitive), Ricardo Scofidio, Charles Renfro, and Benjamin Gilmartin—for me, it would be performance. This is probably because one of the most remarkable performances I’ve ever seen, the Mile-Long Opera (2018), was co-created by DS+R and the Pulitzer Prize–winning composer David Lang on—where else?—the High Line. A reflection on the “changing meaning” of 7 p.m., the performance’s start time, it featured singers stationed all along the 30-block-long park. The city beyond became its own sort of stage. Time slowed. A humming, whirring sense of serenity took over. I was in complete and utter awe.

Notions of performance can also be seen in the firm’s Blur Building (2002), a temporary structure constructed on on Lake Neuchâtel for the Swiss National Exposition that pumped water up and shot mist through high-pressure nozzles to create a “façade” of fog; or in the porous concrete skin of the Broad museum (2015) in Los Angeles; or at The Shed (2019), its shell itself a literal architectural performance, able to move back and forth on enormous steel wheels.

A sense of stultifying sameness and dulling global uniformity has been speedily taking over cities around the world the past two decades, but DS+R is among a small but essential cadre of high-profile firms that consistently fight the good fight in the face of this, creating evocative architecture that invites wonder, exploration, and curiosity. Sometimes, DS+R’s work has been met with controversy, as with the Museum of Modern Art renovation and expansion in 2019, which resulted in the demolition of Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s jewel-like American Folk Art Museum building (2001). But that moment, firestorm that it was, reads as a relative blip in the firm’s remarkable output. Across its 40-plus-year trajectory, DS+R can certainly be credited for staying true to its artistic principles, managing to hold onto its avant-garde roots even while becoming, at least in an architecture-industry sense, “mainstream.”

In this week’s newsletter, our editorial assistant, Emma Leigh Macdonald, speaks with Liz about the firm’s latest project, a form-defying monograph from Phaidon that offers multiple ways into DS+R’s pioneering practice. I hope you enjoy their conversation as much as I did.

—Spencer

“You don’t meet many people with wisdom. You meet a lot of people with opinions.”

From the archive: Listen to Ep. 65 with Bethann Hardison, recorded in our New York City studio on April 12, 2022, at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

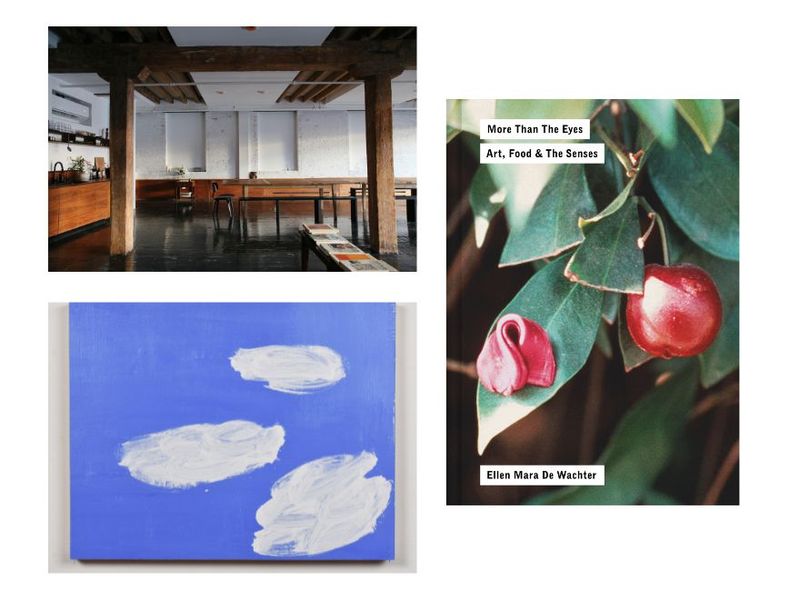

Bon Studio

While one would never guess it upon first glance, Williamsburg’s newly formed Bon Studio—a minimalist space built around design, food, and community—came to fruition in only six weeks. Before finding the promising listing for the space on Craigslist, co-founder Anabelle Cole wasn’t even sure she’d be moving to New York City. She and photographer Samantha Hillman came across the vacant loft when she was in town visiting and considering leaving Los Angeles, where she’d created the much-loved Apta event space in Echo Park. The available listing, coupled with her and Hillman’s shared vision, became her sign to take the leap. “I’ve been wanting to create a space that’s not just based on product—and is as far away from members-only as possible,” she says. To start, the pair will host dinners and various events, also showcasing a tightly curated collection of rare books and craft objects, with the aim of making Bon Studio a platform for community and connection. Their approach to the interior of the sun-drenched space could certainly be described as wabi-sabi, but even more refreshing, so can their programming.

More Than the Eyes: Art, Food & the Senses (Atelier Éditions)

As a universally relatable medium, food has been a subject of artistic practice since berries were first used for paint, and much discussed in recent years as a tool for social commentary itself. As author Ellen Mara De Wachter puts it in the introduction to the just-released More Than the Eyes: Art, Food & The Senses (Atelier Éditions and D.A.P.), “If you want to bring up difficult issues, involve food. If you want to know what’s going on in a culture, look at what is happening with food.” In her beautiful, highly stimulating new book, De Wachter explores artistic food interventions in works by artists such as Agnes Denes, Sarah Lucas, Carolee Schneemann, and Andy Warhol, delving into their oeuvres through the angle of food. Ultimately, De Wachter makes the case that, in a world where sight is prioritized above our other senses, it’s innately expansive, enlivening, and mind-expanding to work with mediums that can also be smelled, tasted, and touched.

“My Amazing Friends” at Jeffrey Deitch

In the lead-up to the release of the forthcoming book Stuff: A New York Life of Cultural Chaos (Damiani), by downtown-culture doyenne and Paper magazine co-founder Kim Hastreiter (the guest on Ep. 18 of Time Sensitive), the art dealer Jeffrey Deitch is bringing the publication to life in exhibition form at his 76 Grand Street space. For the show, “My Amazing Friends” (opening tonight and on view through February 22), Hastreiter asked more than 60 of her nearest and dearest who are included in the book to submit a work of art that they know she loves. Fittingly, Deitch and Hastreiter are longtime pals, too, and have been collaborating with each other on various projects for 25 years. The resulting assemblage, curated by Hastreiter, is at once extremely off the wall (both literally and figuratively) and very personal, and includes works by the artist Marilyn Minter (the guest on Ep. 90 of Time Sensitive), the painter Francesco Clemente (the guest on Ep. 118), and Michael Stipe, with the contributors, notably, ranging in age from 27 to 87 years old.

A classic trope of the architecture book is to attempt to turn it into an architectural project in and of itself. Almost always, these efforts fail: Books are not buildings. The just-released, years-in-the-making Architecture, Not Architecture (Phaidon), however, succeeds where so many other experimental monographs like it have failed. Perhaps it comes as no surprise, then, to learn that the firm behind it is the New York–based practice Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Conceived as a “portable archive,” the two-book publication puts the studio’s built projects and more conceptual works in dialogue via a choose-your-own-adventure design that guides readers through a multitude of possible connections spanning the course of DS+R’s 40-plus-decade long journey. Here, founding partner Elizabeth Diller tells us how her affinity for photography and film influenced the project, and what medium might be next now that “monograph” has been checked off the list.

Why did you decide to make this book now? How did the publication come about?

We love books, and we love making books as another manifestation of a project. Books are always spatial artifacts for us; we’re control freaks, and we like to design them ourselves. We’ve made books for particular projects—one of Blur, one of Lincoln Center, one of the High Line. They’ve been focused on a single project, and I think we just realized that’s inconvenient. [Laughs] The ambition was to make it a project in and of itself, and to make it more of a portable archive than a monograph, and within that, to identify two tracks within our practice: the architectural work and then performance, installations, objects, curatorial projects, and so forth.

Tell me about the process of designing the physical book itself.

Even though it’s anatomically separated into two volumes, there’s a connection. People have asked: Why would you separate them? The answer is, we tried to organize them in various ways—through chronology or geography. But it just made a mess out of everything, and you couldn’t actually understand the connections between things. We found with this structure of the book—sending the reader bouncing between each side—you’re really able to understand the interrelationships.

There’s something quite cinematic about the book. It basically opens up to become two “screens.”

Maybe that’s because there’s no linear way to go through it—you have not a table of contents, but tables of contents. You can find a project alphabetically, or chronologically, or by typology, or by obsession, which is one of the categories. You can follow an obsession to page three hundred on the other side of the book, for example. It’s like windows or links on a website that you can follow in many different directions.

This being the first publication to cover the full breadth of the practice, I’m curious how you view your work across time. What do you see as the biggest tipping points in DS+R’s practice, now that you’ve had the chance to look at them in hindsight?

I think there are tipping points that become more clear in the book, but there are also other surprises that we didn’t expect—like relationships or subconscious links between projects. It’s been a way to better understand certain trajectories. As for tipping points, I would say that Slow House, in 1991, was when we realized that we could actually build an idea. Then I would say the Blur Building, in 2002, is when we realized that our audience was not just people in the architecture world, that there is a broader appeal for what we do. There are others that gave us a certain legitimacy, and that showed us that we could be the ones to put something on the table—that you don’t always have to wait to be asked.

How did you decide on the book’s contributors? Edmund de Waal [the guest on Ep. 98 of Time Sensitive], Alan Cumming, and William Forsythe stood out to me in particular.

You know, I’m not really sure how we decided. Ideas came from all four of us. We looked at who knows our work really well. We decided not to have a historian or theorist validate our work with an introduction—we just wanted to introduce spirited dialogues, shed some insight, and make it a two-way conversation.

When you were a guest on Time Sensitive, you spoke with Spencer about finding architecture through photography and film. Now that you’ve done a book, do you see a documentary feature film in your future?

Oh, my God, my dream project! [Laughs] Well, right now we’re working on a six-channel video for the Venice Architecture Biennale, which is in parallel to a project at the V&A Museum about how our lives are all about storage. We’re also doing something for the Milan Triennial that’s about obsessive-compulsive cleaning. We do use the medium—time-based media—all the time. But to do a full narrative work and take up two hours of someone’s time, that takes a lot of skill. I hope one day to do it.

This interview was conducted by Emma Leigh Macdonald. It has been condensed and edited.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

Artist José Parlà (the guest on Ep. 95 of Time Sensitive) is hosting one-night-only “multidimensional” house party at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Feb. 22 [BAM]

Ian Parker’s epic, highly entertaining, 15,000-plus-word Norman Foster profile has us laughing, clapping, and cringing [The New Yorker]

Chef Yann Nury, who makes a mean chicken stock, shares his secrets around this “forgotten skill” [T Magazine]

Sensing a profound social media “sea change,” writer and cultural commentator Anne Helen Peterson asks, “What happens when the thing that structured so much of our lives loses its utility?” [Culture Study]

Stanford psychiatry professor and Dopamine Nation author Dr. Anna Lembke talks with great nuance and acuity about how, personally and societally, we might get out of the technology-fueled dopamine doom loops we so often find ourselves in [The New York Times]