The Cosmovision of the Yanomami People and the Violent Forces That Threaten Them

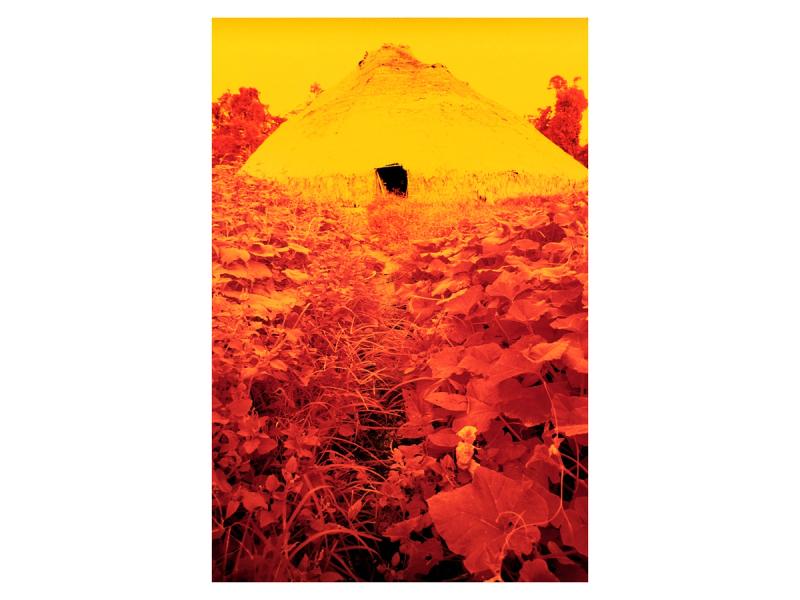

Entering “The Yanomami Struggle” exhibition at The Shed in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards, I find myself standing before a vast arrangement of photographs, some crisp and hyperpigmented, others blurred and grayscale, all suspended from the ceiling as if parts of a room-size mobile. After a moment of taking in my new environs, the subjects of the closest set of imagery come into focus. To my left is a diptych of a lake overcast by a stormy sky and a boy floating face up along a cerulean-blue river. To my right is a black-and-white collage of children traipsing across a rainforest floor. Directly ahead of me is the most arresting photo of them all: a lush canopy of trees, all a psychedelic fuschia, with a thatch-roofed hut inlaid therein. The flourishing scenes before me are a far cry from the barren, wintery stretch of the High Line I’ve just walked along to get here. I’ve somehow traversed a portal, and have arrived in another world.

This world is that of the Yanomami, one of the largest Indigenous groups living in Amazonia today. Estimated to have originated some 15,000 years ago and now composed of 35,000 people living in more than 200 villages, the Yanomami reside in the largest forested Indigenous territory on earth, an area of 220,000 square kilometers along the Venezuelan-Brazilian border. Not unlike other Indigenous peoples around the world, the Yanomami have, in recent decades—with the escalation of mining, deforestation, and the climate crisis—faced mounting threats to and extreme violence against their land, health, way of life, and existence altogether.

The group first came into sustained contact with outsiders in the 1940s, when the Brazilian government deployed teams to delimit the country’s frontier with Venezuela, leading to epidemics of measles and flu throughout the territory. Since then, Brazil’s military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985 and the illegal invasion of tens of thousands of gold miners from the 1980s onward have ushered in unthinkable devastation, including further spread of disease, the destruction of villages, and outright genocide. Gold mining and its associated harms alone killed twenty percent of the Yanomami population in its first seven years, and continues in the region to this day with little attention or action from the authorities.

Born in Switzerland and raised in Transylvania, where she escaped the Holocaust and moved to the U.S. in 1946, Brazilian artist Claudia Andujar has long stood as one of the most prominent allies of and advocates for the Yanomami. In 1955, Andujar moved from New York to Brazil, and began her career as a photographer, dedicating her practice to bringing attention to vulnerable communities. She first traveled to the Yanomami region in 1971 on assignment for the Brazilian magazine Realidade, sparking a lifelong relationship and a new focus for her art. Central to her relationship with the group is her friendship with Yanomami leader and spokesperson Davi Kopenawa since the 1980s. Over the years, together with other activists and organizations, Andujar and Kopenawa have worked with the Yanomami people and leaders against the invasion of Yanomami land, a fight that—beginning with Andujar and other activists’ creation of the Commission for the Demarcation of the Yanomami Park (CCPY) in 1978—led to the monumental 1992 demarcation of a continuous Yanomami territory by the Brazilian government. Andujar considers the fight a lifelong commitment: At 91, she continues working to protect the Yanomami and their rainforest homeland.

The first major retrospective dedicated to this five-decade-long collaboration between Andujar and the Yanomami, “The Yanomami Struggle” recently arrived at The Shed, where it’s on view through April 16, following presentations at the Instituto Moreira Salles in São Paulo, the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, and the Barbican Centre in London. The iteration at The Shed—organized by the Instituto Moreira Salles, Fondation Cartier, and The Shed in partnership with the Brazilian NGOs Hutukara Associação Yanomami and Instituto Socioambiental—is the most expansive yet. In addition to the more than 200 photographs by Andujar, the show has evolved to include more than 80 drawings and paintings by Yanomami artists, as well as video works by Yanomami filmmakers. The intention here, says Thyago Nogueira, the show’s curator, is to shed light on the activism being pioneered by the current generation of Yanomami (who were not yet active while Claudia was in the region), as well as to embolden the Yanomami as protagonists in their own fight. “Claudia and Davi were fighting for the Yanomami to have the possibility of expressing themselves, for themselves, by themselves,” says Nogueira. “These new artworks are part of that accomplishment.”

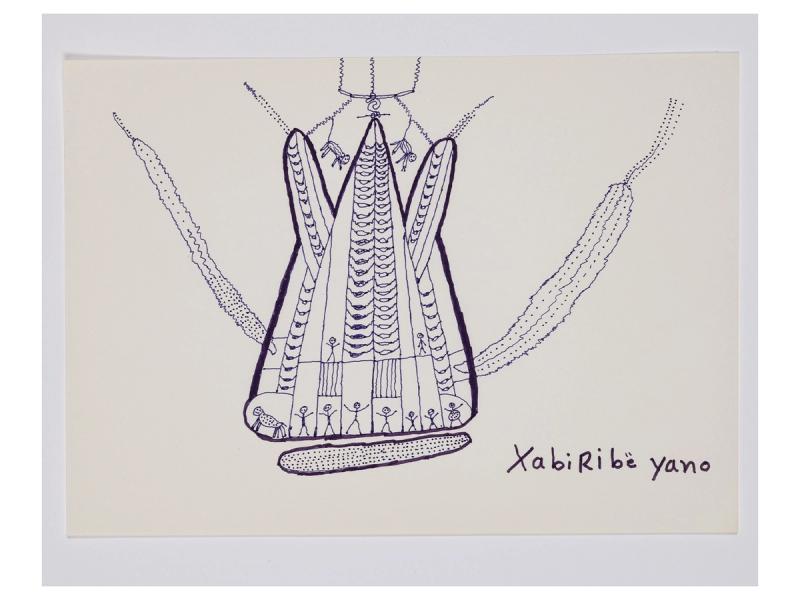

The exhibition is divided into two parts. The first, which populates the large entrance room, serves as a window into Yanomami life—their culture, traditions, and cosmovision, or physical and spiritual worldview—through what Nogueira calls “a forest of [hanging] images” of Andujar’s photographic work from the 1970s and accompanying words by Kopenawa, as well as drawings and films by the Yanomami artists. One black-and-white photograph by Andujar shows a group of Yanomami of all ages, spears and axes in tow, preparing for a hunting expedition. Another depicts two Yanomami women weaving baskets from palm fronds for the transportation of freshly caught game. Images captured inside the yano, the collective houses of the Yanomami, uncover the intimacies of everyday life, such as a boy lying in a barkcloth hammock, a man fueling a fire with his breath, and a woman painting herself with annatto dye and genipap (a fruit native to Amazonia) with the assistance of a handheld mirror. Throughout, the words of Kopenawa smooth and shape the viewer’s experience, making clear the profound love and reverence the Yanomami have for their forest home. “The forest belongs to Omama (the Yanomami creator deity),” reads an image caption by Kopenawa. “If it is not destroyed the forest never dies. It is not like humans’ bodies. It does not rot and disappear. It always becomes new again.… The forest breathes but the white people do not notice. They do not think that it is alive.”

Early on in her relationship with the Yanomami, Andujar began experimenting with various photographic techniques: applying petroleum jelly to the camera lens to create a smudge or blur effect, using infrared film, or re-photographing her own images through colored filters. Because of this—despite the relatively quotidian nature of the activities pictured—Andujar’s photographs emanate an uncanny surrealism, communicating to the viewer a palpable energy more than merely a scene. Resisting stillness, they assume a filmic quality that translates the invisible elements of the Yanomami culture and worldview in a way that traditional images would fail to grasp.

These otherworldly qualities are particularly essential given the threads of Yanomami spirituality—which revolves around xapiri, or shamanic spirits—woven into nearly all of the scenes depicted. “In the photos,” reads a segment of the wall text, “a worn-out roof made of palm leaves seems to glitter like a starry night sky; a young man by the fire resembles an ancestral deity enveloped in smoke; and a curious child embraced by sunlight glows like a spiritual being.”

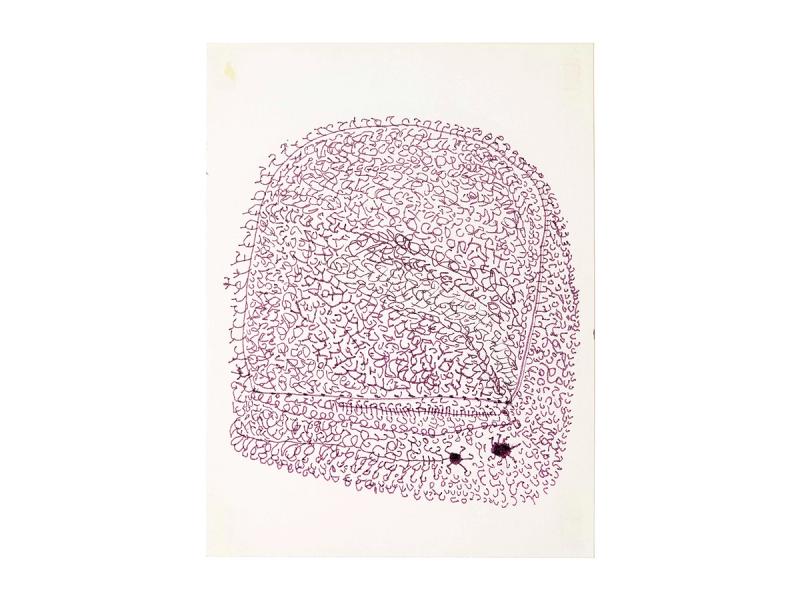

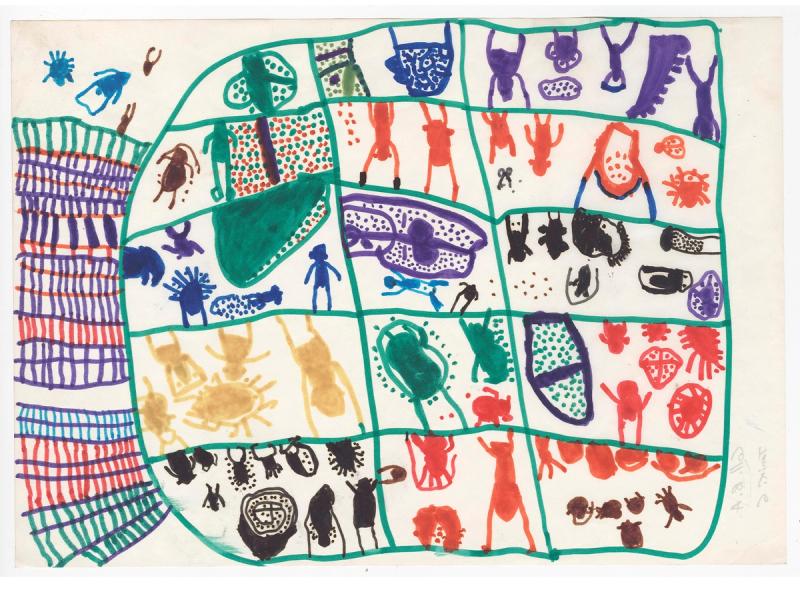

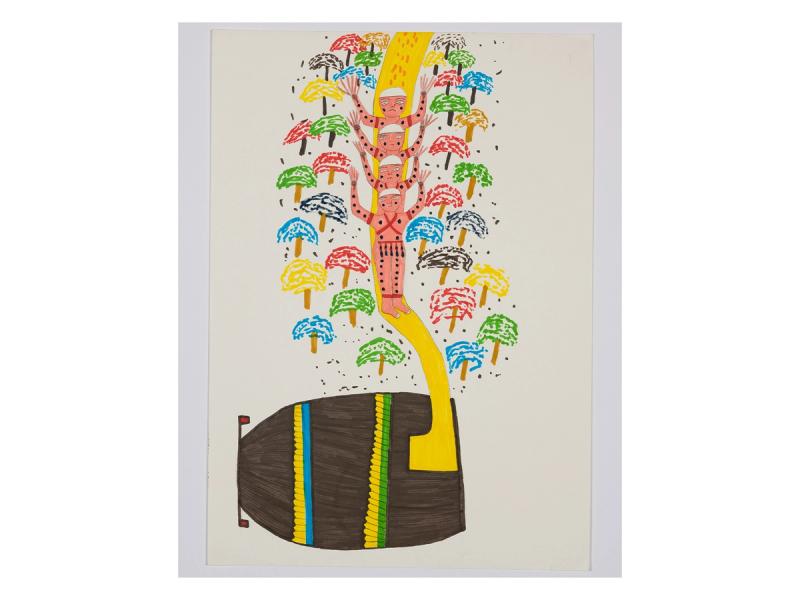

The deeply spiritual nature of the Yanomami is especially evident in the works by the Yanomami artists themselves. In one trio of felt pen drawings in particular, Yanomami artist Joseca Mokahesi vibrantly illustrates a hunter returning from the forest having been bit by the “tapir spirit”; a man dreaming that the Watupuri, the king vulture spirit, is eating both his image and body; and the dogs of the evil spirit Kamakari attacking a sickly woman. Toward the end of the exhibition, a work by the Yanomami video artist Morzaniel Ɨramari documents—in a relatively unedited, ethnographic format—a reahu funeral ceremony in which a group of Yanomami shamans collectively ingest the hallucinogenic snuff of the yãkoana hi trees. The mélange of authors, mediums, and approaches to the works in the exhibition communicates a strong sense of multiplicity, illuminating the diversity of perceptions and representations of Yanomami culture not only between insiders and outsiders, but within the Yanomami as well.

The second part of the exhibition chronicles in detail—and with the stated consent of the Yanomami—the trauma and violence experienced by the Indigenous people and their land since the 1970s, as well as the efforts taken by both the Yanomami and their supporters to quell and denounce this destruction. A timeline spanning one of the walls shows the mounting threats faced by the Yanomami since the 1900s as the Brazilian government and illegal gold miners have increasingly encroached on their territory, causing harm not only to their land but also to their health through the spread of infectious disease. One set of images shows the events leading up to and following the 1993 Haximu massacre, in which 16 Yanomami were killed by miners, four of whom were later convicted of genocide. The exhibition boldly pairs this anguish with action, discussing the concrete steps that have been taken to preserve and protect the Indigenous people, such as campaigns, protests, and health and educational programs organized by the CCPY.

Exiting the second segment of the exhibition and returning to the show’s entrance, I reencounter the photographs hanging throughout the “image forest,” and notice that the scenes that previously felt foreign now feel familiar to me, even intuitive. I realize that this is exactly what makes “The Yanomami Struggle” stand apart: You come away from it not just having seen the Yanomami’s faces, not just having learned their story, but feeling like you’ve sat with them in their yano, witnessed the presence of their xapiri, and learned the many ways in which they move through the world. As I near the entrance, I pass by a piece of wall text by Kopenawa—one that I first read upon entering—that encapsulates exactly this sentiment and its significance. “Those who do not know the Yanomami will know them through these images,” he says. “My people are in them. You have never visited them, but they are present here. It is important to me and to you, your sons and daughters, young adults, and children to learn to see and respect my Yanomami people of Brazil who have lived in this land for many years.”

![“Hii Hi frare frare” [Tree with yellow trunk] (2021) by Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe. (Courtesy the artist and Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/m8zvzebu/production/31dcaf4e00d170066644060fe1d2d42671c57204-1760x1320.jpg?w=800)