Nature’s Functional Forms, Billions of Years in the Making

Brooklin, Maine–based science writer and children’s book author Kimberly Ridley began her latest project by setting up a camping chair and a wobbly table in her backyard. Then she sat down, and waited. Observing her immediate surroundings, she began to notice a series of forms: A large, black-and-yellow orb-weaver spider spun a platter-sized web. Rotund toadstools and coral mushrooms with crownlike tops sprang up from the ground. A cup-shaped robin’s nest made of mud and grass balanced on a branch of a nearby tree. Ridley was enthralled with the formations she witnessed, and recognized that each phenomenon was a functional design billions of years in the making. She set out to learn about other extraordinary structures in the great outdoors, and chronicled her findings in her new book, Wild Design: Nature’s Architects (Princeton Architectural Press), out next week.

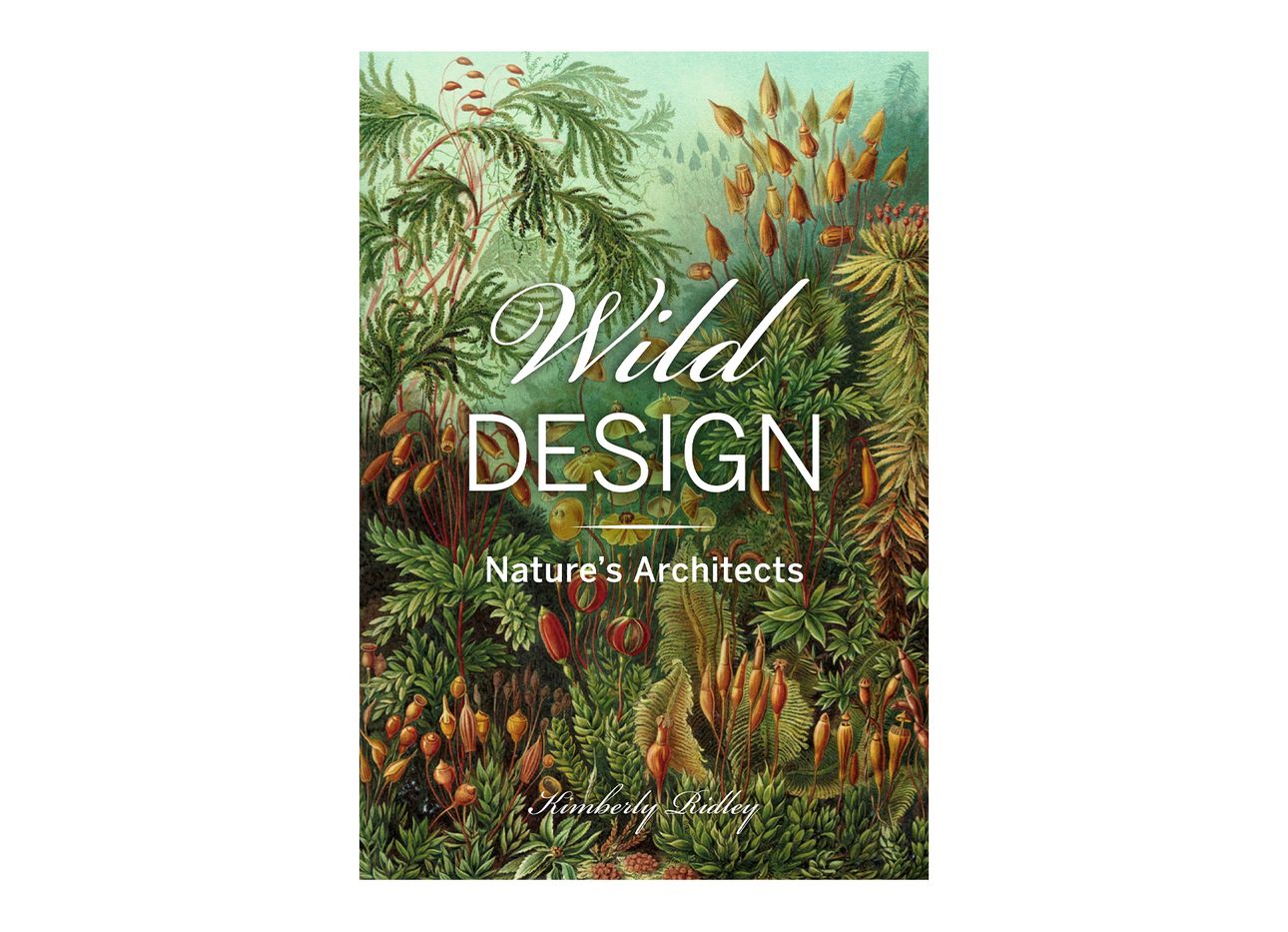

Through a mix of energetic essays and striking imagery, Ridley celebrates the shapes of protists, fungi, plants, animals, and other living things, whether via objects of their handiwork, or the bodies of the organisms themselves. She profiles a considered selection of nature’s alluring configurations, and intersperses her text with exquisite drawings created by natural-history illustrators from the mid-1700s to 1972, when the generalized study of flora and fauna began to more closely resemble modern science. The vibrant, highly detailed artworks suggest that their makers depicted their organic subjects with utter amazement—a sense that permeates the book’s eight chapters.

But the forms are practical, too. They’re created by, in Ridley’s words, certain plankton that serve as “nature’s tiniest architects” and fungi that act as “demolition crews and network builders,” as well as “arthropod engineers.” These shapes have even influenced the formations of human-made objects, from state-of-the-art technologies to the seemingly rudimentary items that we interact with on a daily basis. Ridley explains that the hexagonal structure created by bees, for example, has been pondered by the ancient Greeks and Romans and modern mathematicians alike, and has been found to be the most space-efficient shape. That characteristic has popularized the polygon’s use in a variety of designs, from the shape of nuts, bolts, and pencils to the mirror used in the new NASA-designed James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in December.

With each shape Ridley unpacks, readers will likely feel as if they’re viewing some of the most fascinating designs on earth. Although some can be seen only with a microscope, many can be observed by simply stepping outdoors, if we only take the time to stop and look.