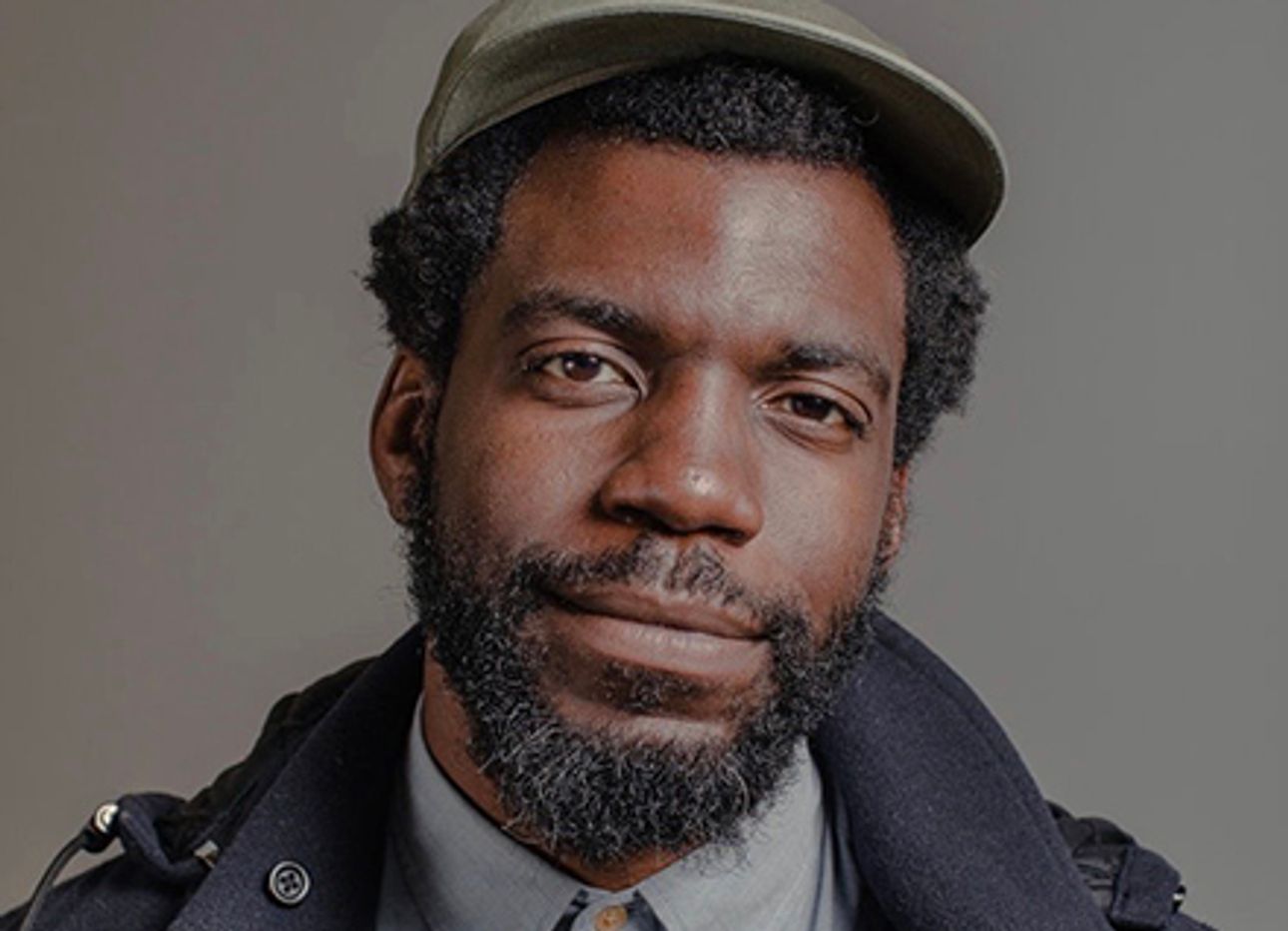

Whetstone Magazine Co-Founder and “Origin Forager” Stephen Satterfield on Food, Culture, and Identity

The co-founder of Whetstone magazine and host of the food anthropology podcast Point of Origin, food writer Stephen Satterfield spent more than a decade working as a sommelier before venturing into the world of media. A regular contributor to Esquire, Food & Wine, New York magazine, and other publications, Satterfield tells us about his role as a self-described “origin forager,” and why the world of food media is just starting to wake up.

After working in restaurants for several years, what inspired you to start Whetstone and move into the world of food media?

There are some overarching principles—ideologies, you could say—in assessing wine that I found to be transferable to other modes of thinking. More specifically, I’m talking about terroir, and analyzing wines through a prism of time and place, and environment and humanity, and kind of having that be the language.

While working at Nopa in San Francisco, in 2010, I began to befriend many of our purveyors at the restaurant, and through developing that community, became really inspired to chronicle their stories. That started off pretty modestly, as a Tumblr blog, but got progressively more ambitious, culminating in a brand with a voice and an identity that I decided to really pursue—but instead of through a hyper-local Northern California lens, a more global one. Whetstone is a food publication and media company that is dedicated to food culture through this specific framework of origins and anthropology. We don’t really say, explicitly, that our work is political—we believe it’s implied in the message—but how could it not be?

As a society, we’ve become so disconnected to nature and our food systems. How did we get here, and do you feel the ongoing pandemic will have a long-lasting effect on how we consume and rethink our food sources?

Our food system is owned and controlled by corporations, which really defined the entire twentieth-century history of industrialization in this country, and in many other countries. It’s the resulting impact of relinquishing more power to corporations to feed us, decade after decade, and moving further away from the agrarian tradition of the preceding centuries. Fast-forward to today, and you can now press a button on an iPhone to have food show up on your doorstep, which seems like a logical conclusion to all of that. The corporations really deliver on the original promise of the 1950s—with its microwaves, Easy-Bakes, and so forth, [up] through the modern grocery store—that you don’t have to be inconvenienced with canning or pickling things, or making soup stocks, that everything can be acquired, that it will afford you more time to spend with your family, to pursue this life of “American ideals,” whatever that may be.

At the onset of the pandemic, when the grocery stores were wiped clean, it was a frightening and really pivotal moment for a lot of people, and hopefully, a time to really start thinking more critically and asking: What and how do we actually feed ourselves, and where does our food come from? For us, it’s one of the essential questions.

As a co-founder of one the only black-owned food media companies in the country, what do you make of the current reckoning that’s happening in mainstream food media, at publications like Bon Appetit, and the difficult and painful conversations that are taking place?

Well, these aren’t difficult conversations for us because we have always been talking about this from the onset. And largely, the reason for our existence is the kind of racism that we experience—speaking of myself, personally—and basically felt uninspired by. We saw what was happening at these companies as antithetical to what we were trying to make, and in a sense, it gave us the guidance to understand what we didn’t want to do, in the way of appropriation, voice, and our editorial vision.

The reckoning is very necessary, and the erasure of other cultures—through appropriation, through excluding people of color from financial and professional opportunities—is in keeping with a centuries-long tradition of exploiting people of color, and specifically black people, for labor. This reckoning is largely about saying that the time’s up for that. We support it, and we think it’s only going to produce better products from the brands we love. I feel really sorry for the people who were harmed from all of the abuse that was happening within those organizations, but it does feel like there is a new enlightened moment. I’m not sure how long it will last, but it does unequivocally feel like a different moment—and that’s encouraging, to be in an unprecedented moment of racial justice.

One of the things we found particularly offensive is the working assumption, of the former editor [of Bon Appétit, Adam Rapoport], that the audience wasn’t sophisticated enough to absorb global or even diasporic cuisine. And in fact, the ultra-white filter applied to their stories actually wasn’t in keeping with broader food culture in the country, where people have been, in unprecedented ways, going to different kinds of restaurants and embracing all kinds of cuisines more than ever before. There was a real curiosity that they really could have led and brought their readers along upon, instead of undermining their intelligence by using this really, you know, milquetoast filter.

The power of this moment, and of your platform, is that people are hungry to learn more about food at a deeper level, and to recognize its cultural currency across so many spheres.

I’m always impressed with how sophisticated our readers are, and a lot of times they themselves will be independent scholars. I, myself, don’t have formal anthropology training, but I love reading about food origins, and there are so many others like me, who’ve used food as a pathway to deepening relationships to their own cultural, racial, ethnic, and religious identities.

Eating is something we all do and embody, in a way, which we can’t really say about anything else. We believe in the power of food as a way of radicalizing people, nourishing people, educating people, politicizing people—and we don’t really need to change our message to do that. We can tell really honest stories, whether about food culture in a contemporary context, or sometimes in a reported, anthropological story around indigeneity, that helps us understand how we got here. And I think a lot of that is a credit to the language, the vibe, and the products that we put out into the world, based around our working assumption about people’s comprehension, intelligence, and curiosity to keep up with what we’re talking about.