What the Sun’s Molten Surface Looks Like

After NASA’s Apollo 8 orbited the moon in 1968, its crew brought back with them the most stunning of photo souvenirs. “Earthrise,” taken by William Anders using 70mm color film, pictured our planet as a distant orb in the vastness of outer space—an image that would come to stand for humanity and, eventually, the environmental zeitgeist, popularized on the covers of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog and forever imprinted in the public mind. As Anders later said, “We set out to explore the moon and instead discovered the Earth.”

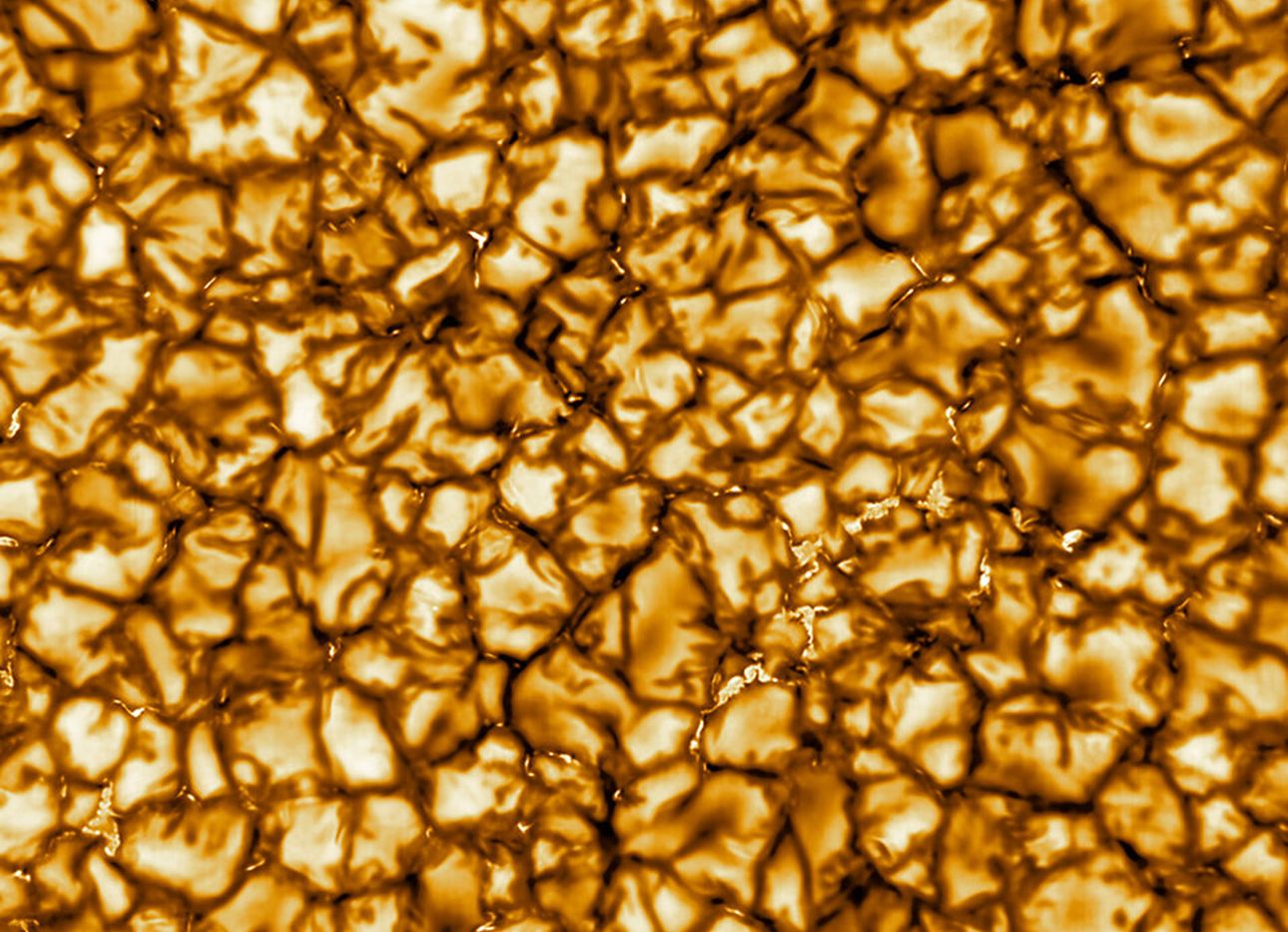

Half a century later, we’re now in awe of new video footage taken by the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, the world’s largest and most powerful of its kind, located atop the Haleakala volcano on Maui. The telescope’s recently captured imagery of the sun’s molten surface—the closest views yet afforded to human eyes—leave us both blown away by mankind’s widening gaze, and humbled by the expansive unknown. Some have likened its appearance to bubbling caramel popcorn, each kernel approximated to be the size of Texas. For those of us who remember watching Charles and Ray Eames’s Powers of Ten in science class, the pattern might also evoke the arrangement of cells of our own human skin, suggesting some eerie likeness and connection in the universe, across unfathomable time and scale.

In our current moment of uncertainty and existential threat amidst a global pandemic, compounded by the climate crisis, the images also serve as a sobering reminder of our place in the universe as tiny and insignificant, yet interrelated, specks of dust that dare to stare into the sun. As the Japanese government, referencing a Buddhist poem, recently noted on a box of donated medical supplies to China: “We have different mountains and rivers, but we share the same sun, moon, and sky.”