Elizabeth Alexander Explores the Grief, Gratitude, and Creativity of the “Trayvon Generation”

How do the generation of Black Americans who grew up in the past 25 years reckon with the tragedies that play out in their daily lives? And how do these forces shape them and their worldviews? In her new book, The Trayvon Generation (Grand Central Publishing), poet, educator, and scholar Elizabeth Alexander—who currently serves as the president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the largest humanities philanthropy in the United States (and who was the guest on Ep. 52 of our Time Sensitive podcast)—explores these questions, and others, by meditating on race, class, trauma, justice, and memory, and their influences on contemporary creativity. At this vital point in time and American culture, Alexander—a Black woman, mother, auntie, and lifelong teacher—positions art in her writing as a powerful means for understanding and self-expression, and for radically illuminating the country’s racism and racial violence.

Organized into three parts, with multiple essays in each, the book reveals how Alexander thinks about the contemporary lives of young Black Americans, and about the history of violence and grief knitted into the tapestry of the Black American experience. Interwoven with her writing are explications on pieces of music that speak to this cultural moment and act as protest songs—including Flying Lotus’s “Until the Quiet Comes” (2012) and “Never Catch Me” (2014), and Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” (2015)—as well as works from a range of artists, including Carrie Mae Weems, Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald, and Kara Walker. These images act as visual beacons to Alexander’s prose, not illustrating her words, but illuminating them. Part I, for example, begins with a detail of Lorna Simpson’s “Thin Bands” (2019), a desolate black-and-blue abstract screenprint whose tenor runs through the book’s assertive beginning.

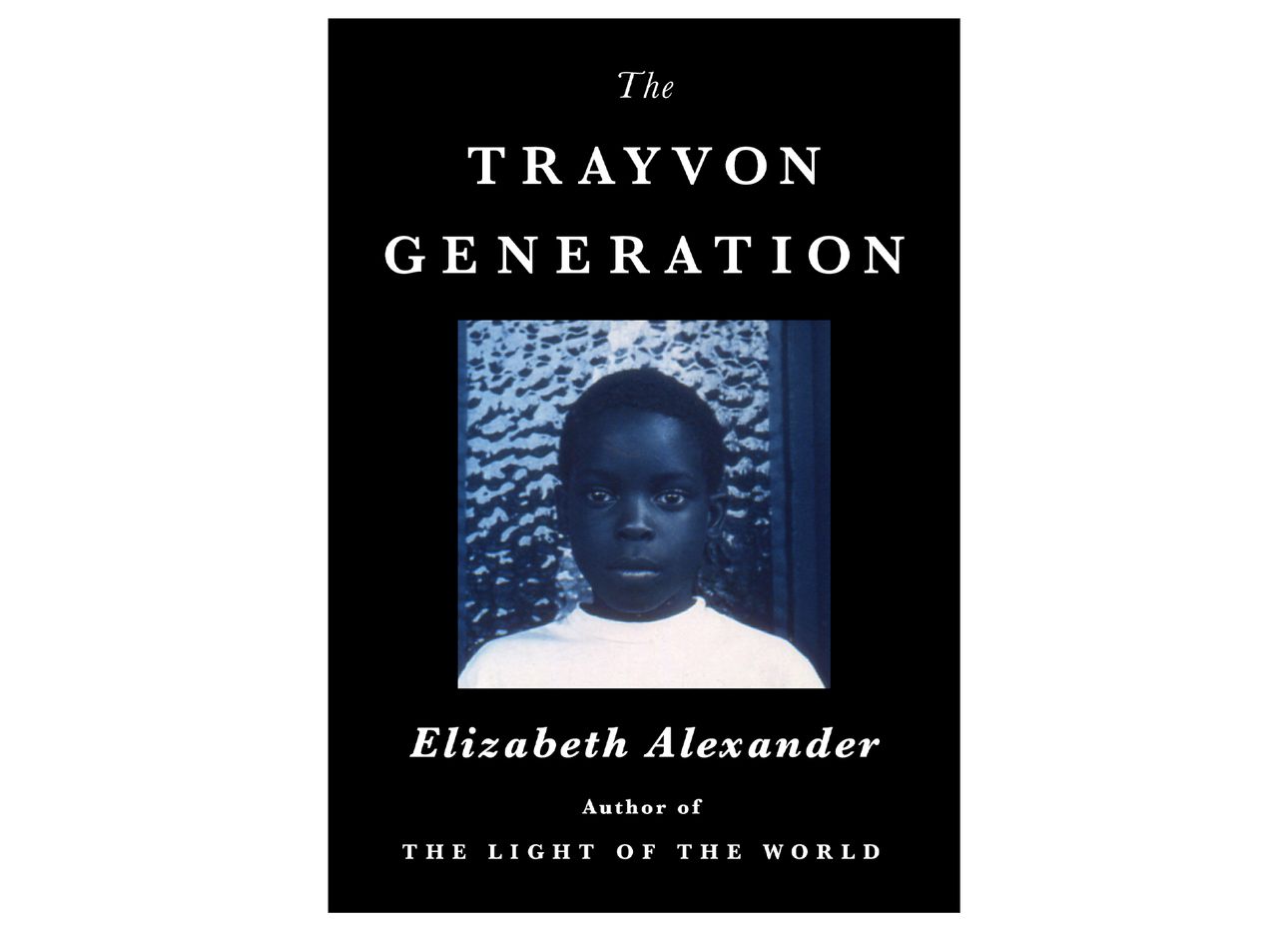

Part II, the book’s title chapter, originally appeared as an essay in The New Yorker in the midst of the civil unrest in June 2020 following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. (The piece later received a National Magazine Award.) In it, Alexander calls the young people who grew up in the past 25 years “the Trayvon Generation”—a reference to 17-year-old Trayvon Martin’s untimely death, in 2012, and the ensuing cultural moment that ignited a movement and ushered in a wave of activism against police brutality. It’s an age group, she writes, marked by the very public deaths of Black Americans, and also the weight of history that came before them. Alexander’s two teenage sons are part of this generation, and in this piece she writes to them, for them, and about them. Its opening paragraph—preceded by “Martina and Rhonda” (1993), a series of large-format Polaroids of two young Black women, taken by photographer Dawoud Bey, that nods toward the vulnerability of Black youth—offers a gut-wrenching review of those we have witnessed murdered: “This one was shot in his grandmother’s yard. This one was carrying a bag of Skittles. This one was playing with a toy gun in front of a gazebo. Black girl in bright bikini. Black boy holding cell phone. This one danced like a marionette as he was shot down in a Chicago intersection.”

Alexander describes the fear of keeping Black boys grounded and alive at a time when witnessing Black death is just a click away on our smartphones (and appears, over and over again, via videos that are often seen out of context), and when Black life is constantly threatened by forces outside of her control—in one incident she describes, her community’s block watch in New Haven, Connecticut, praised neighbors for calling the police on two Black kids riding bicycles. Throughout, Alexander considers how Black youth are finding resilience and strength in a moment when they are constantly faced with traumatizing displays of the fragility of Black life, and how Black Americans move not to forget, but to remember, and move to keep living.

Elsewhere, Alexander provides lyrical contemplations on subjects both broad and specific, including dance, poetry, Confederate monuments, and coming face to face with racist imagery on the campus of Yale University, where she was a professor and department chair for 15 years, until 2016. Taken together, the essays that shape The Trayvon Generation provide a space for Alexander to begin a dialogue that artfully steps backward and forward through time, reflecting on how society has changed, and the spaces where growth is still urgently needed.