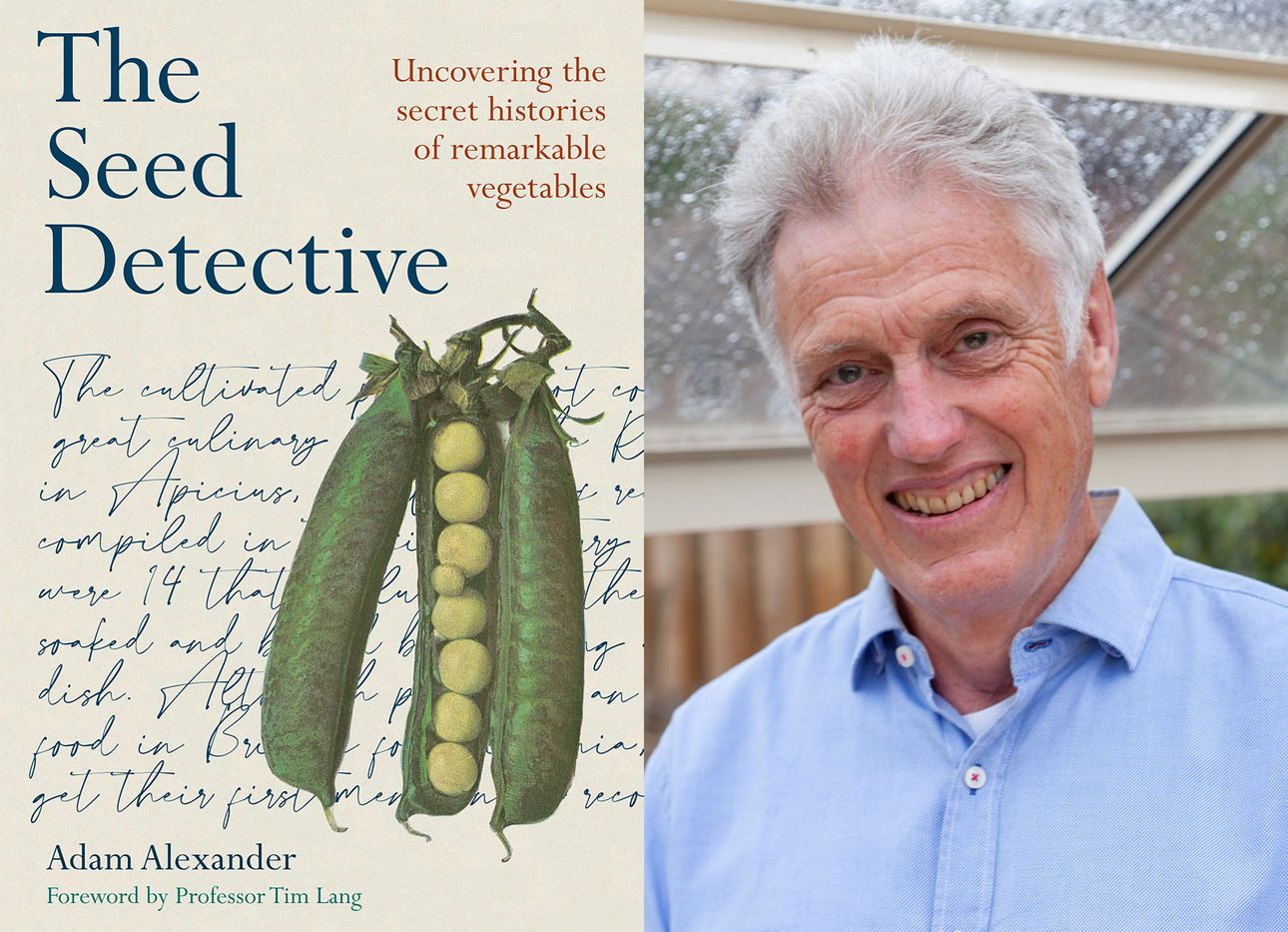

“Seed Detective” Adam Alexander Imagines a Better World—Through Rare, Endangered, and Unusual Vegetable Varieties

For British author, TV gardening producer, and “seed detective” Adam Alexander, the supermarket serves as perhaps the finest symbol of our modern food systems and their discontents. Of course, there’s undeniable quantitative material abundance, with aisles upon aisles of vegetable varieties—chopped, pickled, canned, and fresh—all that one could imagine within the confines of some idea of a generic palette. But it arrives at a qualitative price, and not just in terms of flavor, but also in context, in our ability to see this food as a part of our own story—as a connection to the land we live on or a cornerstone of the traditions we uphold. Vegetables are more than just so many anonymous pounds on a scale. “This strong connection with the land and what we grow and what we put in our own mouths has been lost, especially in the U.K.,” Alexander says. “To me, it’s really important that we try to reconnect and recognize that these vegetables are part of our human story and, in that way, we can do a lot to serve rare and endangered varieties.”

For the past 30 years, Alexander has explored the world, preserving, growing, and distributing local varieties from around the globe, ranging from Burmese Sour tomatoes to the french bean varieties of his native Wales, where he resides and tends to his impressive garden. He has now collected his deep knowledge—and these bold adventures—into a taxonomy of sorts with The Seed Detective, a book that’s divided into 14 sections and organized around 14 different types of vegetables, starting with those native to the eastern hemisphere before traveling west for the last six chapters..

His treatment of these veggies is impressive, both for its exhaustive breadth and charming color. Alexander winds through the historical roots of one notable variety or other and connects it to his present-day encounters.The latter aspect of these stories includes excursions to everywhere from Damascus to the deserts of Rajasthan, from Myanmar to the American Southwest. The chapters do an impressive, albeit sometimes overwhelming, job at showing the evolution of different crops into what we know today, tracing their routes (and roots) around the globe and analyzing what’s been gained and lost along the journey. The book also finds room for a number of colorful anecdotes that serve as off-brand history lessons, be it Henry IV of France inadvertently popularizing garlic by adding it to holy water for protection from evil spirits or philosopher mathematician Pythagoras’s anti-bean philosophy, which allegedly led him to accept death at the hands of assassins rather than flee into a field of favas.

Above the sheer entertainment factor, though, there is a more serious goal Alexander has in mind. He elevates growing and preserving varieties to a metaphysical context, an act of commune linking one’s life to a human story that spans centuries into the past and, hopefully, centuries into the future. “I hope, in the book, by bringing these vegetables to life, and by sharing the extraordinary relationships that we’ve had with them for thousands of years, it’ll at least inspire people to feel more engaged with them,” Alexander says. “And if they don’t grow [these vegetables] themselves, to go seek them out and be part of the kind of future that needs us to have greater diversity of crops, that needs us to feel much more closely related and involved in them.”

The practical import that goes along with all this is that, as the climate crisis disrupts agricultural supply chains, the genetic diversity of crops reemerges as an asset in stabilizing food production. As Alexander acknowledges near the end of the book, recentering food consumption around sustainable, local agriculture is an incredibly fraught issue, one facing obstacles ranging from financial barriers to access to the exploitative precedent behind the treatment of local growers to the grip of capitalistic supermarket culture on the collective imagination. But within a century that saw the extinction of some 90 percent of all varieties of fruits and vegetables, the very existence of this new conversation around changing the paradigm of mass-produced monoculture may be the first step toward accepting that reconnecting with the food we eat is both a possibility and, perhaps, a necessity.