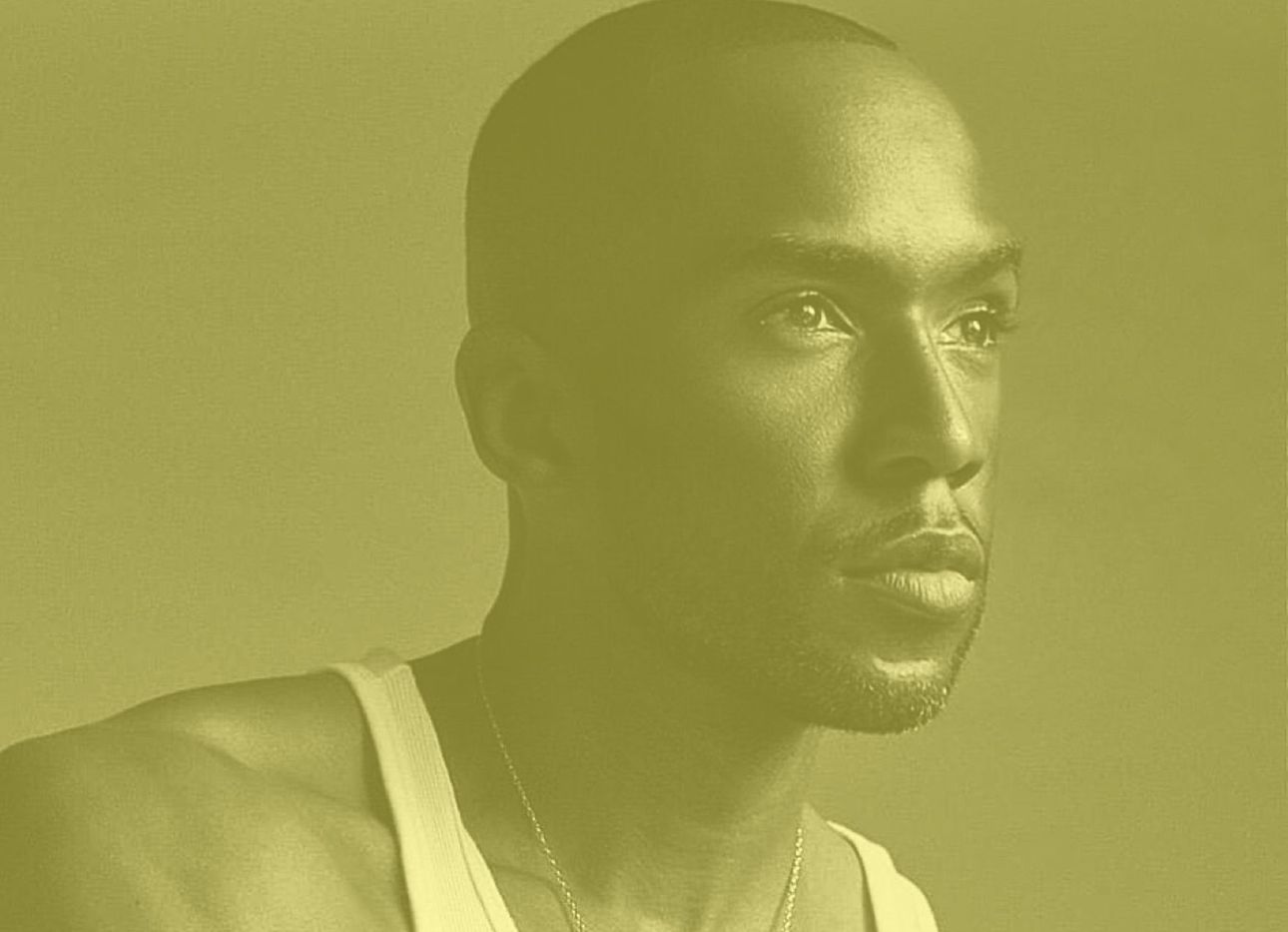

Jaé Joseph on Broadening Notions of Luxury and Well-Being

As the founder of BAO (Black Apothecary Office), Jaé Joseph aims to create more than just another skin care company with yet more hydrating and exfoliating cleansers, toners, lotions, and creams. (BAO does produce a line with all that, too: a range of papaya “essentials” that pull from Joseph’s Caribbean roots and embody a sensibility he describes as “bodega beauty.”) Joseph—who, in addition to running BAO, is also a cultural producer working in the worlds of art and fashion—is especially focused on transforming the way people interact with Black- and Latinx-owned beauty and wellness brands. “‘Black-owned’ does not mean only Black-consumed,” he says. “Forty to forty-two percent of the client base for my product line are not people of color.”

Here, Joseph talks with us about his family as his superpower, why awareness equals well-being, and how the practice of journaling has completely changed his life.

Jaé, you founded and launched BAO in 2020. What was your impetus for creating it?

Six months prior to the pandemic, my father passed away. I was also coming out of a long-term relationship. So mental health and wellness were at the core of my trajectory. That’s what I had seen for myself: “This is the next phase of my life. This is where I want to go.” I asked myself, “What can I contribute to the world that is not too far off from who I already am and some of the rituals and practices I already have in my life?” It was to create a wellness platform for people of color, as well as for people who identify with the LGBTQI+ community.

It’s been two years of building, and today, it’s been a year of us developing our own product line, which is based on my Caribbean heritage. All of the products are infused with papaya enzymes, and this is great for rehydration. It’s great for inflammation. It’s also great for scarring. It [also] helps people of color with eczema.

Melanated people deal with all of these things—dehydration and eczema. I grew up with eczema as a child. I had it on the front of my legs, the back of my knees, and sometimes my hands. A lot of other children grew up with it or they’re born out of the womb with it, and they deal with it for the rest of their lives. So, I wanted to include an ingredient in this product line that was a healing agent and also reminiscent of my Caribbean culture.

You’ve previously talked about wanting to bring cultural integrity to beauty investing. I’m wondering what this actually looks like. What’s your vision for BAO? How do you describe what you do?

For me, cultural integrity in the line of work that I’m currently in—the space of beauty and wellness—is about staying true to my heritage as well as my own daily practices and rituals, and not watering them down. I think that a lot of times, these larger companies go in and buy these brands [owned by people] of color, and then you no longer see the creators as a part of the team or the decisions being made at the top.

For me, it was important that I created something that was reminiscent of my own artistic practice—because I do consider it an art form—and didn’t cut corners. I wanted a luxury brand. I spoke to Allure magazine around a year ago about how Black-owned does not mean only Black-consumed. Forty to forty-two percent of the client base for my product line are not people of color.

I wanted to set the bar even in my marketing and packaging, which has all been very grassroots. There really hasn’t been a budget for marketing, because I wanted to be conscious and build a sustainable brand from the inside out. When you’re an entrepreneur, you’re bootstrapping. I think that makes a brand even more conscious of setting boundaries around how much money you’re going to spend on marketing, who you’re marketing to, and what the messaging is. We’re not a celebrity brand. Our core audience is either people who want to know more about the ingredients—how they can be healing agents or how they can include them in their own daily practices with the products they already have—or people who have felt like they haven’t been seen. Now they see a product that is reminiscent of their background, their heritage, or some sort of health or skin issue that they’ve had in the past.

You mentioned rituals. You were raised in a Caribbean-American family in the Midwest, surrounded by these strong Black women—mothers, sisters, cousins—who all had their own regimens. I was wondering what you learned from them. Also, could you share some of your own daily practices? What are some of the things you frequently recommend to others or that you do yourself?

I always say that family is my superpower. They are at the core of everything I do, every decision I make, and every fond memory I have. Family is my actual superpower. I try to instill that into my younger nieces and nephews and let them know that if they ever need support or feel empty, family is their cup. Like, your cup is here, come and be filled.

Growing up in a religious Caribbean household, there were always these moments. You know, my grandfather, he would get up in the morning, and the first thing he would do is make a cup of loose-leaf tea. My grandmother would then go in, and she would fry plantains for him and make fish and rice that would sit on the stove for the entire day. There was always fish and rice and plantains on the stove. That was their form of wellness. It was almost like a practice for themselves and for their ancestors. This abundance practice meant there was always food and fruit on the table for anyone that came over.

On the flip side, there were always these lavish dinner parties at our house. Always. I say that because I think I saw the practices of my grandmother, how she would get up and get dressed every day and be so feminine and beautiful. My grandfather would do the same thing—everything would be so tailored, and he would have on the best cologne and fragrances. There’s a certain fragrance from the Caribbean that he would always put on. He would have that on under his main fragrance, whatever that was. Normally it was an Hermès cologne or something like that. That was a form of wellness and a form of protection for him. It cleared his mind and energy.

Prayer was also a daily practice, obviously. Which leads me to talk about how journaling has saved my life in the last two years. The practice of journaling has one thousand percent changed my temperament, my consciousness, and even made me realize that I’ve had an unawareness of myself before. So that’s something that I often go to when people ask me, like, “What are your wellness practices?” Or “How do you cope with mental health?” Or “How did you deal with the pandemic?” My practice is journaling. Every morning, when I get up, my intent is to journal so that I can script out my day. My intention is to journal so that I can fuel divine health, divine wealth, divine peace, and divine consciousness. This has changed the trajectory of where I could have seen myself, say, two or three years ago. It has been the best thing for me.

Let’s get into how you think about the words “well-being” and “wellness.” How do you define them?

When I think about well-being or wellness, I think about awareness: being aware of your body; being aware of your mind; being aware of how your body moves, what your body needs, and when you need to be still. I think it’s quite mesmerizing how we can spend hundreds and thousands of dollars on counseling treatments and all these things for the mind when we can actually heal all of these things right at home. We’ve been conditioned to think that because we don’t have access, we can’t be well or we can’t be at our best in terms of fitness or mental wellness, which is false.

“Luxury” is another one of these terms that gets thrown around a lot.

Absolutely.

I was wondering what it means to you, particularly in the context of well-being? And, if we’re talking about luxury and Black Americans, there are also people like Dapper Dan and the late Virgil Abloh, who have been leading figures in redefining and re-categorizing what we might call “luxury.”

Yes. Dapper Dan. Love him, love what he’s done. He’s created a lane that no one else can ever touch. And he’s influenced so many people right there in his own community. He’s done more for his community, for the people of Harlem, for Black people, and for Black people in fashion. He’s opened up the doors for people like Virgil. He’s set the template, and he’s been the uniform for it.

Then, of course, Virgil. When it came to luxury, I think Virgil just wasn’t about name brands. I think that a lot of people think that as well. He was more about aesthetic and design and feel. I think that when you listen to hip-hop culture or rap music, it’s not always just about the name brand, but about how you’re feeling. And, for me—while I’m speaking about feeling—luxury is a feeling. That’s it. It’s not a price tag. It’s not a name brand. It’s a feeling. That’s why I created BAO Essentials, which is my product line. I consider my brand a luxury brand, but it’s one thousand percent accessible luxury. It’s a luxury that’s going to make you feel good from the inside out.

To finish, what to you, Jaé, is the good life?

For me, the good life is actually what I’m currently living now: being present, being aware of my body, being aware of my surroundings, listening to my body, setting boundaries for myself, setting boundaries for others around me, and staying disciplined in that practice.

This interview was recorded on September 6, 2022. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity.