vanessa german on Art as a Way of Life and Love as a “Human Technology”

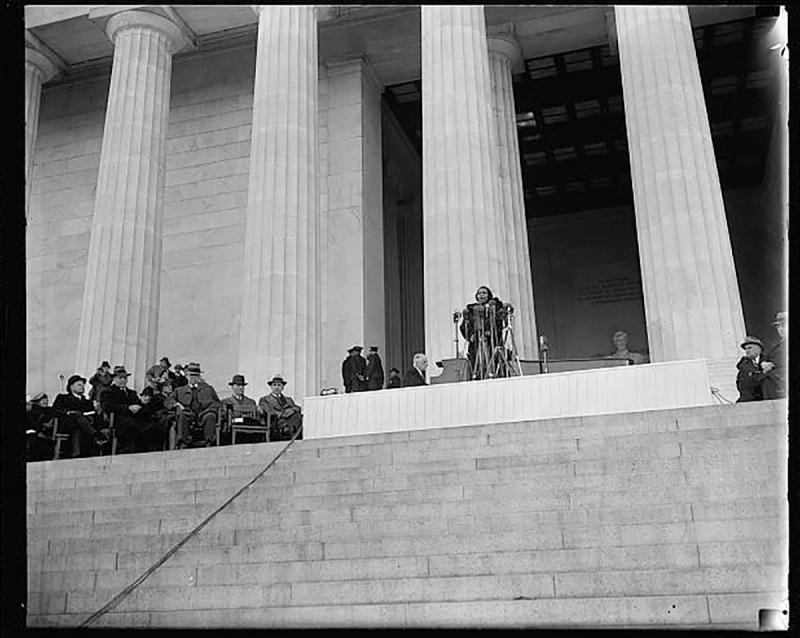

When the artist, performer, and poet vanessa german was selected to design a temporary memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., as part of the “Beyond Granite: Pulling Together” exhibition (on view from Aug. 18 through Sept. 18), she quickly found herself turning to a catalytic moment in American culture: the contralto opera singer Marian Anderson’s 1939 Easter Sunday concert at the Lincoln Memorial. Attended by 75,000 people in the then segregated U.S. capitol, with millions more listening on the radio, the event put Anderson—who was Black and had been refused an indoor concert by white organizers—in the nation’s spotlight. It was, and remains, a beacon moment in U.S. civil rights history.

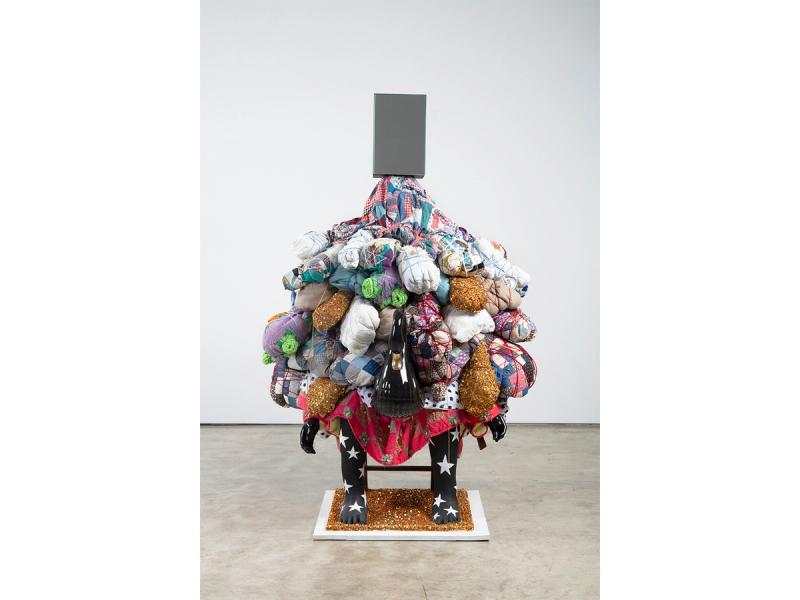

german’s statue, titled “Of Thee We Sing” and presented at Lincoln Memorial Plaza, is an abstract figurative form depicting Anderson held up by the hands of the 1939 event’s attendees (collected by german from historical images). On August 19, german will also present “The Blue Walk,” a live performance involving song and movement, with german walking along the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool in a custom gown. As with much of her work, “Of Thee We Sing” functions as both a memorial and an altar. “I wanted to make a monument to the human heart,” she says. The artwork is also an unabashed tribute to love: “I’m really always thinking about love as a human technology.”

I recently spoke with german, via Zoom from her home in Asheville, North Carolina, in a conversation during which she shared how she’s been thinking about memorialization practically her entire life (she grew up in Los Angeles within the dual contexts of gang violence and the 1980s HIV/AIDS epidemic); why she recently relocated from Pittsburgh, her longtime home and base, to Asheville; and some of the enduring lessons her mother taught her about art and creativity. It is, without question, among the most kaleidoscopic, heart-filled interviews I’ve ever had. Here, a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

What is a memorial to you? Let’s start there.

Just even hearing the word memorial makes me think about the living in reflection of the dead. It’s a way for the living to hold space in many different shapes for the dead.

With that definition in mind, what was your approach to conceiving and creating “Of Thee We Sing?”

I was given the prompt “What’s missing?” What’s missing from the National Mall? What stories, what people, what representation is missing?

For me, the Mall is not always a place I’ve felt welcome. There are ways that the Mall feels really cold. The memorials for wars…. There’s such a contrast for me between recognizing and having these exquisitely sculpted monumental structures to the accumulation of death. I’m always wondering, how do you honor people? What’s the opposite of a war memorial? How do we make space for peace? How are we cultivating a way to be able to be in community with each other and through conflict that is not accumulating death?

The idea that humans can go through conflict and not accumulate death is not new. But where is that in relation to monumental structures, to what they call “the sacrifice” of these, a lot of times, young male humans? I always think the best way to honor is to not put them in that situation again. Where is the effort? Where is the energy? Where is the monumental momentum toward not putting large populations of young humans in positions to be murdered or to become murderers? That’s something about the National Mall that makes me feel very sad.

Every place I go, one of the weights I have is just the constant PTSD of being a Black person in America. When I’m in D.C., I’m like, “What did Black people build that we did not get credit for, that we built under duress and under the threat of brutality to our bodies?” I want to go and honor that, because there’s no plaque that says enslaved people built half of the Washington Monument and the White House and that little cabin that’s on that corner. There’s nothing that says you’re looking up to something that was built by human beings who did not have liberty, which is the soul’s right to breathe.

The National Mall for me is very complicated and heavy. [With “Of Thee We Sing,”] I was not thinking about making a memorial. I was thinking about what’s missing and why it’s missing. That prompt came alive for me given that there was also the resource of Marian Anderson’s 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial.

Yes, “Of Thee We Sing” pays tribute to Marian Anderson. I was fascinated to learn that your mother grew up listening to Black opera, so this was a subject that—

Yeah! I was aware [of Black opera] as a little girl. I knew who Leontyne Price was. I knew who Jessye Norman was. I knew who Marian Anderson was. I was not shocked that there were Black opera singers. I knew that they were extremely special. My mom was a fan. My mom would cry at opera, and I didn’t understand why. I didn’t understand crying-because-art-moved-you when I was 6. It would embarrass me. It would scare me that she would be so moved by somebody’s voice.

Were you seeking to capture some operatic sense of that in this work?

I had done some research about the 1939 concert—which wasn’t the focus of the Marian Anderson I knew. Marian Anderson was already an older woman when I was a child. I was interested in entering into that “What’s missing?” prompt by something that had been so present at the Mall. Seventy-five thousand people looking at one Black female body, looking at one hundred twenty-five pounds of woman. Seventy-five thousand people just focusing on one Black woman in 1939, when it still wasn’t a crime to rape a Black woman. No white man went to jail for raping a Black woman until the late sixties. This was somebody whose body could be brutalized and no justice done. This is a woman with an incredible voice whose body was turned away from Constitution Hall—three thousand people can fit in there, maybe.

What really stood out to me was that, at the National Mall, there are no monuments to love. A memorial for dead soldiers is not actually a monument to love. For me, I’m really always thinking about love as a human technology. One of the reasons why the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is so difficult for my father, who was a vet, to be around is only because he loved the soldiers that he was with. He was so young. My dad was 19, and had already lost so many of these guys they knew. They clung together so tight. What makes it so alive for him is that he loved them. I wanted to make a monument to the human heart.

I saw this one picture of the Easter Sunday crowd [at Anderson’s 1939 concert]. It was an old white man who looked like he was from the “American Gothic” painting. He looked like a farmer from a dusty place in Idaho. And his body is crammed next to this little Black boy with a flat cap on in his Easter Sunday best. And he’s crammed next to this Black woman. It’s very tight. I was like, “Y’all don’t seem to care as long as you can hear the Black woman sing.” I imagine that’s the vision that King had when he said he saw the “beloved community.” This is the beloved community.

In 1939, even with segregation, they just wanted to be there. That told me a story about the human heart, about all this bullshit that falls away when you’re standing before something miraculous, or you’re in a place of wonder and your singular focus is to bear witness. I was like, “I don’t have to construct some highly fabricated monument to the human heart that’s conceptual. It’s enough for us to be confronted with the images of the crowd of the Easter Sunday concert.” Because there was a whole bunch of stuff that was not important to that crowd, and one thing that was very important. The things that fell away were the chaff. It was not important that you’re next to a little Black boy. It was not important that all these white women are next to the Sunday grandma, Black Baptist church women. It didn’t matter.

For me, especially at a time when…. I have never felt threatened in America because I’m a Black person or because I’m a queer person—until last year. I’ve had issues with the police, treating me certain ways, doing shit to me. But just white men at the grocery store—I had never felt like a target until last year. So 1939 to 2022, to be an artist—as Marian Anderson is an artist—in a Black body…. There’s a wound. There’s this national wound that you think it has closed up, but it’s so infected under the surface that, as soon as something nicks it, the toxic sickness of the infection comes out.

It’s 2023, but I can look at this image of the chaff having fallen away from the eyes and the hearts of people in the crowd of this concert. So that became my monument to the human heart, just the vision of the crowd. But also, it’s an abstract figuration of her, the body of a Black woman, in Washington, D.C., where so many presidents of the United States either suckled from a Black woman’s breast—they were wet-nursed by a Black woman; they were nannied by a Black woman—or they raped Black women, as T.J. did. Black women were some of the real foundations to the people we call the “founding fathers.”

I wanted to physically represent that Black woman who was the sole focus of seventy-five thousand people. And it’s not lost on me that the white women, who said her operatic voice with the Black body could not perform at Constitution Hall, that they ended up being there in that group of seventy-five thousand people, watching her sing. That, to me, is its own story about what fell away from their eyes.

I don’t know if you’d be open to speaking about this, but why did things change for you last year?

I’m not working in Pittsburgh anymore. I’m now working in North Carolina. I needed to find a place where I could work again. I had been stalked. My address in Pittsburgh is so public—people would be outside of my house. I felt so unsafe that it was actually paralyzing.

I think the only way I can survive in my life is to make art, and I don’t want that to sound corny or romantic, because I always get this sort of reflection from “professional” adults when I say that if I didn’t make art, I couldn’t live—that that’s somehow a flimsiness or a weakness of my character. But it is actually a real, fine-tuned understanding that I have about why I’m alive as a human being. This reflection is connected to the way that white supremacy separated people from their humanity, separated your humanity from your purposeful contribution to community and turned it into a form of labor. We live in a country that actively knows minimum wage is not living wage. What does that mean when your country, “liberty and justice for all,” knows you can’t make it with what forty-five percent of these companies are paying service workers? We are not our labor. My existence is about creativity. It is about transformation. So I do not want to diminish that.

But I was not able to work there. So I came to North Carolina, to Asheville, where I knew it was a community that voted to give their Black and Indigenous citizens reparations. I knew it was a really gay place. Even though I lived in the hood in Pittsburgh, the amount of homophobia I experienced from Black people, it was so stupefying and so stupid at the same time. The older Black people who’d be like, “Bulldagger!” “She’s a carpet muncher!” I would be like, “Is it 1929? Where did you learn homophobia from? Nobody uses the word bulldagger. Only you know what that means, because you were born in 1929, and you need to stop.” So I also moved to not experience homophobia, just to have some softness.

But it’s still North Carolina. So the real estate agent, when I was looking at places, she said, “Could you drive past this property during daylight and let me know just how you feel?” I was like, “That’s weird. Why are you saying that?” There was a guy named Madison Cawthorn, a rep from North Carolina. He was really, really extreme [against gay rights]. She goes, “I don’t feel safe over there as a white queer woman. Before we go into the house, just drive through the community.” I was like, “If you don’t feel safe, I’m not even going to do that.”

What happened was, I’m a Black body, and I’ve been threatened by white men here. The white men with pickup trucks and the American flags off the back. I could pull up text messages that I got from the carpenter who worked on something for my kitchen, who sent me a text message to tell me why Black people should be thankful to white people for slavery and why Black people owe white people reparations. I was like, “I’m not going to deal with this. I don’t want to work with you anymore.” Then he started to send me threatening messages.

I bought three and a half acres of land five miles outside of Asheville, but it’s the place where the North Carolina K.K.K. people had that rally. One person was like, “Yo, be careful. That’s the K.K.K. place.” I didn’t think anything of it. I was like, “I’m done being afraid of white people. I’m done being afraid of white men”—I don’t want to do that anymore. Until the people who live across the road barbed-wired this section of my property off so that I could not cross over. This section is the size of a sidewalk—four feet—and they barbed-wired it to prevent me from crossing over to the road. That was such an aggressive act. But they’re QAnon people. They’re January 6 people.

I’ve had five different experiences with white men here that I’m like, “Oh, it’s different [in North Carolina].” I left Pittsburgh to have an experience of safety, but I still have to be vigilant. It’s just sad. I worry when I go to the grocery store that that carpenter will be there. These angry white men, they’re angry at the government, and they have this version of me in their imaginations.

And then also being gay.... I’ve never had a problem being a lesbian until this year—people just saying things that are so ignorant and so hateful and so violent. I can’t even. They’re full-grown adults. I do not engage my energy in educating them. I just have to be like, Wow, this is so strange that you were fine with me in my art the last fifteen years, but now, all of a sudden.... I can say something about loving women, and I’ll get messages about how I’m forcing people to accept my sexuality and that I keep putting it in their faces. This is so weird. But that started to happen this year.

Honestly, I’m hoping that the Marian Anderson figure is safe in D.C. because I saw what happened to Tschabalala Self’s work overseas, how they painted that Black figure white with spray paint. I’m just holding the space for the fact that it’s the National Mall. Nobody’s watching that sculpture at night. I just hope that it’s okay. I hope people respect it.

I appreciate you answering my question in that way. You just listed multiple harrowing, heartbreaking instances in which it’s been so incredibly hard for you to be a queer Black woman in America. Do you think, in some ways, your art-making is your savior from all of that?

Well, I remember coming across the Toni Morrison quote where she said to Black artists, “Be wary of spending your creative energy in your life trying to tackle racism and white supremacy.” She said “It’s a very violent distraction. Do not allow yourself to be distracted." So when I heard that, and I thought about how consuming things were in my mind, I was like, “She’s right. I’m not doing this.” People are always like, “Oh, vanessa german, she’s an artist and an activist.” I was like, “Yo, white mainstream politics is going to see anything that a Black person does to take up space as an act of ‘activism.’”

Yeah, that’s so true.

Then they’re going to say that you’re “brave.” You only experience that because you hold a space of limitation. The white imagination has so much limitation around Black life and Black bodies and Black creativity and Black joy. People find out that I have artwork in museums, and they go, “Wow!” I’m like, “That’s you. That’s your imagination of who I am, and what the possibilities are and how expansive my life may or not be. That should not blow your mind. It should also not blow your mind that I own property, that I have land and a house.” But you know what also blows people’s mind about me? That I do not have children. It’s just unfathomable that I’m a Black woman with breasts and I’ve never breastfed another human being.

The reality of “what is the savior of my life?” is that I found out why I am alive. It took me almost dying to find out why I instinctively move the way that I move. I can chase back to my youth the things that fascinated me, that kept me up at night, and they are absolutely critical engines to my practice to this day. I’m like, Oh, I get it. I have always been this person. I have always been an artist. And that’s where I came to the understanding that being an artist is a complete human identity. It is not merely a vocation. It actually isn’t even a practice. It is a way of being alive as a human being. So yes, my survival is here, my existence is here, but also my insistence is here. My resistance is here. My medicine is here. That is a wholeness.

When I was preparing for this interview, I was thinking about how the first work I ever saw of yours in person was “Reckoning: Grief and Light” at the Frick in Pittsburgh, a piece that acts at once as a memorial, an altarpiece, and an elegy to all this police violence—George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain. Other works of yours come to mind here, too: “sometimes.we.cannot.be.with.our.bodies,” from 2017, and “A Love Poem to Nia Wilson,” from 2018. You’ve been thinking about memorialization for some time.

Well, it’s been a part of my whole life. I grew up in the eighties in Los Angeles when this unknown illness became HIV/AIDS. I watched my neighbors disappear. AIDS was such an enormous part of my childhood because people were disappearing and we were not discussing their deaths. People wouldn’t say that a person died of AIDS; they would say they died from “The Big C.” It didn’t sit right with me as a child that I was not experiencing, in my world, a reckoning with these deaths. They were public deaths, and there was no place or time to honor some of our neighbors. So, when I was a kid, I started doing my own memorials for people who died.

Wow.

There were these two girls whose mom had sent them—in L.A., liquor stores are a big thing. You call them “liquor stores.” They have alcohol, but they also have Now and Later candy and so on. So she sent her daughters to the liquor store to get milk. I’ll never forget it. They got killed in a drive-by shooting. Two little girls, two small bodies, laying in front of the liquor store, and the milk running with the blood. As a kid, it scared me so much that they didn’t know they were going to die. I couldn’t process the complete sudden coldness of death as a kid. So I started doing these little rituals.

I made sure that I listened to the news and that I knew their names. Then I found the article in the Los Angeles Times the next day, and I took the article, and I cut it out and I folded it up in an old tin can. I dug a hole in the backyard. I don’t know where I came up with this. I took a piece of my little-kid jewelry, and I put it in there. I had to have a way to honor their life.

I did the same thing for Ryan White, a kid who had hemophilia, who died of AIDS. As a kid, I understood that it was very special to be alive. I understood as a kid how momentous it was to have all this energy in human form. I also had this big feeling that I would honor my own life by honoring the deaths of people in my community. I started having secret memorials.

Death, you see it in my work. That Nia Wilson piece, what’s a trip about that is I was in California when she got killed, a horrific public death on the [Bay Area Rapid Transit] train. But she was with her sister. There was a newsreel I was watching hours after she got killed, and it was still an active crime scene. In the newsreel, you can hear, over the sound of the reporter, her sister screaming, and all she keeps screaming is: “My sister! My sister! My sister!” The reporter is distracted by the sound of this girl’s grief. It just slammed into me, the devastation of the sudden horror and the violence of the death of this person.

One of the things I recognize is we only grieve because we have loved, but we are not honoring the technology of our love in ways that are commensurate with how we will grieve. I want to bring those things closer together. You saw the “Reckoning” piece. “Grief and Light” is part of the title, which is why there’s a bench. You can sit down in that installation and you hear the opera—it’s called “Requiem for Rice.” And do you know the story about rice in America, in the South?

Mm-hmm. Actually, I spoke about this very subject recently with the culinary historian Jessica B. Harris on our Time Sensitive podcast.

My friend Dr. Edda Fields-Black has written books about rice culture and how you could keep enslaved people alive longer if you fed them the same food.

You also hear, over the whole soundtrack—I don’t know if you remember this—the sound of me counting one second at a time: ten minutes and thirty-six seconds. That’s the amount of time that that police officer kneeled on George Floyd’s neck. To sit there and to take it in and out of your body with breath—there are only so many ways that things come into your body. You inhale it, and then you’re letting it process and then come back out.

Thinking further about your childhood and your upbringing, I wanted to touch on the fact that your mom was a fiber artist and quilter and costume maker. You and your siblings grew up making your own clothes and books and toys. Can you reflect on how you view the creative atmosphere you grew up in the context of your work today?

My mom was a technical genius. She had a really, really high I.Q. She went to college when she was 16 years old, but she also was a light-skinned Black woman who grew up in Jim Crow. She could have passed, but chose not to pass and was an activist. What’s interesting to me about the way we grew up is that I could have had one of those Black mothers who was like, “You will go to college. You will get a master’s degree or a Ph.D. Education is the way. You have to get good grades. I’m not going to stand for any of this stuff.” But my mother didn’t do that. My mother raised us to be artists. She raised us to be creative people.

I have to reflect on what my mother learned about life to then have five Black children in whom she instilled the absolute foundational power of creativity. We were my mother’s children. I grew up in a two-parent household, but we were our mother’s. My father left the house and drove to Long Beach every day, there and back. So we didn’t see him a lot. We were hers, and she made us in her image.

She was also a genius. She could speak four languages, she could do all this stuff. But she didn’t put us on that path. I often reflect on how smart, wise my mother was, and what she knew about life. That the most important thing she could give us was the capacity to be creative and brave at the same time. I grew up feeling something magical happening to me when I would make things. Making our own clothes, my mother taught us to read the back of patterns. You would have to pick your fabric out, lay out the pattern. You’d cut your own back-to-school clothes. But something would always shift when we would enter into the process together. That creative industry in the house…. We got to know each other as siblings in a different way. But I also make a connection to that energy of this industrious creativity for your life. We were making clothes for your life. We were making a chair for your life.

My mother didn’t know if we would survive our childhood, and she wanted to give us the absolutely most important things that we would need for our whole life the whole time, which was to be creative and brave. My mother forced us to be brave when we were kids, and sometimes it was terrifying. My mother was violent. If we had an issue at school, we would have to go to the principal and speak up and she would come. We would have to go to the Los Angeles Board of Education and take those three minutes standing in front of all those adults and say, “This is what we need. This is how we feel.” We would have to go to protests: “U.S. out of El Salvador!”

My mother didn’t know if we would survive the world, and she gave us the tools that she felt that we would need to survive as early as she could, and just ran it over and over and over again. “Be creative and brave.” She would always say, “Figure it out. Figure it out. Figure it out. Figure it out.” I would watch on television these sorts of mainstream media representations of mothers who were doing so much for their kids. They were cooking and cleaning and doing all this stuff. My mother was like, “You cook it. This is how you cook. This is how you wash clothes.” Now, mind you, she had five of us. But we were never flimsy kids. We were never like, “Mommy, do this for us.” Partially because we were afraid of her, but also because she made sure we could take care of ourselves internally, in our hearts and in our minds.

I grew up in a house that had a big library in it, too. My mother taught us to read before we all went to school. I learned to read before preschool. There’s an old Los Angeles Times article with my mother homeschooling us in the sunroom of our house before we were enrolled in public school.

It keeps revealing itself to me, the power of imagination. I don’t go to the think tank and be like, “Oh, my God, what should we do about this? I got these neighbors, they’re crazy as hell. They barbed-wired this shit up.” I don’t do that. I work creatively inside myself to continually activate an ecosystem where I can be whole and safe. That’s what she gave us. She gave us the understanding that to be alive is to be creative.

When did collecting objects become a part of your creative process?

Without shame, I think it was after this whole [period of], “I’m going to die. I’m going to kill myself in six months. I’m going to see what happens, and I’m going to give myself full permission to do what feels right.” What really felt right was to pick up stuff off of the ground, to be in a vacant lot. It would make me feel high. I didn’t use cannabis until I was 40-something years old. Using that plant medicine is a feeling that is so similar, in my physiological body, to what it was like for me to pick up wood out of vacant lots. I felt that, somehow, the very best art supplies were these free scattered pieces of old houses. I felt like I was playing hooky on adulthood.

I would bring pieces of wood home. For a while, I would just look at the wood. It would sometimes make me feel like I was going to cry. I would be like, “I have this wood. That means anything is possible. I could build anything from this.” Before then, I felt like I had this different understanding of what it was to be an artist. It was a sort of “clean” thing sanctioned by…. My friend was a professor at Carnegie Mellon, and I visited this M.F.A. crit, and I spiraled into a depression after it. I was like, “Oh, this is a major institution, and they’re training people to be artists and to work in museums.” But the class fought with each other. People cried. Men cried. These were adults, and they cried and there was anger and they had to stop the class. I was like, “Shit, they’re training people to do what I think I want to do, but I’m not experiencing what they’re experiencing. I don’t understand why they’re so mean to each other. Is this a world that I can be in? Could I bear this kind of vitriol? Maybe I’m not an artist, if this is how they’re shaping people to be artists.” I stopped calling myself an artist because that did not align with what I saw, how the world was saying, “This is what art is.”

I had shame about the ways that I…. Man, I would drive by things on trash day, and I’d be like, “Oh, my God, that chair gives me such a feeling." Being a weird Black kid in an all-Black neighborhood, the amount of times people are like, “Are you doing voodoo?" That’s a real thing. It’s just this weird Black-people-collecting-stuff-is-voodoo thing.

Bill Clinton said that to me, too. Bill Clinton didn’t say it in a bad way. He was just like, “Me and Hillary went to Haiti for our wedding honeymoon, and I see your little voodoo dolls, vanessa. I saw those in Haiti, too."

Wait a second, when did you connect with Bill Clinton?

I was asked by Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art to speak before him at the [“Insights From a Changing America”] Summit [in 2014]. The White House gets in touch with you, and they say, “This is how you introduce a president.” There’s all this language. I had to memorize this thing. But I gave my talk before Bill Clinton gave the keynote. It was wild as hell. It was me in a room with Deepak Chopra, Maya Lin, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Quentin Tarantino. I go on stage, it’s the weakest clap, and I start giving my talk—and it became the most amazing talk. Somebody from the Secret Service came up to me in the green room, and they were like, “We’re going to need you to vamp. Just keep talking. Somebody will come into the room and hold up their hand. When this guy from the Secret Service holds up their hand, stop talking and introduce the president.”

So I’m giving the talk, it’s going great, a Secret Service guy comes in, holds up his hand, and then I see Bill Clinton come in, and I’m literally in the middle of a poem and I can’t just stop. So I finish the poem, and I’m like, “And welcoming the forty-second President of the United States of America, William Jefferson—” And I do it, but the audience is doing an ovation for me. President Clinton is walking down the aisle. He walks up to me, I step off the stage, and he has a speech in his hands. He looks at me and rolls it up and he goes, “Alice [Walton] has asked me to do a lot of difficult things in my life, but I don’t know if anything’s going to be as hard as following vanessa german."

Oh, wow.

Then I started to walk away to get water because it was so intense, and he goes, “You know, vanessa, Hillary and I went to Haiti on our honeymoon and I saw your little voodoo dolls in the collection.…” I was like, “Oh, you’re fucking kidding me. The president just did the voodoo-doll thing.” Then he said, “I was going to give this speech, but given everything you said, I can’t give this speech now. I’m just going to talk.” So he just talked, and he talked to me. He looked at me, and I stood and just looked at him. It’s on video—you can see it.

So, walking through the hood of Pittsburgh, I’d get Black church-y adults being like, “Aren’t you the carpet muncher who makes voodoo dolls?” I’d be like, “Aren’t you the Christian that’s supposed to love first?” But, whatever.

Shifting gears, writing and poetry are such a big part of your process. The titles of your artworks are practically poems unto themselves. How do you think about the role of poetry and language and words in your work?

I recognized early on in my practice that what you see in the object is a small percentage of the material. I wanted to find a way to include the invisible in the work, so I would put it in the media. Those first works, the works that literally brought me out of poverty—I was just squatting in a place—I recognized that while people would see that assemblage, what they didn’t know is that it had saved my life. What they didn’t know is that that taught me what love was. I have a living understanding and recognition for the technology of my own self of what love is. So it allowed me to bring the invisible and make it visible in the work. But it also allowed me to put things in the work that I was told to keep out of the work, because it would make mostly European white audiences uncomfortable. Things about anger and rage.

In my material descriptions, I would just include: “Oh, the police stopped me today.” It would be like, “Wood, fiber, blue pigment, the police stopped me today and threatened to handcuff me because I said something about the old man on the corner,” followed by “white paint.” I would just insert things that happened while the police killed somebody in the alleyway outside my studio. That’s in the material list, too, because it has impacted the ecosystem that then impacted the object.

To this day, I’ll talk about art and love and still have.... I had a talk at the McNay [Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas] a month ago. Last question in the Q&A was a white man telling me that he feels like my artwork is so angry, even though I just gave a talk about art and love. “Could you address the anger in your work?” he asked. The way that I have been confronted by mostly white men feeling threatened by anything racially or gender-related or confrontational in my work and that it doesn’t belong there! Don’t I want to be nice? Don’t I want to make pretty things? Don’t I want to make people happy? He was like, “Are you going to talk about this?” It was really upsetting to other people in the audience, but I didn’t want to have to negotiate my wholeness in the work.

In 2003, I was thinking about going to the Bush-Kerry election, and I wrote this poem [“The Patriot Act”]. I won this national slam poetry competition called “Slam Bush,” and I got to perform with The Roots. But people started to write me letters because that [poem] became public. People didn’t want me to have anything to say about America that wasn’t, “I’m so grateful to not be in Africa and to be in a civilized country.” “You should be more grateful about this.” “The Second Amendment exists so you can protect yourself.” I talked about guns and health care in it. One of the ways I found to not have to negotiate my experience as a Black person was to put it in the material list for my artworks, and then people can negotiate that themselves. I also wanted to make space for the reality that it’s not just physical. I want the work to be in a conversation about what it is to be human.

Considering and looking at your art, it strikes me that there’s so much thinking underlying it—your material list, for example—but then it’s also mostly about feeling. The thinking almost disappears.

I’m so glad you said that.

Your art speaks so simply and strongly in terms of the feeling embedded in it. I was hoping we would close this conversation by discussing this felt aspect of your work.

There was a major American curator—I’m not going to say their name. They were doing a studio visit with me, and I said it was really important to me to make space for people to feel. I said, “Feeling, I think, is the most important thing that we do as human beings.” And she goes, “Well, thinking is up there, too.” I said, “But do you realize that you feel about what you think?” This is a really academic person. She’s got a couple Ph.D.s. But I was like, “You feel these things.”

I started to language an experience I was having, what I call “an epidemic of feel-lessness.” There were all these sorts of major things that would happen to all of us culturally, and there would be this sort of immediate intellectual space made to process it, but not a space made for the expansiveness of feeling that can come with it. I even think about when Kobe Bryant died. I’ve had this feeling since I was a kid, this whole thing about people not publicly processing these deaths. Kobe Bryant was really special to me. I was in L.A., he was drafted, he was young, he was cute, he was Black. I expressed that, and people were DMing me, “Well, he was also a rapist.” [Editor’s note: In 2003, Bryant was accused of sexual assault by a 19-year-old hotel employee in Vail, Colorado. In the end, there was no verdict, and the case was dropped.] I was like, “We can also feel many different things.” This idea that you can only feel one thing for a certain amount of time and it might not even be okay for you to feel that….

I felt like I was in environments that were really compromised because there was all of this policing of feeling. Even the man at the McNay talk being like, “I feel like your work is really angry.” Then he said, “Are you angry?” I was just silent on the stage. We had just talked about love and children and creativity, and he wanted me to justify any anger that I’ve felt. He said, “Well, are you going to answer the question?” I said, “First thing I’m going to do is just let you see how beautiful I am,” and I walked back and forth at the foot of the stage. In my mind, what I wanted to ask him is: “Why is you asking ‘Are you angry?’ important?” I said, “I have anger when I’m angry. Don’t you have anger when you’re angry?” What was interesting to me is—and that he didn’t recognize—is the judgment that’s placed on anger. Anger is the emotional expression of injustice. Anger is a feeling, and it’s not actually a stopping place. We have so little cultural understanding about holding human emotions.

I became a hospice volunteer when I was 21 because I wanted to learn more about how we were doing death in our culture. I went through all this death training to be with people when they had a loved one that was dying. To me, it was so clear, all the shit that didn’t matter. It really was like, “I want you to be close to me.” I would see families going through the ravages of grief at the end of life. I had this one family who bought the largest bed that they could buy so they could all just sleep together with their loved one who was dying. They would all just get in the bed. All people wanted was the closeness. All they wanted, really, that they could identify, that mattered, was to be inside their love, loving. And that love was big enough to hold when people would freak the fuck out. And they would be angry: Why does this 9 year old have this weird fucking tumor? Why is he dying? But the love held. Love really is all we have.

Steve Jobs’s last fucking words before he died were, “Oh wow. Oh wow. Oh wow.” Reentering the human technology of holding feeling and being in a living relationship with wonder and love, that’s all we have. I don’t actually trust voting. I don’t trust the government. I don’t believe that there’s policy and legislation that’s going to bring us back to ourselves. Only we can do that. And we have to be able to feel where we are to be there.

I was just thinking of the Rilke quote “No feeling is final.”

Wasn’t Rilke so magical and wild with what came out of him? Yes. No feeling is final.