The Poetic, Humanistic Architecture of Lina Ghotmeh

As far as architecture career paths go, Lina Ghotmeh’s is a bit of an anomaly. In 2005, at age 25, while working in London with the firms Ateliers Jean Nouvel and Foster + Partners, she moonlighted with two other young architects, Dan Dorell and Tsuyoshi Tane, to swiftly put together a competition entry for the Estonian National Museum. To their surprise and delight, their proposal won. (The success led the three to form a firm, DGT Architects.) Most architects can only dream of such a project, and very few begin with a commission of that scale or stature: Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, with the Pompidou Center in Paris, completed in 1977 when they were 34 and 38, respectively, is one rare exception; Maya Lin, who won with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1981 when she was just 21, is another. Shortly after finishing construction in 2016, the 364,000-square-foot Estonian National Museum, with its elegant, gently sloping roof and radical, metaphorical form, received the Grand Prix Afex, a prestigious French architecture prize. Around that time—project complete—Dorell, Tane, and Ghotmeh shuttered DGT and each took off in new directions.

In the years since, Ghotmeh’s eponymous firm has flourished, with commissions ranging from an Hermès leather-goods workshop in Normandy; to a concrete apartment tower in Beirut (which landed on the October 2020 cover of Architectural Record); to a recently announced win, a contemporary art museum in AlUla, Saudi Arabia. She’s also the designer of this year’s Serpentine pavilion in London, the latest in a lineage of bold-faced architectural concepts that began in 2000 with the late Zaha Hadid and has also included architects such as Rem Koolhaas, Peter Zumthor, and Herzog & de Meuron. Ghotmeh has referred to her project, called “À table”—a French term that translates as sitting together, sharing a meal, and conversing—as “a bit Mary Poppins,” and she’s not wrong. Its whimsical, swooping structure and beautiful laminated timber form loosely references an umbrella or a carousel tent, but also the rib structure of a leaf, a nod to the neighboring Hyde Park tree canopies.

Here, Ghotmeh discusses her unusual career trajectory to date, her humble and focused vision for the Serpentine pavilion, and why she views herself as a “humanist architect.”

I want to begin by saying how fascinating it is that the slanted roof of your first project, the Estonian National Museum, built on a former Soviet military base, literally takes off from the ground of a runway, and that, since that project was completed in 2016, your career trajectory’s kind of been like that, too.

It’s been intense. Architecture is very intense, but I love it.

It’s somehow poetic. How do you look back on the impact of that museum on your career?

When I look back, starting this project at the age of 25, winning this competition, and really believing that this will be constructed was so important. Faith and the ambition of really wanting things to happen is so important in our practice as architects, sharing visions, trying to keep the dream [alive]. That’s possible when you’re very young and [you] believe that. Now, of course, I look at it, and it was like starting with the largest project in one’s career. [Most architects] work on smaller projects and wish to have a large project to end their career somehow. My career started with this.

There was also the fact that this museum is a human venture, because it was working with the then director of the National Estonian Museum [Tonis Lukas], learning how the architect is not only designing the project, that they’re also trying to share the vision, especially on a project that was so political, with the mayor and the city of Tartu—and with Estonians. Because there were some oppositions in the beginning around this project: It’s an emotionally charged airfield, and they thought it was almost like monumentalizing this history that was emotionally negative. But it was really transforming a heavily charged place into something positive.

The most touching part was how Estonians reappropriated that space. It became a cultural incubator for them. I did some interviews at the end, trying to get Estonians to say what the meaning of such a building was for them. It was touching to see how they actually never believed in the beginning that they could have their own museum, and how proud they were to be able to build their house. It’s not just a museum for them; it’s their house. It’s a place where they’re permanently constructing their culture.

It’s not lost on me, as you’re describing the collective aspect of this museum, that your Serpentine pavilion this summer embodies such a thing, too. The pavilion opens in ten days from when we’re having this conversation. Now that it’s nearing completion, how are you feeling about it? Could you speak to this cultural exchange element of it?

Actually, talking about the roof of the Estonian National Museum, now I’m thinking about the Serpentine [pavilion]. One of the elements of the Serpentine is this roof that’s floating, that’s bringing people together around the same place. The roof is the iconic part of the building, a pleated structure where everyone is invited to sit around the table. The bringing together of people starts with this moment of being under one roof together.

The planet is another roof. It’s a ground, but it’s also the same ground that we’re both on together. When we’re talking about collectiveness and togetherness, the Serpentine was also about bringing different fields of complexities and references into the same project. It’s not just a self-referential place. It enriches itself by referencing other things, other histories, other stories. For example, [it references] the toguna structure, which are these huts that are built by the Dogon people in Mali, where the elderly meet under one roof and discuss important matters. I was also thinking about forms like carousels that exist in parks, the memory of these.

The pavilion is also inspired by the rib structure of leaves, right?

Yes, we looked at foliage, but also the site itself, the environment and place where we’re intervening. It’s about The Serpentine and Hyde Park, and looking at the context of where we are—these amazing trees that are all around. Looking, also, at how to echo nature, what to build with, looking at the surrounding resources.

We were also looking at the structure of the roof itself. If you look at the pleats, they’re like tree leaves. With a leaf, you have this main structure, and then you have these secondary, smaller structures that hold the whole leaf and make it flexible. The roof is about that. It’s a really simple structure that starts with this cantilevering beam that creates the main pleats, and then you have the secondary structure, then raise the wall. The structure becomes the aesthetic of the pavilion itself.

I wanted to bring up materials. Because, why make a pavilion in 2023? The Serpentine has faced a backlash over the environmental impact of its pavilions in the past, and yours keeps this concern in mind: It’s made of laminated timber and recycled glass, and has bolted connections for easy disassembly. Can you explain how you chose and used these particular materials and design components?

Now, more and more, we have to be climate-aware. We have to bear our own responsibility and push our clients as much as possible to make it worth constructing, and to make it more like an act of symbiosis with our environment rather than an obstruction. Building a pavilion is essential, I think, because it’s also a time apart. It’s the possibility of having a place open for people, where art becomes much more accessible to everyone. What’s nice about the Serpentine pavilion is that it’s a place where people feel so at ease to really come in. Sometimes, people are more skeptical to get into galleries, because they feel it’s an elitist place. But in the pavilion they’re open. They get in and discover art.

Art should be a part of our daily life. Art is essential. It’s not a luxury. It really has this capacity of critical thinking. That’s why I feel like the pavilion is important.

Right. Your pavilion is not simply a frivolous architectural exercise. There’s meaning underlying it.

Yeah, it’s important to have these places where the program is open, where people can stroll, where people can discover architecture and think of the importance of architecture in our life. I was thinking about how to construct in the most sustainable way possible. The pavilion is built with a lightweight material: wood. I was also thinking about having the least [possible] foundation construction on the site. Because it’s wood, because it’s a modular system, the foundation is really minimal and it’s all reusable.

I was on-site last week, and when I stopped by, they went very fast in the construction. They were telling me that this is the easiest construction because we remove very little earth from the place. And the fact that it’s modular allows the least manufacturing of elements.

What does it mean to you to be a part of this ongoing Serpentine pavilion legacy and dialogue that began with Zaha Hadid and most recently continued with Theaster Gates?

It’s building history. It’s a place that allows for dialogue with a larger public. That’s beautiful because it’s bridging and creating architectural culture. That’s very important to our profession. Architects, unfortunately, still build very little in the cityscape or builtscape. We have to have a bigger impact. Most of our builtscape is mass-produced and built by non-architects. The pavilion brings the joy of architecture to a larger audience. With this commission, there’s a preciousness and a responsibility to reflect the times in which we build and also to connect with people.

It makes me feel this responsibility that it has to be worthwhile. I’m doing my best. Let’s see.

Shifting gears a bit, I was reading that during the Venice Architecture Biennale you just announced that you’re designing a contemporary art museum at AlUla in northwestern Saudi Arabia.

Yeah, I’ve been invited a few times to travel to AlUla, and then discovered this place. I grew up in Beirut and Lebanon, and in Arab culture, of course. I’ve always known a lot about the community living in Saudi Arabia. AlUla was very ambiguous for me, though: What’s this? The place, the desert…. I was very curious to discover the country. Of course [I thought], as a woman, how am I going to visit there?

I was very surprised when I arrived in Riyadh, and meeting the people in AlUla and these fantastic places that embody the long history of our civilization—the Nabataeans who were carving their tombs inside these rocks, and the Incense Road, with all the trade that was passing through. Also, the richness of the desert, with its multiple facets, the colors. And the community—I met with the local community there in the oasis, their closeness to agriculture.

And the kids—education, for me, is primal in this context. Because I had to do this competition, I went to visit the kids’ school there, just on a personal initiative, to meet with them and ask, “What is a museum? What does building a museum in this context mean for you?” It was really fantastic to see how mature they were and how they saw this place as extraordinary. Some of them were saying a museum has to be a place where we’re able to re-see our daily lives in a different way. Some of them were 6 years old, saying it’s a place for the bones of dinosaurs. [Laughs]

For me, it’s really a fantastic context and culture to rethink what a museum can be, how it could play a role in building change and developing critical thinking and making a place as an incubator of culture, of thought, of questions. As an architect, that gives my role a lot of meaning.

The politics, not to mention ethics, around working in Saudi Arabia is complicated, but your visit sounds like it was reassuring.

Yes, I think it’s very important to know where to intervene, and to know not to intervene in a faraway way. I believe that when one is asked to work in a context, you cannot just grow something in an alien context. One needs to understand: Who are you building with? Is this meaningful enough? Dialogue is important, and also building on positives, because there’s a lot of injustice all over the world. We have to be vessels of change and of building more justice, rather than enclosing ourselves.

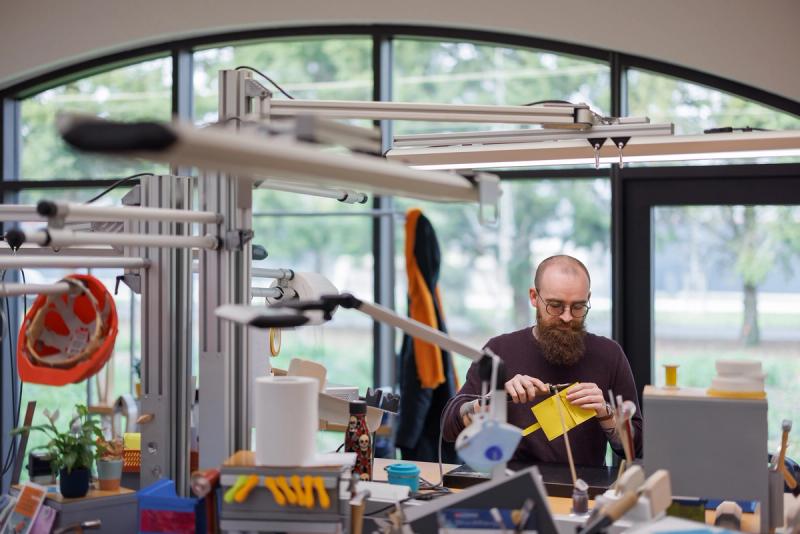

You recently completed a leather goods workshop for Hermès. To construct it, you worked with a local brickyard that produced more than five-hundred thousand bricks using traditional methods. Tell me about that process.

It was a competition that Hermès invited me to be a part of. They wanted to build an ecologically ambitious manufacture. They are pioneers in instilling [ecological and sustainable] values in their projects. What was very specific about this commission is that, normally, industrial places have very “anonymous” architecture—metal tins, handguards, or glass boxes. I find that a pity, because the site itself is fantastic, with these beautiful hills and landscapes there, although it’s surrounded closely by these sorts of industrial buildings.

For me, it was important to reconnect the building with its more inherent nature, somehow getting away from the stigma of what an industrial building could be and building a structure that could be at once a museum, an industrial building, and a house. It could be any function because it has its own dignity.

The project brought me to research who Hermès is, how they started with the horse saddleries and different products that they developed, and their value of the hand and the work of the hand. It was also about looking at the resources of Normandy. It’s a damp, wet ground, and very claylike. One of the materials that is very much present there is the brick construction in Louviers. These artisans and brickmakers are now losing jobs because they are either being competed with the industrial brickmakers, or because they’re only working on renovations and not on new construction. I thought it was really nice to go back to this scale of the hand with a brick, echoing the craft of Hermès, working with artisans and brickmakers to manufacture these bricks locally.

Of course, the materials are not only brick. The ceiling is made out of wood—we were trying to calculate the carbon footprint of the wood. All of the insulation materials were bio-sourced and calculated in terms of carbon footprint. Somehow, all of this intertwined to create the holistic approach of how the building would look.

The carbon footprint of the construction industry is staggering. It’s something you’ve been really outspoken about.

It’s forty percent of our impact!

Why don’t you think there are more developers, architects, and companies using local materials or reusing existing buildings and materials more often? Do you think a shift is possible? The Hermès project is an interesting example of how it can be.

When we’re talking about forty percent, I think one also has to consider the responsibility of architects and the role we play in this. Unfortunately, not a lot of what gets built is by architects. We don’t get to apply our knowledge and struggle and push our clients further. That’s one issue.

Second, the building industry and regulations are constructed in a very specific way today, and it’s all driven by insurance. In the Hermès project, we were able to push this. With Hermès, I had a client who has the same ambition I have. I even pushed it further than their own ambition, and they took the lead with me. We pushed it.

Sometimes, on other projects—for example, we had renovation, and for this competition I proposed, instead of throwing all of the cladding off the façade, just taking out the cladding, bringing it again to the manufacturer, repurposing it, and just changing color and shape, and then reusing it…. The client was afraid because of the insurance. They were afraid of the regulation. We have to re-question the regulation again.

The regulatory and insurance frameworks are still quite complex. These have to be changed faster. The standard materials that are available on the market are not enough yet to give us the lead to change, and not enough common materials are accessible or able to use them for all types of housing. Of course, today, sometimes it’s more expensive when you’re using fiber or bio-sourced wood insulation than regular insulation, so we need to invest and think about where the value actually is. Sometimes, if you invest more, but you’re putting more value into what you’re building, in the long run, you’ll need less maintenance, you’ll need less energy, your carbon price will be lower.

On your website, you describe yourself as a “humanist architect.”

It was a journalist [the art historian Christine Blanchet] who wrote that.

Well, I was intrigued by it. I was wondering, how do you think about that word, humanist?

I’ve been constantly thinking about it since I put [the phrase] on the website. It drives me, always, to think about architecture in a relational way, to think about our links together, and to think about and respect the living.

Today, even more than just building our relationship together as a humanity, being a humanist is also about building a relationship to the living in a general way, respecting the living environment. Being a humanist is not thinking about an act of architecture as an egocentric act of building, a signal somewhere, or an object dropped in. It’s more thinking about this act of emerging and making meaning through architecture. Sometimes, it’s more tedious to do this because you need to think about where the dialogue occurs and how the building is able to disappear at some point in its context and be appropriated. But it’s more rewarding. It brings people to love the places and to have pleasure with architecture.

So much of your work takes historical references to forge a deep sense of place—built poetry, in my opinion.

I love poetry. We’re not only rational beings. I love poetry, beauty, pleasure, joy, emotions. These things are not taboo.

Do you consider yourself a poet?

I don’t know if I’m a poet, but maybe I have this kind of romantic approach. When I visited Mexico City recently, I went to visit the Luis Barragán Capuchin [Convent] Chapel for the first time. It was so fantastic. It had been a while since I’d had this kind of emotion from architecture. I just started crying. The colors and lights, the stained glass—the materiality gives you a sense of presence. At the same time, you’re completely transported somewhere else. The volumes! It’s powerful. I like bringing in this capacity of sensitivity to our environment.

You were raised in Beirut and studied at the American University of Beirut, where memory played a core part of your work. There you formed an “archeology of the future” methodology. Could you explain this approach? Would you say this is still your overarching philosophy today?

Yes, I think so. The studies at the American University of Beirut really affected me, and also the professors there…. I did my first studies at a French school, and then I started architecture at the American University of Beirut. It was a completely different system, a campus where there were multiple disciplines. I started some courses in biology, political science, and anthropology, and then in architecture.

I learned critical thinking there, to open your mind and, before you do anything, try to look around and research and explain why you’re doing what you’re doing. “Because I dreamt about it yesterday” doesn’t work. My work became more discursive and investigatory.

I had a small studio space there where I spent five years, day and night. The space became like an investigation. I had pictures, drawings, and paintings that I hung in the space. It was almost a detective space. I was looking at the context where I grew up, with these archeologies and scenes of buildings that were completely destroyed. This phrase “archeology of the future” emerged. Today, it resonates. I feel that many of us are interested in this relationship to our ancestors, to what we’ve built before, and to learning from Indigenous architecture, relating to our environment in a much more sensitive way, to learn to build our future.

This makes me think of an unrealized project of yours, the 2012 proposal for the National Stadium of Japan from your DGT years, this incredible earth mound in the center of Tokyo. When it comes to thinking about nature, but also mankind’s building of monuments, you came to this ingenious solution: a monumental park in the middle of the city. It reminds me a bit of what Isamu Noguchi did with Moerenuma Park in Hokkaido, Japan.

Yeah, of course, and it’s also kind of echoing kofuns, these traditional mounds, where we used to bury the dead. It was about transforming the stadium into a place for people, not just as a building that stays unused most of that time. In that sense, it continues the park, and it offers something to the city again, rather than just taking something from the city.

You founded your own practice in 2016, and one of your first projects was the Stone Garden tower, located near the industrial port of Beirut. Shortly after its completion in 2020, there was a port explosion that destroyed a large part of the city, yet the building sustained relatively minor damage. Can you share a bit about that moment, that day, and the aftermath, and how it felt for you to have built such a resilient structure?

It was a very weird moment. I completely lost any sense of time. I was in Beirut. I’d arrived the day before. I had a bad feeling about the situation. It was somehow like reliving the history of how I grew up in the war, the moments of going down in the basement, the sounds. You don’t know what’s happening. It was really terrible. Your first reaction is: How’s the family? How is everyone doing? A kind of suspension in time happens.

As an architect, I was thinking, What happened to this building? I had just delivered it at that point. The façade was done by experiment. It’s handwork. There was always the risk that it would just fall off with this destruction. I went the next day, and it was a bit magical. The whole envelope was still standing, almost unmoved. Of course, all of the metals inside were distorted, all the lifts and doors—wherever the explosion could enter—it was completely shattered.

It was a moment of hope. It wasn’t as destructed as [what was around it].

What I find so beautiful is that Stone Garden was built as a testament to the city’s strength, and then it literally survives this blast.

People were taking it as a symbol for that, trying to build hope around persistence, even if resilience is a big question in such a context, too.

Another project I wanted to bring up, from 2019, is the invitation you had from the Okura Hotel and the architect Yoshio Taniguchi. What you created there was such a subtle and sophisticated integration, if I can call it that. What was it like for you to be in conversation with this incredible piece of midcentury architecture?

I met Yoshio Taniguchi at a dinner in Tokyo. He’s a really beautiful person, 85 years old, and with such humility, but also a masterful capacity. The Okura is all about proportions. When you look at some of his projects, like the Kanazawa museum [the Yoshiro and Yoshio Taniguchi Museum of Architecture], it’s really about how to draw the right proportions. If you change just a small proportion, it changes the whole thing. It’s just about these very fine lines.

He was doing the renovation of the Okura on the same footprint as his father had. He asked me to do this intervention because there was a French restaurant, and he wanted something that embodied French panache. I started thinking about this installation, how to develop something that echoes the wisteria flower, because that’s also the symbol of the Okura Hotel.

When I finished the project, that’s when I discovered that it’s a very important place. I knew about the Okura Hotel, but after finishing my project, the reaction was, “Oh, how come you designed something in this [iconic] Japanese place?” I was the foreigner working in a very exclusive place. They accepted me, in a certain way, even if it was about Japanese culture.

Last question: You’re the co-president of the RST Arches scientific network for architecture in extreme climates. Looking at our situation here on Earth, over the past three decades, it’s become clearer and clearer that the world is heating up. What are some of your greatest climate concerns, and how are you thinking about tackling them through architecture and construction systems?

RST Arches is experimenting on work about extreme environments—other planets. I’m less of a believer in building somewhere else. We have enough trouble here. We have to resolve the problems that we’ve made before we live somewhere else. But I’m interested in extreme environments and how we adapt, how we build more resilient architecture.

Learning how we’ve built in the past is a good way forward. When you think about how we, as humans, were less sedentary, we were more nomads in the past. We were constantly moving. We were less anchored in property or in ownership. Sometimes it seems to me that this is the future. We will have to adapt. We will be migrating much more, moving from one place to the other much more because of the [climate] disasters that will happen. Somehow we are bound to be nomads, to be more like how we were in the past, and as our ancestors were. So the question is, how do we make an architecture that also is less about ownership, and more about sharing, more about having transience in the way we live?