The Alchemy of David Adjaye’s Architecture

Ever since the Ghanaian British architect David Adjaye and I first met, in 2011, in large part because of our many intersecting interests, we have forged what I consider to be my longest-running interview: a kaleidoscopic series of conversations, probably numbering around 30 or so and spanning 12 years, about life and death, cities, architecture, landscape, art, light and shadow, the built environment, “luxury,” nature, culture, memory and memorials, Japan (particularly Kyoto and the Katsura Imperial Villa), Isamu Noguchi, racial politics, Blackness, the African diaspora, slavery, colonialism, trauma, the climate crisis, and so much else. Extending out of this dialogue, David wrote a beautiful foreword to my book In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials (Phaidon, 2020).

Along the way, in late 2018, during an interview for Town & Country magazine, in Miami’s Design District, David mentioned the notion of alchemy to me for the first time, describing how certain material junctions can form “an alchemic power.” Almost immediately, I thought, Alchemy should be the title of a book about how David chooses, uses, and combines materials, and the architecture that results. That book, Alchemy: The Material World of David Adjaye (Phaidon), is out this week.

Here, in an interview recorded when we began the project in earnest, in the summer of 2020, we discuss our respective definitions of the word alchemy, his approaches toward choosing and using materials, and why he doesn’t feel ready to talk about the spiritual or sacred nature of his buildings just yet.

Spencer Bailey: Let’s unpack the word alchemy.

David Adjaye: Why don’t you start by defining it?

SB: In my mind, it’s basically when materials combine to create a sort of magic—when something larger than the materials results.

DA: I would say, for me, alchemy is the art of transformation, to change one state into another.

SB: We talked a bit about this when we did that Town and Country interview, but how does this alchemy idea manifest itself in your work?

DA: Almost from day one, what was interesting for me was the potential of how the built environment has been industrialized. This inheritance of industrialized materials and preindustrialized materials creates an opportunity, as an architect, to no longer think in any singular way. It creates the opportunity to understand how to negotiate the presence and meaning of each of these conditions, and how to use those as a kind of encyclopedia. Or as a field that now has the opportunity for new combinations and new relationships, both traditional and technical, manufactured or not manufactured, to somehow create a newness or a new way of seeing. I’m super fascinated by that. My entire practice is about the negotiation of meanings and re-meanings of material.

SB: Expanding out a bit, how do you view alchemy from an urban-design perspective?

DA: The projects that have always profoundly affected me have a kind of alchemic effect in the sense that they radically transform, through an assemblage of material or materials, a reading of place, a reading of atmosphere, a reading of inclusivity or exclusivity. The trick for me has been recognizing this potential of the power of architecture when it comes together. Its transformatory power—its alchemic power—is to then see how one is not just waiting for that moment, but how one is able to work with that at every opportunity. How do you not wait for the moment of magic, but make the magic happen every single time?

SB: Science, of course, also underlies alchemy. What do you think about this junction of science and art? In architecture, where do the two fields meet?

DA: I’m pre-Copernicus. I have no separation of science and art. I find them equally creative and equally aligned. I have no sense that somehow one is logical and one is intuitive. It seems absurd to split these two things. Both are intuitive, both are creative, both are logical, both are methodological. I’m afraid I’m one of those people that doesn’t see any difference between this at all, even though I know there’s a huge history of this rupture. I just missed it somehow.

SB: Tactility—and connected to that, an engagement of all of the senses—is also central to alchemy. Your work does that. At every project I’ve visited of yours I’ve always felt this dynamic relationship to the body, where it’s not just about what you’re seeing; it’s about the bodily relationship to space.

DA: The body is essentially a sensing organ. It’s a mediator of some internal energy and external phenomenology. I’m obsessed with this idea that the body is able to sense things that are beyond sight, and can feel things beyond sight, and that science is just trying to work out what the words might be. But it’s real. When I go to an amazing place, I have feelings that I can’t even start to describe in terms of logic. They become supernatural. I’m always interested in this idea of supernatural feelings, that somehow there’s something more than is understood naturally.

Logic, for me, is a beautiful system of negotiating, but it’s not the only system. It’s one methodology. I’m interested in testing how to awaken the senses of the other characters in the arsenal of [human] sensing. It may be a little bit cheeky of me, but I’m obsessed with this idea.

I’m continually interested in that awakening in people. And why am I interested in that? Because I’m interested in that idea that there’s a sense of a supernatural self that has a kind of compass that’s about a civilization and a history and a story which is shared and collective and magnificent. That’s probably the most articulate way I’ve ever explained it. [Laughs]

SB: Good thing we’re recording. [Laughs]

Well, that got me thinking about the spiritual nature of your work—not necessarily in a literal sense, but in this larger metaphorical sense. It’s not so surprising that you’ve been chosen to design major spiritual spaces [such as the Abrahamic Family House in Abu Dhabi and the National Cathedral of Ghana].

DA: I’ve been busted! [Laughs]

SB: Could you talk about the spiritual nature of your work?

DA: I don’t know if I’m ready to do that yet. I’ll have to be at least 60 before I can talk about my spirituality.

SB: Okay, but phrased differently—

DA: I will talk about the common collective.

SB: The idea of the sacred, too. Can you touch on that?

DA: Hmm. When I’m 60. [Laughs] It’s a slow process. It’s like wine. It needs to mature before you can open the bottle.

I want to use my words right now very precisely. I’m searching for a collective sense of ourselves. I’m searching for a way in which we can reach past what we see in ourselves and to see something that unifies us as human beings on this planet.

I like the fact that my work is different from other people’s work. A lot of folks think, Well, I don’t know what the references are. I don’t know what you’re doing. I like the fact that it’s outside of the language that’s controlling the message of how architecture is. Some people just discard it. They’re like, “Oh, I don’t know, it doesn’t quite fit the whatever.…” What I want is for the work to create a kind of translation or a transformation. I’m profoundly interested in using architecture as a way to dissolve barriers.

SB: Could you talk a bit about not just how you choose materials, but also how you use materials?

DA: Yes. I’m almost convinced that any rule that says you can’t do something means that it’s something you can do. When somebody says, “This is anathema,” I’m like, “Ooh, interesting….”

When I started making black spaces, people thought I was crazy. And when everybody was obsessed with deconstructivist or Modernist windows, I went into ornament. But when I’m talking about ornaments, I’m not talking about decoration. I’m talking about the cause—light—and effect, and talking about it very scientifically. I’m talking about methods of mathematically cutting light into darkness, and creating spectral effects that engage emotions out of the body and activate sensations within people.

I know I’ve gone a little bit wide here, but I hope you understand that I deeply, instinctively believe that we all collectively share certain hardwiring. The city has coded us to just look and read things a certain way, but we’re able to activate much more because we’ve experienced so much as the species has evolved on this thing we call a planet, which has itself evolved. There’s much more complexity in us than we think.

If you look at my work, I’m obsessed with mimicking what the planet does. I’m in praise of what I call the “supernatural power” of the planet: the way it creates alchemic color, spectral effects, atmosphere; the way it creates compression moments; the way it creates lightness and weight.

SB: In the context of architecture—and in the context of your own work—how do you think about language and poetry? In asking this, I don’t want to get hyperbolic and say, “Oh, your work is so poetic, David.”

DA: Don’t make me throw up. [Laughs]

SB: I do feel like that there’s an underlying quality to your work, though, that really has to do with elements of what might be called poetry.

DA: I would take that.

SB: It’s a fine line to toe.

DA: I love poetry as a creative construct. I don’t read poetry, so I’m not one of those that’s going to recite [Geoffrey] Chaucer to you. But I’m interested, deeply, in the construction of poetry. My understanding of the construction of poetry is that it assembles and disassembles the meaning of words into new emotions and conditions that throw you into new translations that you just can’t get from narrative. I deeply love that aspect of poetry. You can say the work is obsessed with this idea of constructing to get you past the language. But I don’t take inspiration, literally, from poets.

I’m interested in the poetic effect of Basquiat or the poetic effect of Miles Davis. Or Mozart. But also I’m very interested in how it manifests in the world from an acoustic to a material composition.

SB: In how architecture becomes visceral.

DA: I always feel like my buildings are journeys. When I say “journey,” I mean it. I feel like everything is a journey: What’s the metaphor of the thing? What’s the composition of that journey? What does that journey do?

In projects where there isn’t an overly social or collective agenda, it sometimes comes out in a very personal dialogue with a client who I really enjoy and who enjoys me. For instance, in Silverlight, which I did for an amazing couple, it became a dialogue between us. They allowed me to expand a series of compositions that I would mostly do in public buildings, but somehow it appeared in their house. They pushed me to want to explore with them the potential of all these material and light effects.

Each project is this testing of a series of conditions, and each really has also been a honing of my skills in being able to put together certain compositions. My houses have been used mostly as places to test specific conditions, but also absolutely solve the baseline of what the client wants. This has allowed me to gain confidence when I’m working on a bigger scale.

SB: I wanted to bring up the role of memory here. What makes buildings, in your mind, memorable or meaningful or enriching?

DA: When they trigger that sense of being more than what you feel in your everyday life. That feeling that you get when a building activates another part of your mind or your sensing apparatus. It triggers either emotions or memories or conditions that really start to bring you into a kind of mood.

I can remember the emotion of seeing the pyramids for the first time as a young boy, and being utterly, jaw-droppingly like, “What the—!” It blew my mind. It was like pow. I remember thinking, Can anything ever pass this? I don’t think anything ever has, actually. It transforms your sense of yourself in your own body, being in a space so magical.

SB: Could you talk about architectural materials as a means toward creativity and pleasure? Materials can become a tool for promoting something that’s beyond the building itself.

DA: Absolutely. Materials for pleasure is a profound thing. Ultimately, one of the sensations of this effect is a pleasure from the physicality of things. Our sentient ability to gain pleasure from the assemblage of things may somehow be a little bit hocus-pocus, but it’s real, the way we have a pleasurable attraction to a composition.

I know when I look at, let’s say, a [Carlo] Scarpa moment, I’ll see one little element of a project—a material composition that he makes, or a compression—and it activates an entire investigation in me about something else. Or it might be an Oscar Niemeyer moment, where he endlessly does something that you just can’t believe could become so endless, and it expands another way—another infinity—that you want to create. Or seeing some detail that Eduardo Souto de Moura did on a building that nobody understands. Eduardo calls it “the joke.” He believes every architecture project has to have a joke. “If it doesn’t have a joke, he’s not a creator,” is what Eduardo used to always say to me. I know exactly what he means, and it’s not even about jokes; it’s about understanding exactly what it is you’re handling.

SB: This connects back to that poetry notion we were talking about.

DA: Voilà! Actually, Eduardo loves poetry and reads [Fernando] Pessoa. He can recite it to you.

SB: If we’re talking about alchemy, we also have to talk about the junction of light and shadow. Some of the most visceral responses I’ve ever had to buildings, including some of yours, have been when the light hits them in a certain way, or when a shadow falls, or you notice some sort of detail through the play of light. Can you explain this in understandable terms?

DA: I don’t know what else to say. [Laughs]

SB: Put differently, how do you approach the art and science of light and shadow?

DA: In the early work, it was very Disney—maybe Disney is the wrong word for this, but it was rudimentary, just models and light effects. I remember in my early projects, like the Sunken House or the Elektra House, playing with light bulbs and making physical models and really simulating effects and going, “Oh, my God, do you see how that’s working? Imagine twelve hours of that. That’s going to be incredible. That aperture has to be like that.” This was just before we were able to map everything with computers.

By the time I got to [the Museum of Contemporary Art] Denver in 2007, the technology had become so sophisticated that I could actually download the data of the sunlight in that particular one-mile zone for, whatever it was, a hundred years. I was then able to literally understand what I was doing with light effects. I simulated exactly what the conditions were going to be, and of course I can’t simulate every second of that, but I can simulate every hour of that, knowing that I can understand exactly what the effects are.

Doing that downloaded a ton of information into me that I now almost intuitively know—that if I do this, it will do that. It’s now so intuitive that I don’t even talk about it because I just know exactly what it’s going to do. People think you’re a magician, but it’s actually just a little bit of practice.

SB: Has your material selection process changed over the years?

DA: Continually. I don’t have a benchmark. Some people say, “Well, it’s got to be that stone.” For me, that can never be the case. “How does it look here? What does it do?” is how I always select materials. I never select materials from what it is. I select the nature of it. That’s the critical thing. After that, how it’s then manipulated, what opacity, what elasticity, what kind of texture is all through the lens of the place.

So how do I choose materials? I just choose. I go to a place, I sense it with my body and everything I have in me, and I say, “This is going to be about this.” I don’t know why. Well, I do know why, but I’m not going to tell you. [Laughs] That becomes the genesis of what the thing is meant to be. Once you move past looking at materials just as performance, you have an incredible opportunity to understand the beauty and the magic—or the alchemy, to use that term—of materials. I think that alchemy is really an ability to understand, what is the thing that is making me choose a material? I’m thinking about what has been nullified and what needs to be awoken.

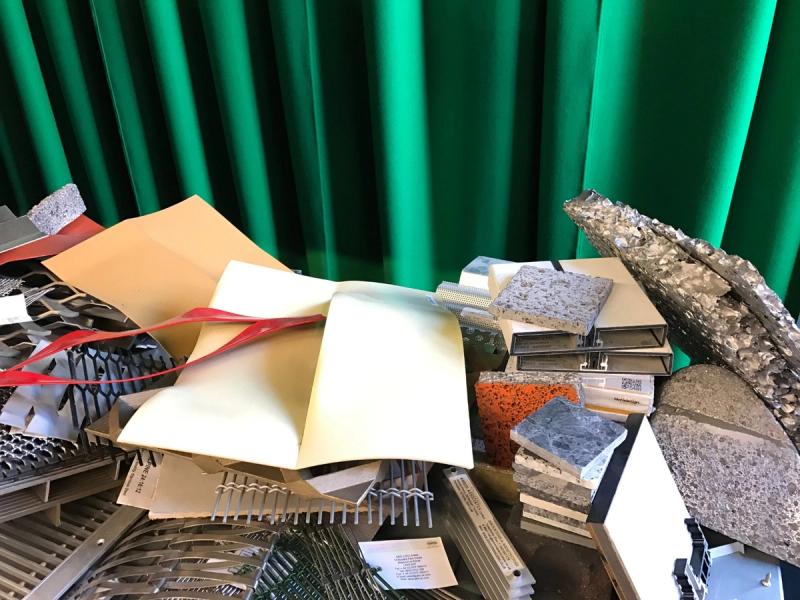

SB: I remember when I walked into your London studio [in 2017] and there was this huge, disorganized pile of materials at the entrance. I have a photo I took of it. I’ve never gotten it out of my head, this amazing, beautiful mess of materials. There was incredible order in the disorder. There seems to be a highly specific material makeup within this wide selection.

DA: One thing to definitely misunderstand is that it’s not whimsical. It’s deliberate and about a certain effect.

SB: That’s one of the things I wanted to touch on: the psychological impact of the materials you use.

DA: Oof. Here we go, Freud. [Laughs]

DB: Well, there’s this fast-emerging field called neuroaesthetics. I think that your work carries this emotional and psychological power. A social power, too. But I was wondering if you could speak to the psychological and emotional power of materials, this idea of the overwhelming feeling one can get from a material being used in a particular way.

DA: There’s no doubt about it that once you understand the effects and power of making form, you realize that you’re also manipulating a psychological dimension in the process. And that the combinations of certain materials—artists understand this really well—can be used to powerful effect. You’re able to use that material to either shepherd or distract a perception profoundly.

The psychological effects—or psychological power—of materiality is at the heart of the game of putting together materials. Essentially, it’s about psychologically trying to construct, in society, certain commonalities. That’s what I mean by the sensation of collective awareness. That’s a psychic thing. It’s an individual reading, but it’s a mental leap into that space. Material also has this ability to become the canvas that projects back at us things that we’re projecting onto it.

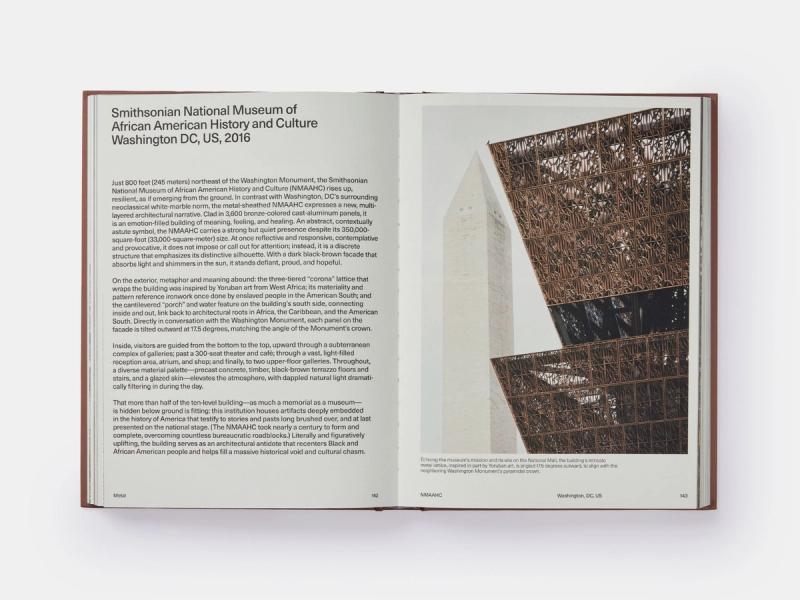

SB: As you were saying that, I was just thinking about my experiences at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and coming up from the dimly lit lower galleries and into the light-filled atrium.…

DA: I think that any good architect is a master of that psychology of materiality.

SB: Switching gears, I did want to bring up wabi-sabi, because I was just reading the book by Leonard Koren—

DA: I’ve not read it yet.

SB: I was like, “Holy shit, much of this is David’s work!” I know you have a Japan connection—your year in Kyoto during your studies at the Royal College of Art in the early nineties—but there’s a deeper connection to wabi-sabi, which is about roughness, material combinations, darkness, texture.…

DA: Voilà.

SB: I was wondering if you could speak to this roughness dimension, too, the idea of materials being something that aren’t necessarily polished or perfect, but almost intentionally imperfect.

DA: Intentional imperfection is an art form. I remember talking to Peter Zumthor when he came to see my Idea Store [in Whitechapel]. He said, “How can you accept this concrete?” I was like, “Because it’s beautiful.” He was utterly shocked, because it was shoddy work. I was like, “And there we have it. That’s why I go on this road and you go on that road.”

I mean, call it wabi-sabi. It’s interesting: Japan was very important to me because Japan made me let go of the value of what you think things are, and that was about really looking at Buddhist shrines and looking at concepts such as wabi-sabi. While there I saw a profound re-meaning of material within culture: what was considered to be “primitivism” in the West was there transformed into the most significant and sophisticated materials in the world. Earth, mud, sticks, thatch, and a few rocks amalgamated into an architecture that connected to the cosmos and revealed unseen interconnectivity between people and place.

Japan also allowed me to go back to Africa and really understand and look at animism and the effects of animism, because of the animist culture of the continent.

SB: It’s the idea that there’s an energy embedded in everything, right?

DA: In everything. And that form is about these contrasts—that to perceive form you have to create the right combination of contrasts, and that there is no such thing as too much or too little; there’s just combinations.

SB: It’s interesting that you mentioned Peter Zumthor because I recently read his book Atmospheres, based on a lecture he once gave, and while your work differs from his in many ways, I would say that the ideas in Atmospheres are deeply connected to your practice. Could you talk about atmosphere in relation to materiality and alchemy?

DA: There are very few moments in the world—and language sometimes can do it—where you can create collective agency and connection. Atmosphere is a moment when a collection of people—beings—engage in a singular experience from their own perspective, but somehow unified in that perception. It comes from the ability of sculpture or architecture to create compositions that really have this effect. It’s a kind of transformative effect. I think that’s what Zumthor also means by “atmosphere.”

SB: Could you speak to the social aspect of how you view materials? As a means for creating connections, for uplifting people, and helping knit together the social fabric of a place.…

DA: I’ve always been fascinated with seeing if I could move the discourse of materials beyond their performance and constructability and into the social realm: what a material is and how it profoundly affects human beings. It goes back to a deep feeling about the impact of material environments on humans: a forest, a cave, an earth structure. It’s deeply wired in our psyches.

SB: The notion of “climate moderation,” which we’ve talked about before, is also at play here.

DA: Peter Smithson was my teacher. I completely believe in climate moderators.

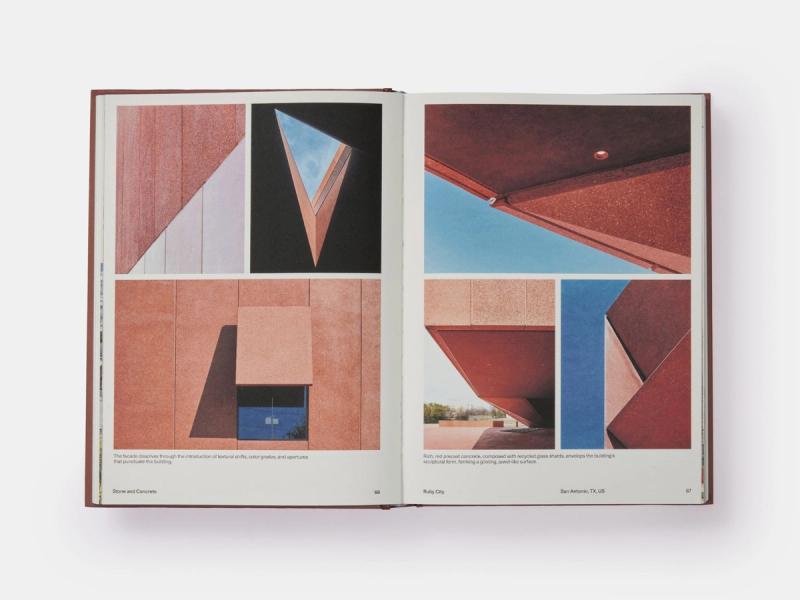

SB: As a climate moderator yourself, how do you determine the materials you choose, based on the climate of a place? Why, for example, the red-patterned metal façade for the Aïshti Foundation in Beirut?

DA: The red of Beirut…. To get that commission was really extraordinary. I never thought I’d work in Beirut. I happened to have spent a short time growing up in Beirut. It had a very large impact on me because it was just before the war. I remember being a young child sitting on the balcony, hearing the rumble of a column of tanks rolling in from Jordan. If you’ve ever heard that in your life, you will never forget it, because it’s like an earthquake. I heard shelling. I remember my father coming home that day and saying, “We’re leaving immediately.”

Beirut comes back to me in fragments. I went to the international school there. Beirut was this incredible place in the Middle East that was supposed to be super developed, super sophisticated. It was marked by these red terra-cotta roofs. When my father was alive, when he talked about Beirut, it was the red roofs of Beirut and the art deco part of the city. Well, that’s all gone now because of development. There are hardly any red roofs left.

When I did the project, I talked to the client [Tony Salamé] and said [of the ornamental red aluminum façade], “This is really funny, this little ‘joke.’” For my father’s generation, Bierut was all about the red roofs, and for me, it’s a concrete jungle. But for me, it’s also about the sea, and this memory of Beirut being the city along the sea….

SB: I’ve always felt that Goethe’s “Architecture is frozen music” quote is false, but I do think that there’s a beautiful rhythm to your buildings, including at Aïshti and the Ideas Stores.

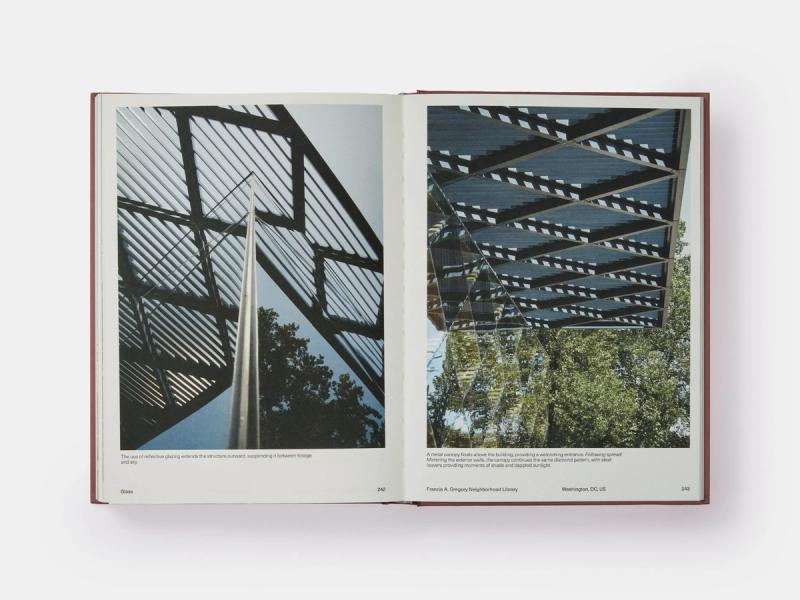

DA: Rhythm is deeply embedded in the work. It’s a recognition of forms, proportions, and systems that are not Eurocentric. It’s the clue to understanding how my work connects to other knowledge systems in the world, specifically African knowledge systems. If you look at my libraries [the Idea Stores on Whitechapel Road and Chrisp Street in London, as well as the Francis A. Gregory Library and William O. Lockridge / Bellevue Library in Washington, D.C.], you’ll know that I’m steeply and deeply embedded in those rhythmic systems. When I say something is beautiful, I’m acknowledging a similar relationship to a body of knowledge. It looks surprising to people who don’t look at that, but anybody who does will see it very very clearly.

For me, when people ask, “How is your work African?” I always laugh and think, Well, clearly you don’t have eyes, because you can’t see what’s so blatantly in front of you. My compositions and the way I work—and the forms, even the tonalities—are all about a different knowledge. That’s what you’re calling rhythmic. It’s the relationship to Africa. That form happens in sound, it happens in form, it happens in material. If we’re going to talk about alchemy, we have to talk about Africa.

SB: Great, let’s. How do you view alchemy in the context of Africa and the diaspora?

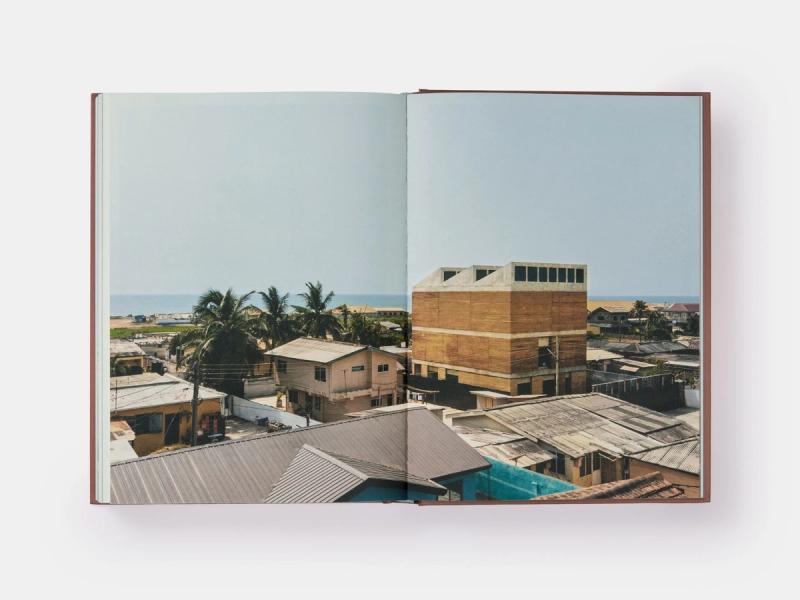

DA: Alchemy, in the context of Africa, is very normal. It’s part of the way in which creativity operates. It seems unusual in the West, because it’s not the normal way in which it happens—it’s much more logical and organized [here]. Whereas the notion of transformation, or transfiguration even, is a very African thing: You take something, and you transform it into another state, and then it becomes creatively admired.

SB: I like this idea of alchemy being something that’s deeply rooted in a culture.

DA: Alchemy is profoundly about the moment when human beings confirm a kind of engagement with nature that then becomes art.

SB: Let’s finish on the climate crisis. How are you thinking about it through an architectural lens?

DA: The precipice we now face is so present and clear. When I was a young architect, it felt further away. It felt like it was still “out there.” But the precipice is so very near. The trauma of this precipice is that it requires a joined-up ability to put on the brakes.

At once, I’m completely distraught at the juggernaut that’s been created by architecture, and our inability to find a way to transform it, but at the same time understanding that there is incredible technological innovation. Nanotechnology, which allows us to understand how to sequester carbon materials, would not even have been a conversation thirty years ago. We’re now talking about that for perhaps the most destructive material: concrete. That science is maybe about ten years away, so we’re right on the edge of cliff-jumping, or not.

There’s also a conversation about balance: mass-made versus mass nature. We know that both of those are at a tipping point. It’s now established that there’s almost more mass, give or take a decade, made in the world as there is mass on the planet. These two are really disturbing moments, because deeply rooted in my thinking about the ecology of making is to strike a balance and be with nature.

SB: How is this thinking playing out in your work today?

DA: I’ve become really obsessed with mud and rammed earth, and things that can decompose back. I started posting [on Twitter and Instagram] things like termite mounds. It wasn’t just because the form looks like towers. It’s this idea of a mass made from exactly the thing that’s on the ground, constructed into a form that creates the habitation. Then, when the community goes, when the queen mother dies, it just dissolves back into the earth. There’s something so deeply, profoundly powerful and edifying about it. That’s a lesson architecture needs to grapple with.

There’s one view, which is, Oh no, we’re worried about the scarcity of materials, and then there’s another view, which is: We need to move away from this idea of what I call the “prejudice of materials.” I’m interested in: Can you use mud to make a high-rise?

SB: Too few architects seem to be thinking along these lines.

DA: It’s maddening. This is the most pressing thing: how to make an architecture that simply goes back to the earth.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity from two conversations, recorded on June 9, 2020, and July 29, 2020, during the research phase of Alchemy: The Material World of David Adjaye (Phaidon), out this week.