Meet Seven Immigrant Women Who Shaped the Way America Eats

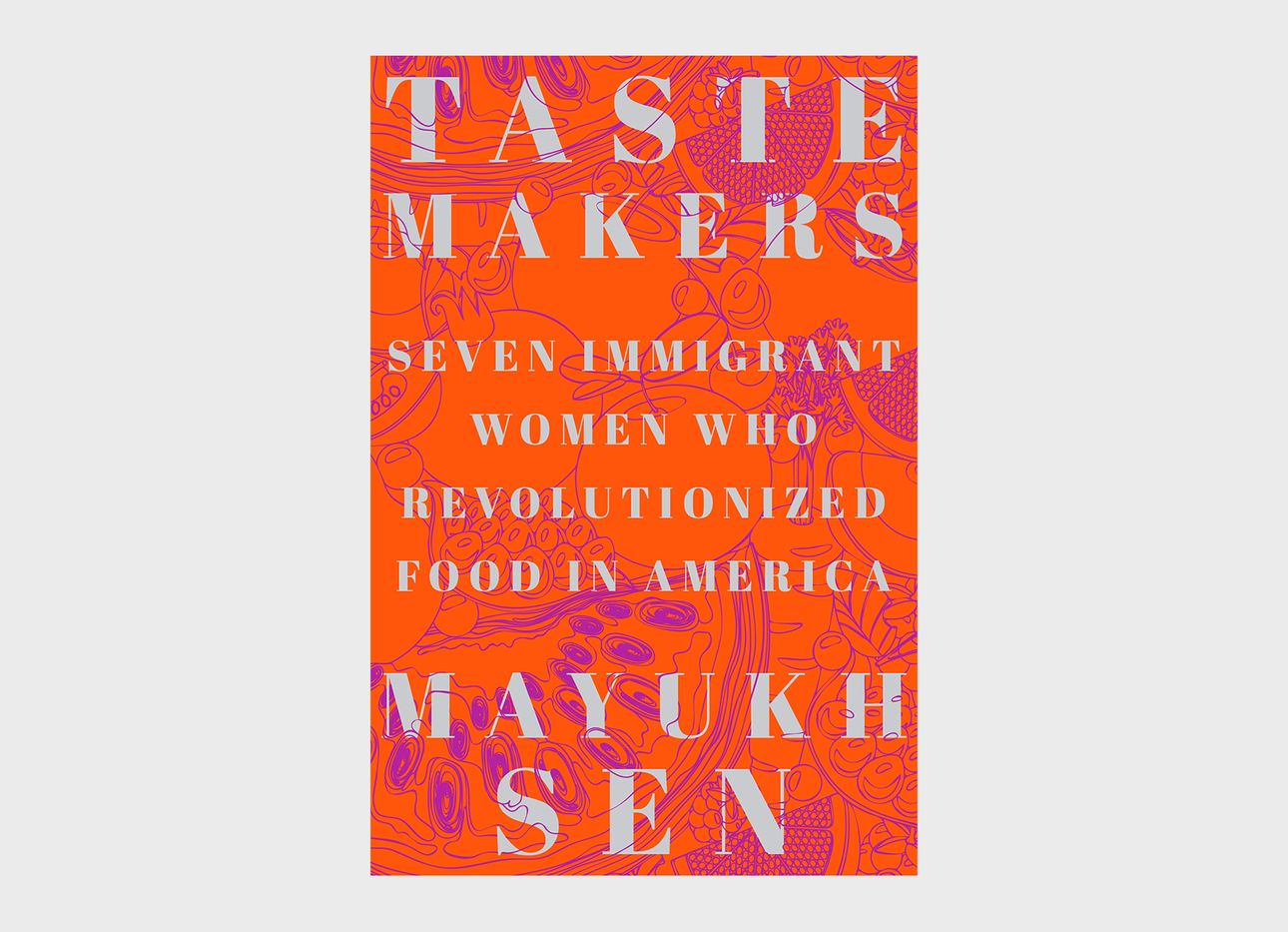

How can one shape America’s proverbial melting pot? Mayukh Sen, a James Beard Award–winning food journalist and professor at New York University, offers an answer with the stories of seven immigrant women, from World War II to the present day, whose culinary prowess shaped how and what people in the States eat today. Sen illuminates these pivotal chefs and food writers in his debut book, Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionized Food in America (W.W. Norton), out next week.

Each chapter is a biography of a culinary footprint. Sen profiles Najmieh Batmanglij, an Iranian refugee whose cookbooks reclaimed the identity that the Iranian Revolution sought to stifle; Norma Shirley, a Jamaican chef and restaurateur who started out by selling picnic baskets of Western European dishes with Jamaican flair to her community in the Berkshires; and Elena Zelayeta, a Mexican-born chef who, after going blind in the 1950s, became the first Latina woman to have a cooking show on television. He also surveys the lives of Chinese-American physician and cookbook writer Chao Yang Buwei, French chef and cooking teacher Madeleine Kamman, Italian-born food writer Marcella Hazan, and Indian chef and restaurateur Julie Sahni. At one point, Sen offers an interlude about Julia Child as a point of contrast, questioning the American public’s response to women based on cultural marketability.

Sen’s writing encourages intimacy between the subject and reader. By referring to each woman by her first name and refraining from directly quoting sources, he evades a sense of objective journalistic distance. That’s not to say his work isn’t well-researched. The vivid color and depth within his accounts of these cultural, historical, and personal trajectories stemmed from his subjects’ cookbooks, memoirs, and close friends and family; Sen interviewed Sahni and Batmanglij, the book’s two living subjects.

The stories also illustrate a range of perennial issues, such as the symbiosis between the food establishment and food media, and the social complexities of making a name for oneself as an “outsider” (and a woman) in the United States. Nodding to his queerness and Bengali heritage in the foreword, Sen even anticipates—and thoughtfully answers—a natural query: “Why is a man writing this?” By the book’s end, some of the people who stoked America’s appetite for diverse fare come into focus, likely leaving readers wondering why they haven’t heard of these women before. That’s largely the point of the project, Sen writes: “to question which immigrant stories our American culture values versus those it tosses aside—and why.”