The Piercing Prose of the Late Janet Malcolm

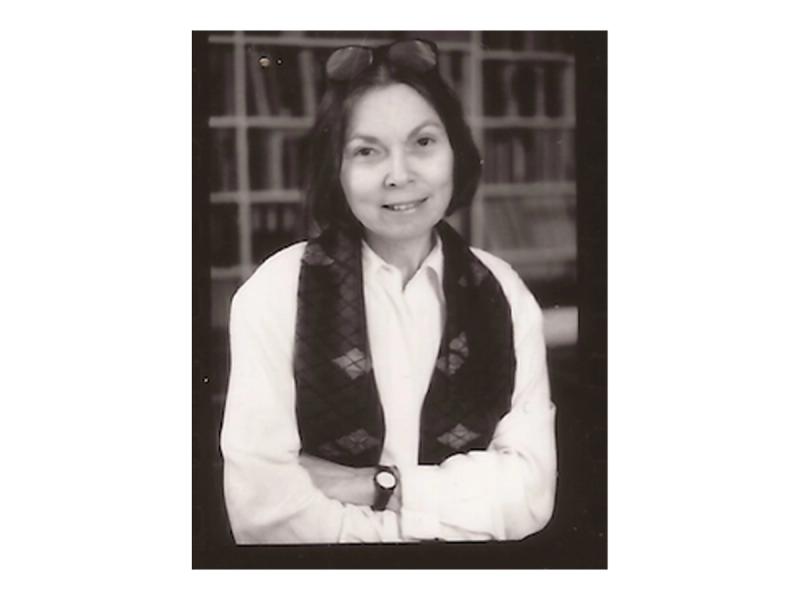

When Janet Malcolm first wrote for The New Yorker in 1963, her debut wasn’t in the form of the piercing prose she became known for, but instead a slim poem titled “Thoughts on Living in a Shaker House.” On the surface, it may seem an odd starting point for Malcolm, who would become one of the foremost writers about—and shrewdest observers of—psychoanalysis, the law, and journalism, and who would remain a New Yorker staff writer until her death, on June 16, 2021, at age 86. But the poem’s lines are indeed pure Malcolm: plainspoken, cutting in their clarity, and—save the use of the words “lineaments” and “epicene”—generally unpretentious. Consider the poem’s second stanza: “This house is full of pegs and sense,/A kind of grudging elegance/Informs each piece and artifact/Come down to use preserved intact.”

Shaker design was, in actuality, a fitting subject for Malcolm, and not just because some of her earliest pieces for the magazine were on interiors. As with Shaker constructions, Malcolm’s acerbic, sharply tuned writing was purposeful and perfectly executed. There was indeed a “grudging elegance” to it.

Many of Malcolm’s other early features were on photography (she was the magazine’s photography critic in the 1970s), a subject that was the heart of her first book, Diana & Nikon, originally published in 1980, and that is now—to come full circle—the focus of a newly published posthumous memoir, the wonderful, slender Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), her final hurrah.

To read Still Pictures is to meander through the house of Malcolm’s memory, each essay a framed photograph hanging on the walls of her mind. Malcolm herself once wrote, “The house of American photography has many mansions.” This potent and powerful little book is representative of hers. Its lines, rigorous and taut as Shaker chairs, merge to form an exquisite whole. The essays meander through a hard-to-parse past shaped by her father’s upbringing in a poor family (“the vestiges of his peasant childhood,” in her words), her family’s early years as Jewish refugees of the Holocaust, and the resultant “dread that permeated” throughout her life. (Malcolm arrived in the United States from Prague in 1939, when she was nearly 5 years old.)

Not so much an autobiography, Still Pictures is instead a meditation on memory—on, as Malcolm describes it at two turns, “memory’s willful atavism” and “memory’s perversity.” One sentence in particular from the book captures her perspective: “Autobiography is a misnamed genre; memory speaks only some of its lines.” Offering an alternative, less didactic definition of “memoir,” this book connects, via pictures, the shards of a life that was haunted by the specters of the Holocaust, and yet was also full of, as Malcolm herself would have put it, “horsing around.” (Writes Malcolm: “Our family was proud of the way we horsed around and had fun.”)

Throughout, gems of wisdom—the kind that can really only be accrued across a lifetime of deep contemplation and close observation—are to be found. Consider this Malcolm musing: “We are each of us an endangered species. When we die, our species disappears with us. Nobody like us will ever exist again. The lives of great artists and thinkers and statesmen are like the lives of the great extinct species, the tyrannosaurs and stegosaurs, while the lives of the obscure can be likened to extinct species of beetles.” Or this one: “Most of what happens to us goes unremembered. The events of our lives are like photographic negatives. The few that make it into the developing solution and come photographs are what we call memories.” Or this: “All happy families are alike in the pain their members helplessly inflict upon one another, as if under orders from a perverse higher authority.” Only once in the entire book did a line fall flat for me, and it was this one, which seemed to be a bland generalization, uncharacteristic of her work: “In literature interesting things happen to interesting people; in life, more often than not, interesting things happen to uninteresting people.”

Except for three of the essays, each features a photograph or two (or three), which serve as psychic jumping-off points for Malcolm to enter some of her trickier-to-reach inner realms. While Malcolm was famous for her “unflinching gaze,” as a New York Times obituary described it, she found it particularly tricky to turn that gaze on herself. “I would rather flunk a writing test than expose the pathetic secrets of my heart,” she writes in “The Apartment,” one of the book’s final essays. “The prerogative of cowardly withholding is precious to the most apparently self-revealing of writers. I apologetically exercise it here.”

While this point is true—within bounds—through the medium of photography Malcolm is able to access and explore various lost-in-time chasms of her life with acuity, slippery realms that otherwise would have likely proved fruitless or frustratingly difficult to grasp without this series of flimsy images: her early time in America as a Holocaust refugee (“a painful and shameful reality of my inner life as a child”), the mythologies of her parents, her mother’s influence on her becoming a journalist, her evolving sexuality (“the enduring injuries of our hapless earliest erotic encounters”), her experiences with psychoanalysis (“the humility of Freudian dream interpretation”), and her late husband’s subtle, wink-wink humor (“a wonderful exercise in absurdism”).

That the photographs Malcolm writes about are themselves seemingly quite ordinary and rather mundane, the kind found in many a family archive, makes this series of essays all the more extraordinary. In one picture, a young Malcolm poses with her sister, along with “three people I don’t recognize,” in front of a car. Another is of her P.S. 96 class, taken during a visit to the Empire State Building. Another, a sepia postcard inscribed to her father, features a portrait of the Czech film actor, director, and writer Hugo Haas. Each of these leads Malcolm down rabbit holes that sharpen the focus of her precariously remembered past.

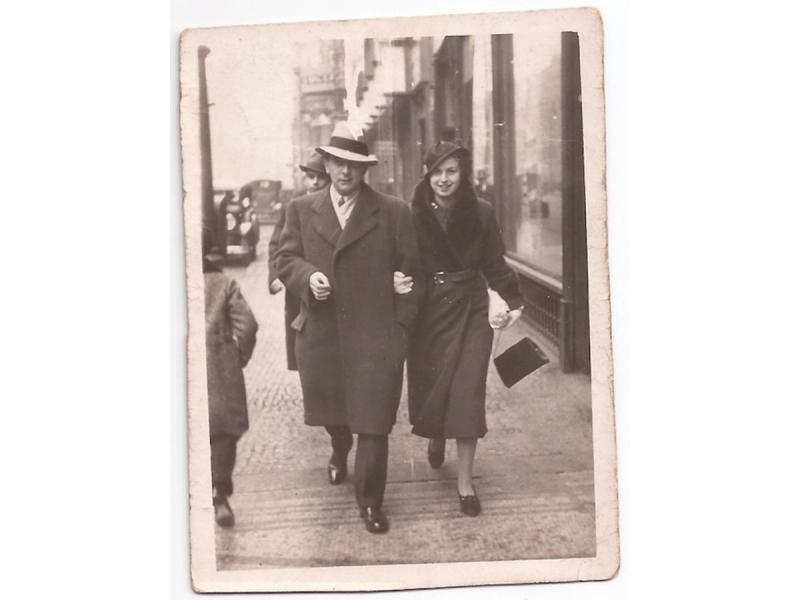

In one family photo, dated June 12, 1949, she stands in a row with her parents and sister on a boardwalk in Atlantic City, New Jersey, her father a kind of caricature in his broad-shouldered, oversized suit. “He looks like a vacuum-cleaner salesman,” Malcolm writes matter of factly (and wryly). Contrasting this scene with a photo of her parents strolling in Prague in the 1920s or ’30s, looking trim, dapper, and elegantly appointed, and another, of her father “wearing eyeliner and lipstick and a wig and a woman’s dress, posed with another man in drag and a third man in a tuxedo and bizarrely oversized round glasses,” Malcolm comes to realize how the Atlantic City photograph showcases her emigré parents’ “embrace of the new life of less money and tamer pleasures”—a new world, she writes, that they “gamely negotiated.”

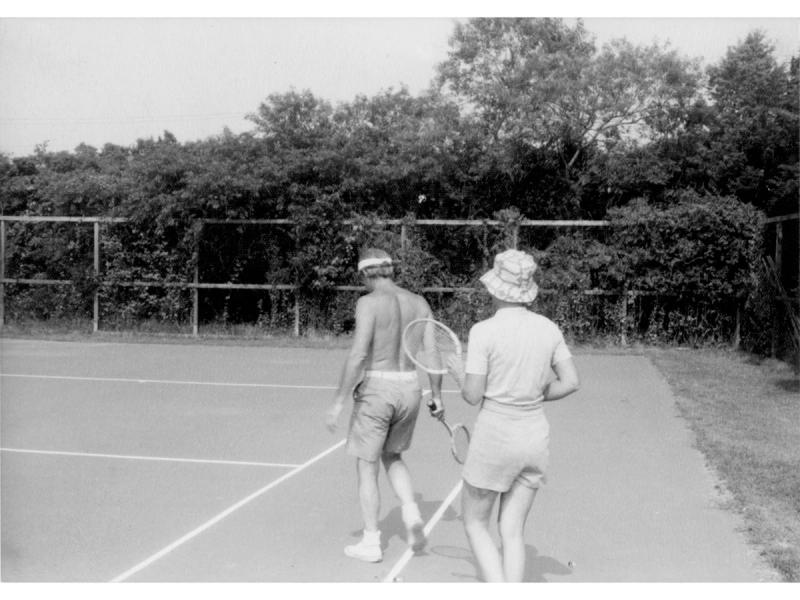

Perhaps my favorite picture is the one in the book’s final essay: a snapshot by Malcolm’s late husband, the longtime New Yorker editor Gardner Botsford. Depicting, as Malcolm writes, “a man and woman wearing shorts, walking one behind the other on a tennis court,” the image is unremarkable, utterly bland, and not even necessarily well-framed or -composed. Writes Malcolm: “There was no reason for the existence of this picture.” Still, there is a sort of avant-garde quality to it, in line with the images of Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Joel Meyerowitz, and others whose works appear in the 1974 Aperture book The Snapshot. Malcolm writes about how, mischievously toying with this aesthetic connection, she managed to insert Botsford’s picture into a New Yorker spread she wrote about The Snapshot. “The temptation was too great,” she writes. One assumes there would have been a critical letter to the editor about this lark, yet upon publication, not a single person seemed to notice. The result, for Malcolm, was what she calls “wicked joy,” a phrase that sums up the exact feeling I had after reading this enjoyably spare and poignant collection.