Spike Lee’s Prolific Career Gets the Spotlight, Naturally, in Brooklyn

Until February 4, 2024, the Brooklyn Museum will have an (unofficial) new name: the Crooklyn Museum. As of last weekend, the fifth floor is hosting “Spike Lee: Creative Sources,” an immersive exhibition featuring more than 450 objects—ranging from artwork, sports jerseys, and film posters to photographs and musical instruments—from the award-winning filmmaker’s personal collection.

Organized by Kimberli Gant, the museum’s curator of modern and contemporary art, along with curatorial assistant Indira A. Abiskaroon, the exhibition celebrates Lee’s long association and connection with Brooklyn through various points of inspiration. Within seven thematic sections—“Black History and Culture,” “Family,” “Brooklyn,” “Photography,” “Cinema History,” “Music,” and “Sports”—museum visitors are taken on a dynamic journey through Lee’s creative process.

“Spike has been in Brooklyn almost all his life,” Gant says. “So many of his films take place here; he coined the term ‘Da People’s Republic of Brooklyn.’ If the Brooklyn Museum is supposed to represent the art and culture of this borough and present it to the world, how could we not present such an important storyteller to audiences?”

When asked about the genesis of the show, Gant says that the exhibition demonstrates how you get from A to Z, not in the sense of ‘this is the process of making a film,’ but ‘this is the process of how Lee gets inspired and fueled.’”

Selected clips of Lee’s 24 films, made over a span of 37 years, are woven throughout. “We didn’t want to do a traditional film exhibition,” Gant says. Instead, the selected clips serve to echo the thematic sections. “I watched a lot of Spike Lee films over the past year and a half, trying to find incredible moments in different films and documentaries that would augment the objects.”

Lee refers to the blend of ingredients that he puts into his films as “a Spike Lee joint,” and “Creative Sources” can be viewed as a physical and visual representation of those ingredients. The journey begins in “Black History and Culture” with a clip from one of his most famous films, Malcolm X (1991). Posters of Angela Davis share space with a framed African National Congress flag signed by Nelson and Winnie Mandela, along with a “Colored Waiting Room” sign. These objects speak to the rich, complex nature of Black history, which Lee also reflects in films like Bamboozled (2000), a dark comedy about a modern-day minstrel show.

Gant knew from the start that she wanted to include a “Family” section in the show, noting that “so many of the familiar relationships in his films are complex but loving and joyful.” Here, artwork by Lee’s children is displayed next to looped scenes from Crooklyn (1994) and Mo Betta Blues (1990), while a tribute portrait of Lee’s father, Bill Lee, a jazz musician who wrote the scores for many of his son’s films, watches over the gallery. “Family” segues into “Brooklyn,” which showcases the role the borough plays in films She’s Gotta Have It (1986) and Do the Right Thing (1989).

The “Photography” section is almost a “mini U.S. photo history retrospective,” says Gant, with works by James Van Der Zee, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, and Gordon Parks. The wall text for the section notes that photography makes up one of the largest parts of Lee’s collection. Lee’s influences and achievements are also on display in the “Cinema History'' gallery, including his handwritten speech for winning the 2019 Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for BlacKkKlansman (2018). A guitar owned by Prince and records from Stevie Wonder appear in the “Music” section, which pays tribute to the most important artists and scores featured in Lee’s films.

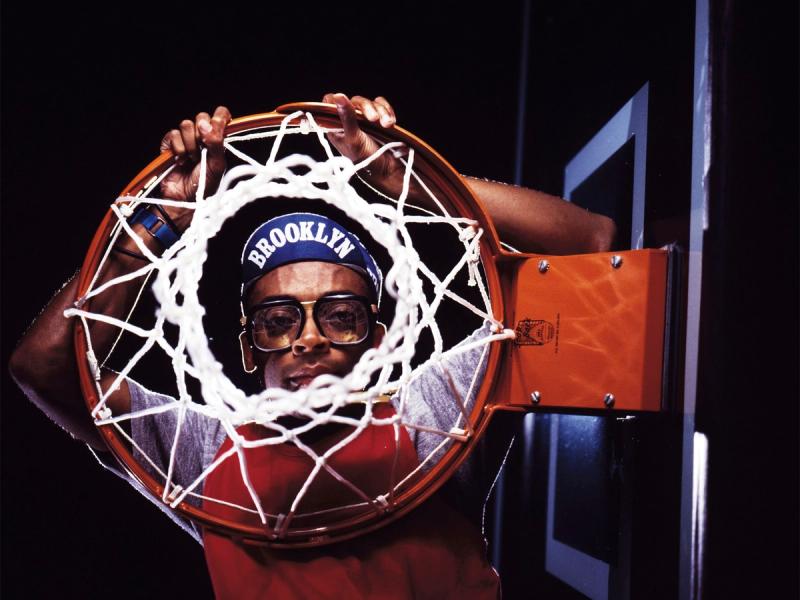

As the director is known for being a lifelong New York Knicks fan, the exhibition wouldn’t be complete without a display of jerseys, tickets, and newspapers depicting his courtside behavior. Pendants from the Brooklyn Dodgers, a photograph of the New York Black Yankees, and signed memorabilia from sports world luminaries help to round out the “Sports” section.

The exhibition finishes with three film clips featuring dancing scenes pulled from Lee’s films, an ode to the fact that, even though his films often tackle heavy subject matter, he always makes room for celebration and allows his characters to find moments of joy. It feels fitting, then, that “Spike Lee: Creative Sources” is itself a celebration of the borough, its stories, and the storyteller who brings them both to life.