Spencer Bailey on Memorials, Abstraction, and the Act of Unforgetting

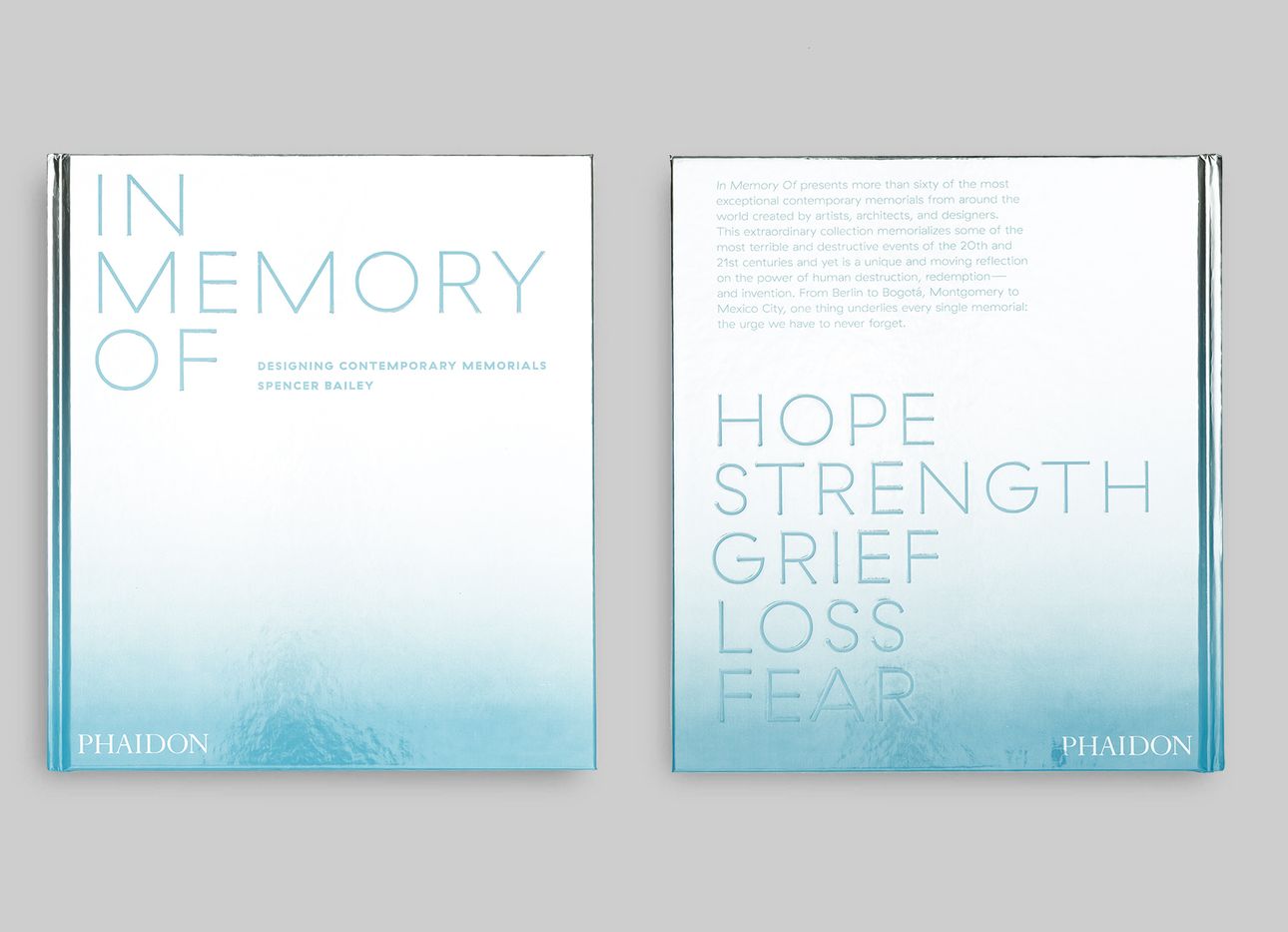

At age 3, Spencer Bailey, writer and editor (and co-founder of The Slowdown), survived the crash-landing of United Airlines Flight 232 in Sioux City, Iowa, on July 19, 1989. In the wake of the tragedy, he found himself the subject of a memorial sculpture, called “The Spirit of Siouxland,” based on a famous photo of him being carried to safety in the arms of Lt. Col. Dennis Nielsen. That cast-in-bronze depiction serves as a jumping-off point for Bailey’s forthcoming book, In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials (Phaidon), examining the power and potential of memorials designed over the past 40 years, from Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial (1982) in Washington, D.C., to Peter Eisenman’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews (2005) in Berlin, to MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial (2019). Here, he describes the process of working on the book, and tells us why the power of abstraction may help us all to heal.

You began working on this project nearly thirty years after the Flight 232 crash. What has it been like to process and revisit that trauma and experience through this more expansive outlook?

The book was, for me, a way to unpack this deeply personal experience in a global, collective way, and to understand what it means to be memorialized in a greater context. Whether it’s war, genocide, terrorism, or natural disaster—all of these sites respond to events that took place, each in their own way, and contributed to my understanding and questioning of: Was the way that I was memorialized [in a figurative statue] actually effective? What does it mean to be representative of something much larger than yourself? Ultimately, the conclusion I came to was that there is, in fact, a solution to memorializing in the modern age, and that’s through abstraction. Abstraction reflects the society around it, because it doesn’t dictate a meaning or message the way that a figurative statue does.

One of the compelling aspects of this book is that you present a critical edge to your observation of memorials. They carry a sense of permanence, but are also entirely subjective, and are sometimes fraught with conflicting interests and intentions.

I’ve come to understand the failure of figurative memorialization—or, more accurately, monumentalization—from the Flight 232 Memorial. I came to represent this symbol. There’s something wrong about that: the motif of a child being carried doesn’t bring a lot of clarity. It doesn’t show the myriad experiences and multiple perspectives on what took place that day. To me, that statue is just projective of a hero’s story, not reflective of the tragic event it’s intended to commemorate. I don’t see myself in it.

Especially striking is what’s not shown at the site. Why is there no mention of the pilot, Alfred Haynes, who guided the plane to the ground? Why are there no names of other crew members or passengers? At the very least, what about the dead? A different design, I think, one inscribed with the names of those lost, and with a more sculptural or abstract quality, would have better captured the detritus and tragedy of that event. There’s a real way forward, if we want to understand, collectively, the power of memorialization, and that’s to literally stop putting ourselves—our human figures—on pedestals.

Abstraction leaves the viewer to reflect, rather than take away a set narrative.

Abstraction is all about metaphor. It allows for complexity and contradiction. An abstract memorial gives each visitor the opportunity to read and respond to it in their own way. That’s so different from what happens when you’re looking at a figurative statue. We live in such a chaotic world, where there is no black and white, where there’s such diversity of people and perspectives, and we need to make memorials that reflect that multitude of experience. Abstraction, with specific intent, is a way to do that.

Hua Hsu recently wrote a beautiful piece in The New Yorker that got me thinking a lot about this very thing—about “commemorative justice.” Instead of a monument, he asks, why not a portal? I love that idea. That’s basically what the memorials in my book are: portals. This notion of the portal, inviting something deeper, taking you to a place, offering you an opportunity to slow down and turn inward. A portal into yourself—there’s something really profound in that.

As someone who has interviewed and written about art and architecture for years, what have you learned about this genre—if we can call it that—of the built environment?

In Memory Of is a global survey of art, architecture, and landscape, but I would say it’s also about the human experience and emotional weight. The book is framed in our contemporary world, but memorialization goes back centuries, from burial mounds to pyramids. There are a lot of notions—arguably there have been since the beginning of mankind—around what a memorial is. But in speaking to many of these architects and artists behind these memorials, the thing that hit me was the human experience behind all of it. These projects are so rooted in story, and often trauma, but underlying all of them is an incredible testament to human strength, and the ability to move forward and progress—without forgetting what has happened.

You couldn’t have anticipated this book would come out at this moment in history, where grieving and loss have multiplied, amid the pandemic, protests, and a political maelstrom. How have the events of 2020 changed the way you’re thinking about memorials?

It was really strange to turn in my final copy of the book in the first week of March, right before we went into lockdown. I’d spent more than a year and a half researching, reporting, and writing this, thinking about mass atrocity and mass deaths, so to be confronted with it so head-on just a few weeks later, was a peculiar feeling. I don’t think it provided any new insight for unpacking the pandemic, necessarily, other than thinking about the fact that it’s important we recognize, at least on some level, that there are barely any memorials to the 1918 Spanish flu. That may explain, at least in part, the cultural, political, and social amnesia that has led to our catastrophic present.

Memorials are something we need—not only to remember, but more importantly, to humble us and allow us to feel loss, grief, fear, hope, and strength in our bodies. Not to just think about those things, but to feel them. I look at memorials as poems of the built environment. They are expressive, visceral, concrete reminders that ultimately help us heal.