A Commemoration of AACM’s Legacy in Experimental Jazz

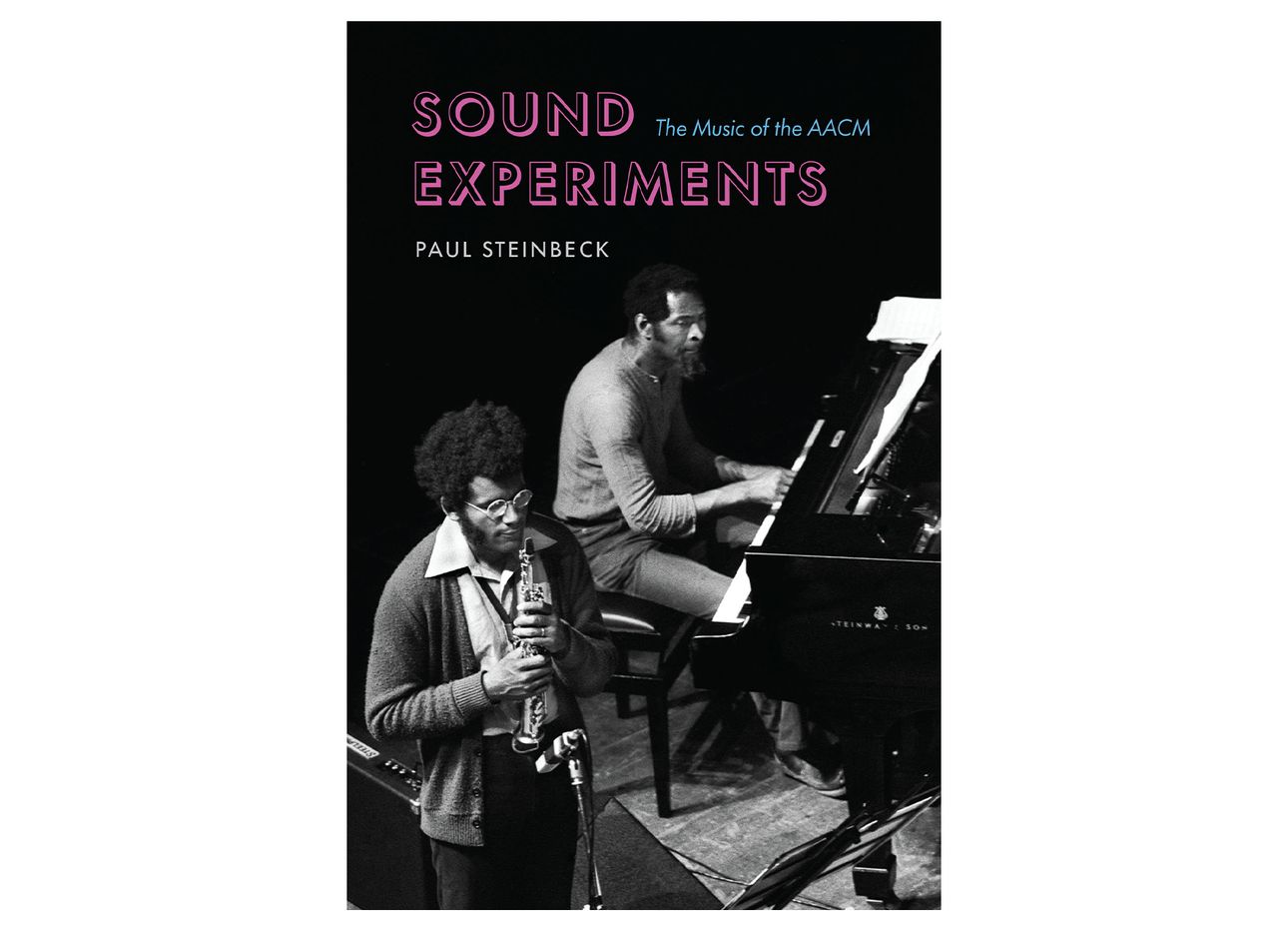

Call it “free jazz,” “avant-garde,” or “the new thing.” Just don’t call it predictable. Founded in Chicago in 1965 and still thriving today, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) has long been an emblem of experimental, improvised jazz. As author Paul Steinbeck describes in his new book, Sound Experiments: The Music of the AACM (University of Chicago Press), this collective came together to play and promote fearlessly original, spontaneous music. “AACM members combined composition and improvisation in unprecedented ways,” Steinbeck writes, “creating modes of music-making that bridged the gap between experimental concert music and contemporary jazz.”

In the mid-20th century, leading Black jazz musicians had been excluded from the white experimental-classical community. From the beginning a registered nonprofit, AACM countered this trend by primarily bringing on musicians of color, and helped to establish its members’ careers, holding concerts and pressing their albums. Given a chance, the AACM’s members—from founder Muhal Richard Abrams and the legendary Art Ensemble of Chicago (perhaps the Association’s most celebrated act), to saxophonists Anthony Braxton and Roscoe Mitchell, to still-active trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith—blasted through musical guardrails, broadening the free-jazz sound that had begun with Ornette Coleman in the late fifties. AACM-produced records often teemed with diverse instrumentation (finger cymbals, ox-jaws, pennywhistles), yet its solo concert albums are often the most powerful, rising to the intensity of religious ritual.

Rather than a tour through AACM history, Sound Experiments serves as a deep dive into six of the organization’s seminal albums across the decades, which makes listening to the music while reading a whole new kind of experience. (Most of its releases are available on streaming platforms.) Be it Abrams’s ambitious Levels and Degrees of Light from 1968 or Mitchell’s 1977 solo-concert album Nonaah, the latter which finds the saxophone improvising to his audience’s jeers (they’d come to see Braxton) and eventual cheers, Steinbeck makes an authoritative guide. In fact, the book is detailed enough that its jargon can sometimes come off as wonky to a nonmusician. But just like when listening to the AACM’s pioneering music, it’s best to let go of expectations and allow it to wash over you.