A New Book Traces the Evolution of Modernism in the Rocky Mountains

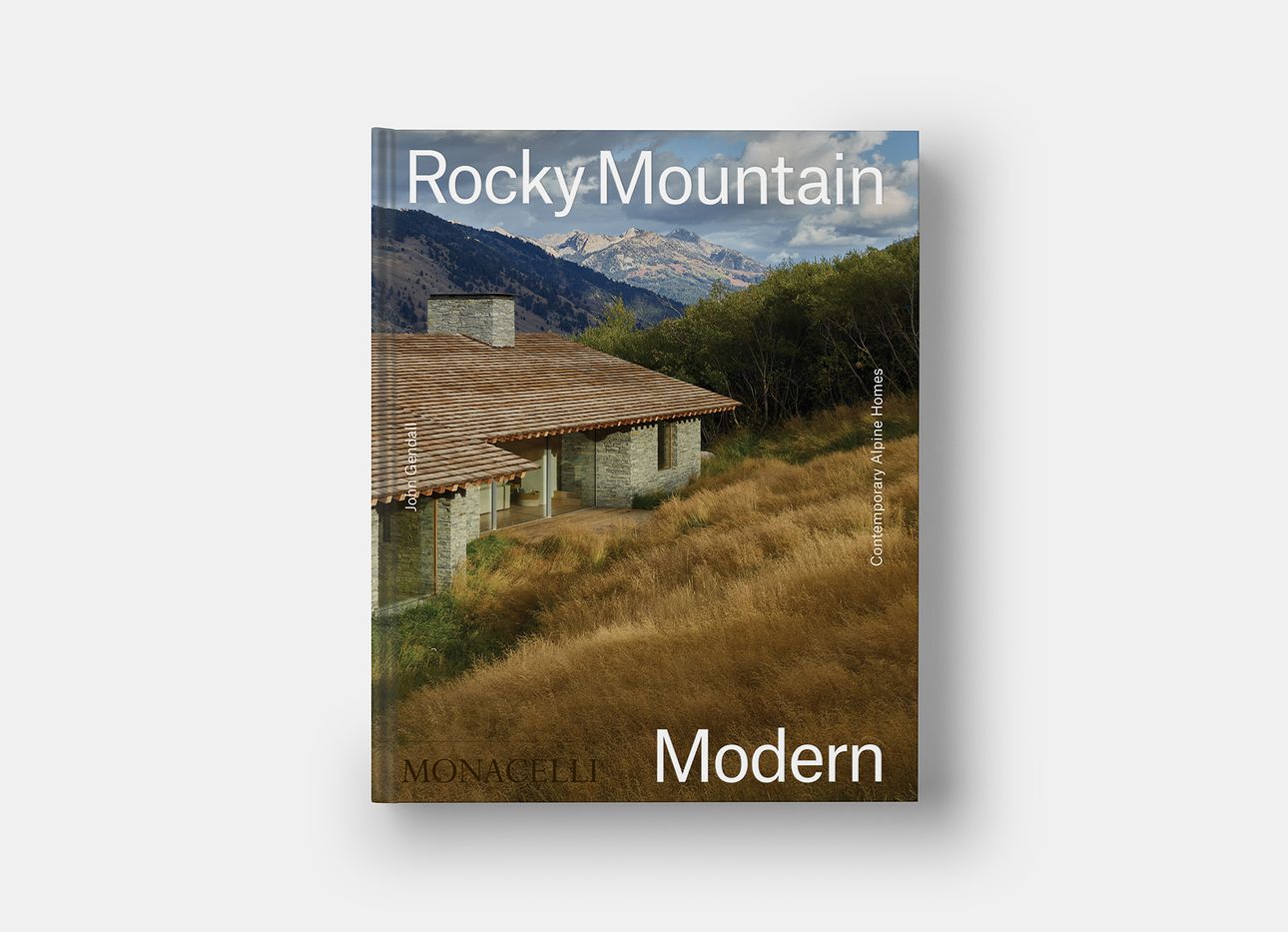

The jagged spine of the Rocky Mountains is too beautiful to mar. Yet over the years, developers and builders have managed to do just that: The planet’s third-longest mountain range is covered in lackluster homes. But beyond the fray, courtesy of some extraordinary architects, there’s a group of standout residences that both honor the surrounding splendor and represent the latest evolution of a regional style that began in the mid-20th century, when leading architects including Marcel Breuer, Buckminster Fuller, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Eliot Noyes, and Eero Saarinen completed commissions in the Western United States, transforming it into a hub for architectural modernism. Journalist John Gendall, who grew up near the Canadian Rockies, surveys 18 of these distinctive structures in his new book, Rocky Mountain Modern: Contemporary Alpine Homes (Monacelli Press).

Following an introduction that traces the region’s often-overlooked history of modernism, Gendall devotes an entire chapter to each contemporary project, primarily using photographs (there are more than 200 of them throughout) to tell its story and to celebrate its extraordinary setting. “I tend to go far afield to write about projects, passport and plane tickets in hand,” says Gendall, who has written widely about architecture and who currently serves as a visiting scholar at New York University and a visiting professor at Pratt Institute. “This book was the opposite: a return home. I wanted to bring attention to the many exceptionally talented architects designing homes in the Rockies that draw from a Modernist discourse—modern not only in aesthetics, but also in the ways they tackle some very challenging functional requirements.”

The book’s homes elegantly and inventively confront and adapt to an array of conditions, including strong winds, intense sunlight, heaps of snow, and varied, complex landscapes. Among those featured are Idaho’s Sun Valley Residence—the first house Allied Works’s founder, Brad Cloepfil, ever designed—which celebrates its surrounding sagebrush, aspen trees, and the Sawtooth Range with a series of U-shaped walls and floor-to-ceiling windows that frame views. Courtyards provide privacy while minimizing the sun’s intensity; the structure’s concrete walls protect against fluctuating temperatures. In Montana, between Whitefish Lake and a ponderosa pine forest, a home designed by Olson Kundig has double-height window walls that create the feeling of being on the forest floor. Upstairs bedrooms, positioned at the same height as the tree canopy, evoke a sensation of looking out from a treehouse. A residence set on a working wagyu cattle ranch in Golden, New Mexico, designed by architect Rick Joy, serves as a live/work retreat that accommodates its transitional terrain, where the Sangre de Cristo Mountains meet sprawling desert plains. A multi-hip roof captures and stores rainfall and snow melt, and shou sugi ban, or charred cedar, siding covers the entire structure as a safeguard against the area’s wildfires.

Elsewhere, projects in Aspen, Colorado; Jackson Hole, Wyoming; and Utah’s Powder Mountain surprise and delight with their skillful use of local materials and timeless forms. While the homes featured represent an array of typologies, they’re united in their bold efforts to incorporate and embrace a distinct and diverse terrain, living up to the true meaning of “site-specific.”