Paola Navone on the Radical Act of Giving Things Away

Radical by nature and a rule-breaker at heart, Paola Navone has been on an endless self-described “treasure hunt” for the past 50 years. Immediately after graduating from the Polytechnic University of Turin, in 1973, she traveled to Africa, where she spent months roaming the continent and taking in its vast beauty and Indigenous architecture. The following year, she published her university thesis as a book, Architettura Radicale, and then went on to join the Italian radical design groups Alchimia and Memphis. From the early 1980s to 2000, she lived between Milan and Hong Kong, seamlessly shuffling between the worlds of European industrial manufacturing and savoir faire and Asian craft and street culture—a path she has continued on to this day. Throughout, she has always been one to push boundaries and search for alternative approaches to design.

In addition to designing products for companies such as Alessi, Baxter, Bisazza, Cappellini, Driade, Exteta, Gervasoni, and Poliform, Navone has also long been an inveterate collector of objects, many of which find their ways into her interiors projects, such as the 25Hours Hotel in Florence and the COMO Point Yamu hotel in Phuket, Thailand. Across her life and rich body of work, she has amassed an incredible collection of pieces that have caught her roving eye, from 1950s Sainte-Radegonde ceramics from France to antique metal spoons from India.

During this year’s Milan Design Week, Navone will present “Take It or Leave It,” an exhibition organized in collaboration with The Slowdown, curated by Daniel Rozensztroch and featuring an eclectic assortment of hundreds of items she has collected or designed over the years. The result of decades spent experiencing and seeing the world, the show will serve as yet another radical act for Navone—one in which she’s giving these objects away, for free, through a lottery. (For more information or—if you’ll be in Milan—to sign up for the lottery, see our exhibition page.)

More than just a provocative exercise, “Take It or Leave It” is an effort in upcycling and reuse, underpinned by a projective, climate-forward manifesto. The exhibition boldly considers: Rather than relying on virgin materials and energy-intensive processes, why not appreciate and honor the things we already have, and give them a new life?

During a recent visit to her wondrously arranged home in Milan’s Zona Tortona neighborhood, I spoke with Navone, who’s a longtime friend of mine and the subject of my 2016 book, Tham ma da: The Adventurous Interiors of Paola Navone. We discuss our collaboration on the upcoming “Take It or Leave It” undertaking, the notion of attaching “high” and “low” values to objects, and why Navone doesn’t consider herself a “collector.”

Let’s start with the most important question first: Why do you want to do this project?

[Laughs] I have no answer to this. Or I suppose I have many answers. The first reason is because you liked the idea, and you decided that we were going to do it. Otherwise I never would have started this nightmare project. That’s the real, honest answer.

At this point in life, my attitude is to go around the world—I say “the world,” but it could be the supermarket down the street or India tomorrow morning—and detect something interesting from a mountain of merchandise, or from a big pile of garbage, or from the waste of a certain industry. I still love to do these things. It’s my life. It’s my way of seeing the world.

I believe that design—the act of design—is to give shape to an idea. But it’s also an act of design, in my opinion, to detect something that you find interesting for some reason and take it out. Sometimes you find that when you take that thing out, it’s a design product in itself. To give the status of a “design object”—or a “design material,” for architecture—to something that comes from waste or garbage, I think is very important.

More and more, I give the same status to furniture and accessories that come from the design industry north of Milano, in Brianza—very nice, with a number in a catalog, a price, a delivery time, and so on—to two chairs I found in Normandy, because I exchanged two old chairs with two new ones. That’s another story: You can trade.

Yeah, it’s this idea of placing factory-made, high-quality production, Italian whatever alongside something you found on the street in, say, Hong Kong.

Yes. This comes out of the idea of “high” and “low”: What is high? What is low?

You have this incredible mix of objects here, like these [points to cement vessels made by a craftsman in northeastern Thailand]—where it’s a high art form, but it's applied to this “low” material.

It’s not even ceramic! Which is already considered a technique—you need a kiln. With this, you need nothing. You need your hand and your imagination. This guy uses water, cement waste, and iron waste.

So why do I want to do this? To be able to continue on this crazy activity [of acquiring and amassing a collection of objects], at a certain point you are somehow surrounded by thousands of elements, thousands of objects, thousands of colors, thousands of samples. Some of these old things, I feel, are at the end of their life. Sometimes, I take something home for a specific reason—or maybe not. Then the object is there, and it takes up space, and I need to bring in more life, more life, more life. So the idea of what I'm going to do [with all of this stuff] started to come to my mind.

Sometimes I wake up, and I’m very radical. I say, “I would like to get rid of everything that’s here, pretend it’s the year 2000 [when I moved into this home and studio], and start again from zero.” Then I start to say, “I need a chair to sit in, so let’s keep the chair. I need some plates to eat [off], so let’s keep the plates.” So after my radical nuclear bomb of an idea, I start negotiating with myself. [Laughs] Then I consider, Okay, maybe I’ll drop a missile, not a nuclear bomb. I go back and forth, asking, “What can I do?”

I have some friends in France with this magazine, and every year they organize a brocante, or flea market—like a yard sale in America. That’s such a heavy job. I don't think the money I would get for these objects would pay me for the trouble to organize this. It makes me miserable to think about. For example, this mushroom there [points to a metallic sculpture]—how much can I ask you to buy this? This mushroom, for me, at a certain stage of my work, had a lot of value. So which value do I ask? Do I ask you for one thousand U.S. dollars or ten euros? I’d rather give the mushroom to you, and bye-bye, you go away with your mushroom; come back for dinner. [Laughs]

So the “why” of getting rid of all of this stuff is that most of it has lived the life with you that you wanted it to live, and you're ready to let go of it.

Yes. I want to be free to bring in new things—new ideas. Like these [points the cement vessels from northeast Thailand]. I have to make space for these.

I think a lot of people would still go ahead and try to sell them. So when you told me about this crazy idea, I was thinking, That’s a radical act: to give something away. To say, “These are things of value, and they’ve brought value to me, but now I think they should bring value to other people.”

When I see things like these ceramic vessels in the northeast of Thailand, in the middle of the mud, I'm ready to pay whatever you ask me. It’s very rare that I negotiate. Then I bring them here, I absorb all the energy [from these objects] I need to, and then I want to sell them. What is the value? For me, they had a very high value before. Now it’s less, because I already want to get something else.

Also, the idea of saying, “Oh, this is thirty-five euros, the other is twenty-three, but the other is bigger—I really cannot. Of course, we have to make money—we all need to have enough money to be happy. But we cannot also drive ourselves on the concept of money. What is the point? I paid six dollars for it, so now, if I give it away, I have six dollars less in my pocket….

Could you elaborate on how you think about the value of an object? To me, that's a pretty interesting component of this exhibition.

One idea of value is simply the way your eyes look at something and decide—somehow select, in between many other things—a material, let’s say, which is distributed in certain channels, and maybe those channels of distribution are not the top of the market. They could even be at the bottom.

A good example of this is when I did the project for Como in Phuket. I told them, “I know this country very well. I know that we can have the most beautiful materials.” The whole hotel was done in terms of materials—tiles, flooring—with ordinary, locally made ceramics. This is a market where people never go to look for something “interesting.” But Thailand is historically a ceramics country, although the technical quality of what they sell is not so-called “perfect” from European industrial judgment.

I think that “low” can be “high” just because you look at something with a specific perspective and you know in your brain what you’re going to do with it. Because if you have this “low” material in your hand and you don’t do something with it, it’s difficult to turn its “low” value into something that’s “high.”

Right. These materials on their own would really be—

Junk! [Laughs] Sometimes, it’s also the attraction for the material, for the simple aesthetic point of view. For example, in the markets in Asia, they have all these kitchen utensils done by turning aluminum. This turning technique is very interesting. Finally, I bought this aluminum because I like the shape of this turning system—this turning savoir faire. It turns out that I like aluminum, so that’s why I’ve accumulated all these things in my kitchen. Some of them are everyday, little trays for coffee. But some of them teach us how to smash the aluminum, and then we transfer the idea into something else, which becomes a product in itself, in another word. So some of those “low” value items, they stay low value, but they give us information or ideas on how to do something else.

It's like a transference.

In this case, they’re like a reference. They don’t become “high,” like the other ones. They stay low, but they give us the idea on what to do in the production of something. They’re a kind of collection of design ideas.

You sort of alluded to this, but tell me about your approach to collecting. When did this practice start?

It started immediately. When I was in Africa [after graduating from university, in 1973], I was already collecting things, and of all those things I got back then, I got rid of everything, I only have one thing left—this blue beaded lady.

[Back in the early seventies] I already liked to buy hand-blown glass. I liked the magic of the transparency of the glass—the reflections. I had a lot of junk in my house in Torino, too.

Would you describe yourself as a collector?

No, I’m not a collector. I’m not like Daniel [Rozensztroch, the curator of “Take It or Leave It”], who has an integralist mind. He decided to collect—

Spoons!

Spoons. For three years, he only thought about spoons, bought spoons all over the world, put together hundreds of spoons. A fork wouldn’t work. If it’s not a spoon, it’s out. So he has this package of things which are always very consistent.

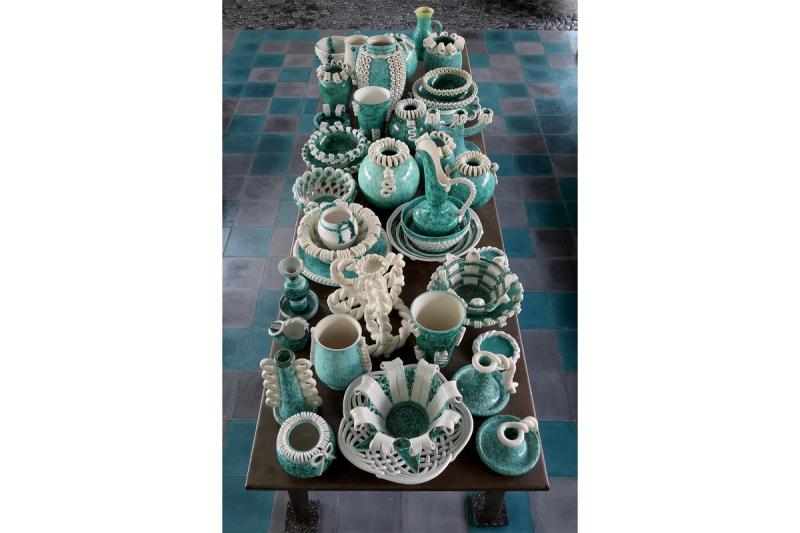

I have two “real” collections, this one [points to a table full of Sainte-Radegonde turquoise ceramics, from the south of France] and the Chinese Liao ceramics, in the dining room. I’ve always liked this funny technique, from the south of France, in the 1930s and ’40s. It was from the Printemps department store [in Paris]. These, I’ve always collected. Some of them I paid for, and they were very expensive, some of them I don’t—I don't even remember where they came from. Now, I really have a lot.

Then, the Chinese Liao [dynasty] ceramics pieces, I started to buy because Liao was one dynasty that was not considered “high” from the point of view of collectors of Chinese ceramics. They buy much more recent porcelain. These are one thousand, two thousand years old. They don’t really appeal to the Chinese collectors. So, after twenty years, I started to see some around, but they’re not really famous. I also have some Ming [dynasty] pieces.

The rest becomes a family, like these [points to the northeastern Thailand cement vessels]. I was there, in that garden, with that guy. I could have bought one hundred of them. But they were very expensive, and also very heavy, and I had to ship them here. So I bought only these. They become a family because they land here.

These aren’t like Daniel’s thousands of spoons, which then became a book. Suzy [Slesin, the publisher of Pointed Leaf Press] makes all these books for him. Me, I just collect seemingly random things. I have all these [interiors] projects, and they mostly have nothing to do with each other, one to the other. So my radar is like this [moves hands up and down], like a pixel radar. Zoom—I take this; zoom—I take that.

So many of your objects also tell stories, from the Thai figure there holding the offering bowl, to the large sugar ceramic urn, to that oversized ceramic fish, to those gold pigs. How do you think about the storytelling aspect of this project?

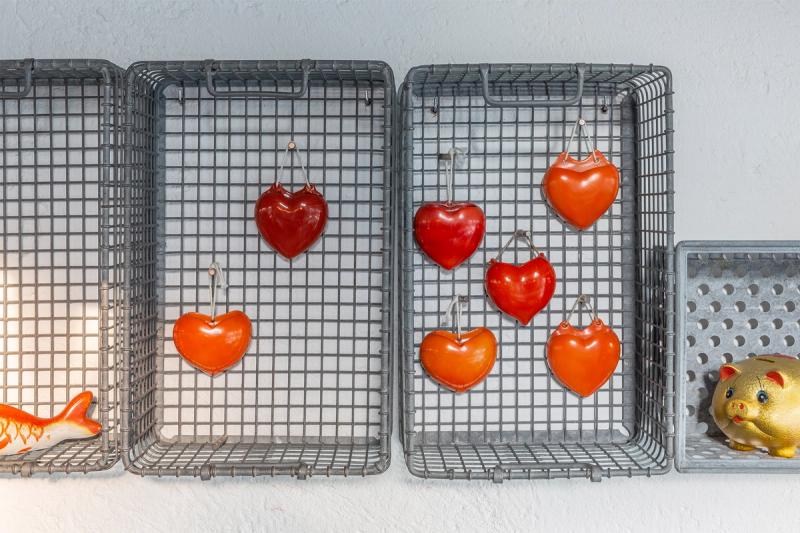

Some objects have a big story. Like these: I was in Thailand, I met this guy, I went to his house in the middle of nowhere.… Or that seahorse there: I found it on the island of Santorini, in the middle of a market of Chinese-made things. And those little hearts are Austrian. They’re vases—you put a little plant inside each. Those gold pigs are Chinese. I bought them in Singapore on the street.

What makes you decide to get something?

The fact that I detect something. That’s it. It’s a very sharp and fast act. To decide what to take is a fraction of a second, when my eyes stop on something.

It’s like you’re swimming. I remember you mentioned that you’re a Pisces and described yourself as “like a fish” when we first met.

Yeah, it’s like I’m swimming. You turn, and then—boom. Boom, boom, boom.

You’ve talked a little bit about this, but there’s this appreciation for materials at play here. This relates to the “high”/“low” idea, but it's also—I keep looking at this bowl that's made out of a garden hose. It’s an exquisite, beautiful object, but it’s made with an industrial hose.

Yes, it’s made by a young designer—I don't know who. I just saw this, and I said, “This is one of the most beautiful objects. I want to have it.” And it’s green, so I put it next to this 1950s vase from the south of France and a ceramic cactus from Naples.

Let’s talk about upcycling and how “Take It or Leave It” is a means of giving new life to something.

Upcycling is now talked about in magazines and the media—blah, blah, blah—but this is what I’ve always done. And I do it more and more now. The 25Hours Hotel in Florence was the first time I did this kind of upcycling exercise in an industrial way, taking objects and furniture that had already finished their lives and giving them a second life—a second chance—to have another story. Sometimes, in this process, we give some touches of modernity by painting them, by changing their color, by adding textiles. This is a nice upcycling attitude, but also, sometimes, you don’t need to do anything. Just taking something out of its reality today and putting it in another world, on another side of the planet, is already an upcycling gesture.

It creates a new value.

Exactly. An object goes from “low” to “high.”

Can you share a specific example of upcycling in the 25Hours Hotel project?

The check-in counter is built with really low-value luggage. We made this crazy sculpture out of, like, four hundred pieces of luggage, fixed them together—they were collapsing on each other—and painted them so that you can’t really see that they’re bad quality. [Laughs] It’s quite spectacular.

I’ve never really framed it or thought about your work in this way—maybe a little bit with Tham ma da, which was partly about how this European level of handcraft and industry could be mixed with the things you find in the markets of Bangkok or Hong Kong—but I think that there’s also this idea where, when you enter one of your projects, and the 25Hours Hotel in Florence is a good example, objects that come from all over the world become extraordinary together.

Yeah, these objects call to me!

So, at the end of the day, what do you hope people take away from this exhibition?

Some consideration of: What is design’s job today? It has changed radically from when I started working. People are hysterical, talking about sustainability and the planet, but the only thing that’s really effective is to stop designing and producing. If we are really worried—if we are really convinced of what we are talking about—this is something we have to think about.

Again, we have two scenarios: My office is exactly the portrait. One activity is to design products, and the job, in the past, was very concentrated on the personality of the designer—[Ettore] Sottsass, [Achille] Castiglioni. Every year, they were doing things very differently, and the factories were following them, very keen on producing every year, each one a very different kind of product. These companies were small, and the market was also small, because it was not really the “world market” that it is today.

Today, all of these small companies have a very difficult time. And if they’re not so small, they have to work in such a way that they produce things that are good for them, not for the [reputation] of the designer. So, we as designers no longer work for our ego; we work for our factory clients.

This is very different from being a star or being a very well-known designer, and asking a company, “Can you produce my chair?” You know me well enough. I never design a chair just for the sake of it. If I have nothing to do, I go to the beach, I sleep, or I read the newspaper. “Sustainability,” blah, blah, blah, all these other things, are cares of the company. Otherwise it’s useless for them to work, if they don’t follow the “rules” of the market. And if I design for them, I have to design for them, not for me.

When I do interiors, it’s much more free, especially in the way we do them. I’m now doing a 25Hours Hotel in Porto. When I did [25Hours] Florence, they wanted this crazy theme, Dante’s Divina Comedia. I told them it was ridiculous, but it was a challenge, so I did it. That’s why I won the competition. There were seven architects, and each architect told them, “You are totally dumb.” Which is true. We all said the same thing, but they insisted. So what happened? The others tried to incorporate this crazy idea—somebody in a very intellectual way, somebody in a very elegant way. For example, in the corridors [of one proposal], you could see all the poetry written on the walls. I told my office, “Listen, if they want Divina Comedia, they will get an ‘Inferno’ room, they will get a ‘Paradise’ room. We’ll see the reaction.” So all seven architects go to Germany to present. Of course, no one wants to show their project to the other. Then, when I went inside, I said, “Well, you want Divina Comedia, this is the story!” One room was all red, like a boudoir. One of them said, “This is impossible!” I said, “Yes, but it’s also impossible to make this kind of crazy project in Florence.” [Laughs] Another man at the company said, “But this is perfect! It’s not your own house. It’s a crazy place to go for one night with your girlfriend.” They all laughed and decided there was no competition anymore. I like to say, “You want this? We’ll try!”

I think this more open approach can produce a new kind of vision, a new kind of attitude, a new kind of market. Why not?

I agree.

Can’t young designers do this without becoming miserable?

I think what you’re proposing is that, yes, you’re creating new objects, new spaces, but a lot of it is also rooted in existing materials, if not made entirely with existing materials. You’re taking cues from the things that you’re collecting, but you’re also looking at how to reuse something that already exists. I think most designers—

They want to buy their own chair, because they make royalties! And that’s okay. But we buy our own chairs only when we don’t find anything else for the project. When we don’t find what we’re looking for with any success, only then do I say, “Okay, call Gervasoni, send me one of those chairs.”

The question becomes, if all we have is this Earth—this one Earth—and we’re in this moment of late-stage capitalism, and all these things have been produced already, then why can’t we create new life out of the things that exist? I think, in a very simple way, that’s what this exhibition is about.