How Japan’s Most Important Textile House Weaves the Past and Present into Its Fabrics

There is something universally comforting—deeply intoxicating, even—about petting a soft, warm coat, deep with pile. Maybe it’s the velvety hair of a newborn; a well-worn sweater, woven loosely with feathery fibers that soothe skin; or the silken pelt of a resident cat. Novelist and author Haruki Murakami described the latter in a 2001 short story titled Fuwa Fuwa ( “fuzzy,” in Japanese): “I reach out to touch the fluffy, soft fur, gently run my hand over the broad nape of the neck, the chill rounded sides of the ears, until finally the cat starts to purr. So nice to hear.”

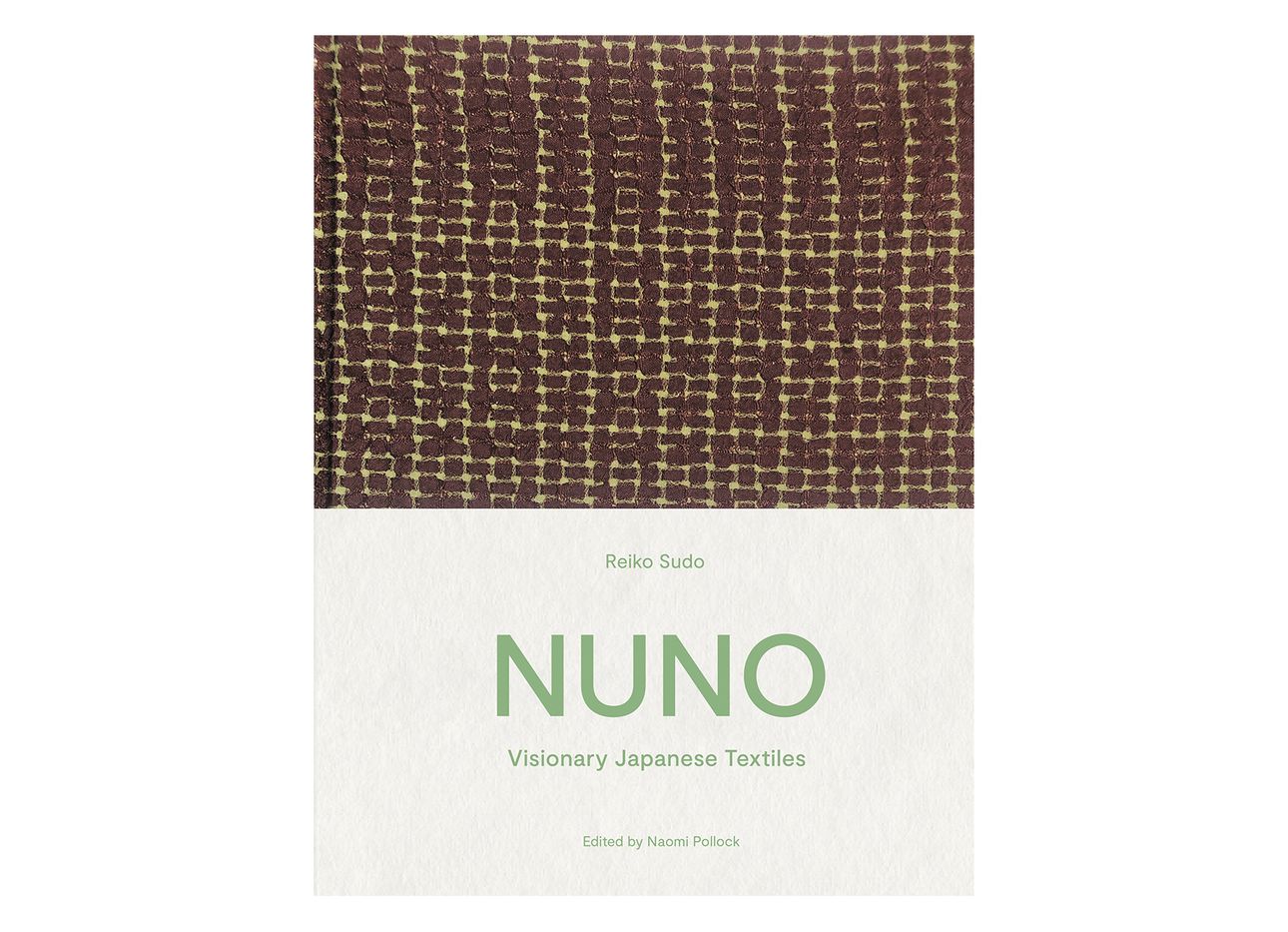

The essay is one of many inspired inclusions in the new book Nuno: Visionary Japanese Textiles (Thames & Hudson), a luscious deep dive into the history and imaginative output of the Tokyo-based textile house Nuno, which got its start creating avant-garde bolts of fabric with the likes of fashion designers Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto in the early ’80s. Founded by Junichi Arai in 1984 and led by managing director Reiko Sudo since 1987, Nuno (a Japanese word for cloth) has since crafted some of the world’s most innovative materials, honoring both the age-old traditions of Japanese textile workshops and new production methods.

Written by Sudo and edited by Naomi Pollock, an American architect who writes about Japanese architecture and design, the nearly 400-page book goes to great lengths to capture the Nuno team’s synapse-firing imagination and the deeply sensory creations that result. “For Nuno, standard weaving structures are meant to be reconfigured; the behavior of fibers, natural or artificial, is to be exploited; and just about anything, be it a rusty nail, dinner fork, or rubber band, can be a design tool,” Pollock writes in the introduction.

Each section that follows focuses on a specific type of Nuno textile, all named after an onomatopoeic term, and is enhanced with writings on the theme by creative luminaries and mesmerizing high-definition close-ups of various cloths. Fuwa Fuwa, the book reveals in its first chapter, is also the title of a gauzy, cloud-like textile family developed by Nuno with artisans across Japan over four decades and counting. Alongside Murakami’s essay, Sudo dissects the company’s numerous lightweight fabrics and tells intricate origin stories about their designs, often tying fabrics to the traditions—and even the fungi—of Japan. She explains that Shii Tree, a textile from 1997 with a plush red warp and seismic waves of black weft, was inspired by the tiger stripe–like wood grain of the tree it’s named for and the shiitake mushrooms that often sprout from the plant’s trunk; and that the 1993 textile Ice House riffs on sha gauze, an ethereal fabric historically used to make summer kimonos, by plumping it with alternating strands of wool yarn and cotton tape. Other chapters include Shiwa Shiwa (wrinkled), with an essay by designer Kenya Hara; Zawa Zawa (noisy), with four poems by musician Arto Lindsay; and Suke Suke (sheer), with an essay by architect Toyo Ito.

Some of the book’s most delectable glimpses into Nuno’s process arrive subtly in captions for the images. Readers learn that the 2006 fabric Baby Hairs, for example, is forged from fibers primarily used for safety devices and laced with phosphorescent pigments that store sunlight to glow in the dark. Hairball, a chunky sportswear pile knit developed last year, is steamed, trimmed, shaved, and brushed multiple times “until the fur comes alive.” And the industry-changing Jellyfish—a puckering, semi-translucent polyester organdy from 1993—is created by screen-printing areas with special adhesive, then flash-heating them to cause shriveling where adhered.

Near the end of the book, Sudo explores Boro Boro (ragged), Nuno’s collection of fabrics that have been cooked on burners, dissolved with acid, boiled, stewed, or shredded as a means of celebrating the beauty of a well-worn material. The chapter demonstrates Nuno’s commitment to renewable textiles—and the innovative, delightfully puckish ways it works to achieve it. Fabric scraps from Nuno’s workshops, as well as waste from other industries (the tough outer surface of silkworm cocoons or feathers discarded by poultry farms, for instance), become fodder for the line. “We’ve burnt out felted years of wear and tear into new cloth. We’ve affixed bits of newsprint and shredded remnants to imprint the past onto the present,” Sudo writes of its designs. “Like threadbare heirlooms you just can’t throw away, [these] textiles tug at our hearts with a mysterious emotional warmth.” The same can be said of the book that tells Nuno’s rich, intricately layered story.