Ever Heard of Noh Theater? Our Primer to Three Major Productions Arriving in New York City This Fall

Two winters ago, I picked up a copy of Penguin Classics’ Japanese Nō Dramas, a volume of two dozen translations by Royall Tyler I’d been meaning to read since tearing through Yukio Mishima’s Five Modern Noh Plays a decade previous. I had moved into a New York City gem (an apartment with a fireplace), and with Covid cases skyrocketing and temperatures dropping, I decided that a winter fireside with a handful of centennia-old ghost stories (cat in my lap, or reading aloud to a friend) might carry me away from the pandemic—from Brooklyn, 2020—to somewhere entirely distinct.

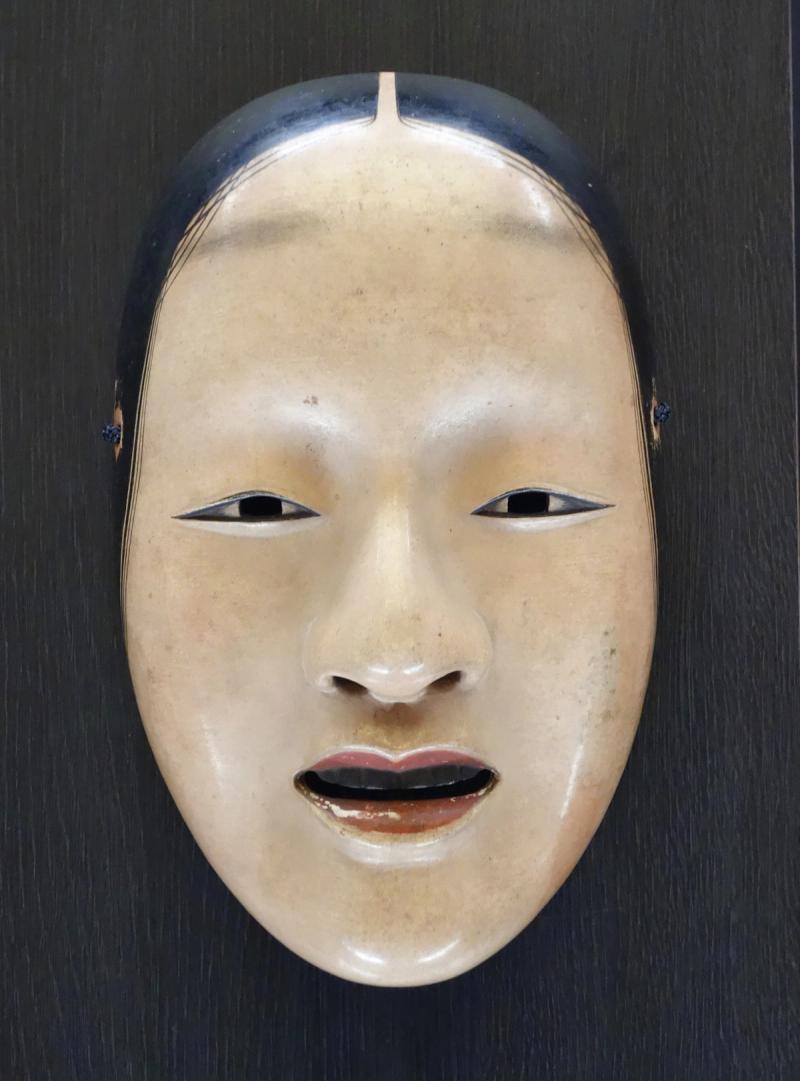

Noh is a classical genre of Japanese theater that originated in the mid-14th century and which now stands as the oldest continuously practiced theatrical form in the world. Both the form itself and the major body of plays were developed by two writers, Kan’ami and his son, Zeami. Designated an “Intangible Cultural Heritage” by UNESCO, Noh lies at the intersection of drama, dance, music, poetry, architecture, sculpture, and textile craft, an uncanny and electrifying convergence of ruthlessly precise acting, chanting, and physical movement inside shimmering silk costumes and intricately carved wooden masks that are artworks in their own rights. Many of these costumes date back to the origins of Noh itself. There are, for example, only a few hundred masks in existence, and each of the five Noh schools in Japan cycles through using theirs in different productions, decade after decade, and century after century—each line of actors, masks, costumes, and texts pointing back to a singular origin.

The plays themselves are performed with a near-excruciating control on a standardized stage with an on-ramp and and a painting of a single cypress tree, before a standard, L-shaped audience seating plan, with almost no set, and often only a single fan or small tree for a prop.

The stories that comprise the Noh canon also, by and large (though not always), follow the same eerie arc: 1) A visitor visits a place. 2) That visitor meets a local who tells them a story about that place. 3) At the end of their story, the local reveals that they are the person from their story, and then disappears. 4) Later that night, the local reappears in the visitor’s dream and reenacts the story through a dance.

Yoko Shioya, the artistic director of New York’s Japan Society, calls this distinctive approach to storytelling Noh’s “unique structure of phantasm.” The plays take place in a sealed seven-century-old conceptual box, but the worlds they evoke through a tight repertoire of conventions is so vast and immediate it defies human time. It’s as if Noh is outside time. There are few artistic forms as rapturously enthralling and slyly immersive as Noh, not least because the formal elements of performance are so refined they require a psychological, near-spiritual element of participation on behalf of the audience.

Consider that prop fan. Over the course of a play, it might become a sake flask, a warrior’s sword, a fish knife, a flute, or a writing brush. The shite (main actor’s) mask, meanwhile, communicates the character’s state of mind through the angle by which it is observed—tilted upward, the mask conveys joy or nostalgia; downward, it can convey despair, rumination, or pain. Actors’ movements are constrained by costume and stage limitations, as well as other technical matters, but the slightest gestures convey entire journeys across land, sea, and time, to the afterlife and back, a simple foot-dance sketching out mortal and immortal realms. The droll, monotonous chants of the singers are anything but flat; instead, the radical simplicity of each play’s dialogue, asides, soliloquies, and poetry—poetry often chanted between two characters in tightly controlled, cascading syntax—spills over from a kind of monotone foundation into the imaginations of the audience.

It’s often said, for lack of a better cultural reference, that Noh is “Japanese opera,” and while the combination of formal elements—music, voice, costume, and movement—is similar, the characterization is somewhat misleading on aesthetic terms. Opera is often unwieldy, bombastic, as big as its themes, while Noh enters the unconscious like a blade so sharp you only notice if you move.

Noh productions are rare outside Japan, but the form has had various foreign admirers throughout history (including, in the present day, the artist, jewelry-maker, and metalsmith Daniel Brush, who discusses his fascination with Noh on Ep. 23 of our Time Sensitive podcast). Says Shioya: “[Noh] influenced W.B. Yeats. Noh's economy of style in its drama and chanting speech inspired Benjamin Britten. The highly stylized body/dance movement of Noh performers influenced Robert Wilson. Noh masks inspired Turner Prize winner Simon Starling—just to name a few famous historical and contemporary artists. The uncompromising aesthetics of ‘less is more’ that you can see in Noh theater influences even more people beyond artists.”

One of these artists is Mayo Miwa, a New York–based performer and educator who received a traditional education in Noh before moving to New York and collaborating with artists such as Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alice Shields.

Miwa discovered Noh in her youth when her father took her to see a Noh performance at a gallery opening in Tokyo. “I've never seen that newness in my life,” she says. “[It was] super contemporary,” for a reason she couldn’t at first discern. That quality ultimately led her to apprentice under Sekine Shoroku of the Kanze School, and to major in Noh at the Tokyo University of Arts, before moving to New York and becoming vice president of the Noh Society.

Miwa says that part of Noh’s novelty comes from its blending of ritual and entertainment, and of the stripping away of some of theater’s common formal elements in favor of a “perfectly crystalized” simplicity that makes Noh’s themes universal. The actors, first of all, are more medium for experience than characters, Miwa says, “so the audience is, through the actor's movement, actually the center, and through the actor's body, the audience performs the performance.”

Meanwhile, the choreographic elements of Noh lend themselves to an open, rather than determined, experience of meaning. In Noh’s dance sequences, “it’s almost like there’s no story line,” she says. “It’s just dancing through abstract time, when the characters are immersed in waves of profound emotions. The audience is watching the performance, but at the same time, starting to think about themselves.”

“In Western theater,” she adds, “there’s a curtain dividing the audience and the stage. If you go to a Noh theater, there’s no curtain, there’s no division between the audience and stage. That means that the audience also goes into the experience, into the zone of time and space of Noh. After the performance, with no curtain call, the audience goes back to the empty nothingness. So the stage itself is just like the circle of the universe.”

Recently, opera organizations in Europe and the U.S. have been commissioning or producing Noh or Noh-inspired operas for local audiences, and this fall, a Noh-inspired opera and two traditional Noh plays will be performed in New York City.

The former is Hanjo, by Japanese composer Toshio Hosokawa, with a libretto by Yukio Mishima (one of his Five Modern Noh Plays, published in 1956). Directed by choreographer Luca Veggetti and conducted by Neal Goren, the founding artistic director of Catapult Opera, this North American premiere—taking place at N.Y.U. Skirball, with performances on September 30 and October 2—represents a rather nascent, cosmopolitan approach to Noh, via Mishima’s modernized adaptations. The resulting performance promises to expand the possibilities of the form for new audiences.

“The opera is not traditional—not by any means,” Goren tells me. “It’s based on a Noh first [created] in the fourteenth century, through the lens of the 1950s, and now through the twenty-first century. The themes—the role that dependency plays in love, denial, fear of the unknown, and need—are as alive now as they were in the fourteenth century. I think that’s what will appeal to modern audiences.” Goren adds that bringing Hanjo to North America is part of Catapult’s mission of disrupting, or expanding, the standard repertory of the operatic canon.

The second and third productions are of Kotei (The Emperor) and Makura Jido (Chrysanthemum Boy), and taking place December 1–3 at Japan Society and produced by the Kita Noh School, one of the five traditional schools of Noh in Japan, which was founded at the beginning of the 17th century and has been in operation ever since.

These performances present an unparalleled opportunity for American audiences to see the art form practiced by top-tier talents, and because of Japan Society’s focus on cultural education, to learn more about Noh and its history, no questionable self-translation needed. “To make the material accessible and deepen the understanding of American audiences,” Shioya says, “we created English subtitles from scratch.” An hour before curtain time, Tom Hare, a comparative literature professor at Princeton University, will provide a pre-performance lecture for ticket holders.

Shioya graduated with a degree in musicology from the Tokyo University of the Arts, and is deeply connected with many top-class traditional performers in Japan. She and her staff were kind enough to relay my questions to Takehito Tomoeda, a renowned Noh shite actor in the Kita School, winner of the Shogakukan Shirasu Award (2009), and a designated Intangible Cultural Property in Japan. They then translated Tomoeda’s responses in return.

Tomoeda began by telling me a bit about the masks that will be used in the New York performances. After centuries of use, Tomoeda says, Noh masks are “not mere theater props, but rather a spiritually important element that helps a Noh actor to convey to the audience the ‘truth’ of a story. In contrast to modern acting practice, in which an actor should transform himself into a character, a Noh actor is ‘transformed’ into a character by wearing a mask on his face. Such impact requires Noh actors to diligently train their inner strength in addition to acting techniques.”

Tomoeda says that this diligence in attending to the soul of a text is a central reason why Noh has survived the centuries. “Noh masks, costumes, chorus verses, and musical accompaniment—all are there to evoke souls. Restraint of expression is a methodology so that the performer’s acting does not overpower the soul of the words.”

In terms of the two particular plays this fall, Tomoeda says that Kotei is about curing an illness. “The mask used for the demon that causes the Empress’s malady is called ‘Shikami, which you can think of as the origin of the word shikame-tsura, or frown. It has deep creases between the eyebrows, with wide-open eyes and bared teeth, as if ready to bite at any moment. On the other hand, the mask used for the Emperor’s guardian deity that fights against the malady is called Ko-beshimi. The word beshimi means ‘closing one’s mouth, holding a deep breath to preserve power inside one’s body.’ As its name implies, this mask expresses the mighty power to stand up against a demon. The existence of a superpower beyond humankind’s abilities is the main theme of this Noh play.”

Makura Jido, by contrast, revolves around themes of youth and mortality. “The mask used for the boy character who has lived for seven hundred years is called Doji,” Tomoeda says. “The mask is made to be a boy’s face but with a hint of femininity, expressing a somewhat lonely disposition. This complex expression implies both the blessings of longevity and the solitude of living for seven hundred years. The costume for the malady demon in Kotei and the boy in Makura Jido share the same cut [shape], worn in the same manner. However, with different fabric patterns and colors, even the same costume design can transmit a completely different atmosphere. The pattern of the costume symbolizes each character in each piece.”

Tomoeda says that the school has already begun preparing to present the two plays with the highest fidelity possible. The major challenge, he says, will be to convey the soul of the play’s language, musical accompaniment, and dance movements to new audiences. But there are also technical matters to attend to. “Fortunately, Japan Society can provide kagami-ita, wooden back-panels with a picture of a pine tree, which is a symbol of the Noh stage and something that all Noh theaters in Japan are equipped with,” he says. “Also, the Society’s stage floor is smooth and natural wood, which enables us to do the unique Noh movement of suriashi [a subtle movement of sliding across the stage on one’s feet].”

But despite a rather rarefied reputation and set of conventions, Miwa notes that new viewers of Noh should simply enjoy the time and space. “In Noh,” she says, “immobility is mobility, where, with sound, the most profound sound is the inaudible space between sounds. This space [contains] a limitless expression that you can feel with your own imagination. It’s not that Noh is a passive form—it's an interactive art, where in a slow motion dance, time [can be] stretched several hundred years. But [viewers] can just enjoy the time in a way that people cannot in daily life.”

As for the future of Noh, Miwa believes that “we have to introduce Noh to a wider audience, especially young people.” She also suggests that the male lineage of actors in traditional Noh schools may change in order to preserve it. “The form itself is based on a man’s physicality. For example, the key of the voice chanting is much lower than what we have for female actors, Noh robes are extremely heavy, and it is challenging for women to see through a Noh mask. So, yeah, I think it should be more open to women—the form of Noh should be shifted a little bit or created for female actors.”

Tomoeda’s take? “In the twenty-first century, our great challenge as Noh actors is how we successfully hand down the form of Noh theater that contemporaries have always appreciated throughout every age and era.”

“Noh theater has been passed down for nearly seven hundred years,” he says. “The stylization and forms have inevitably evolved.”

One need look no further than Miwa, Goren, Hosokawa, and Mishima to see this evolution—and through it, Noh’s continued perseverance and preservation—in action. Don’t sleep on this chance to see it for yourself.