The Incredible Past and Pivotal Future of the New York Public Library Picture Collection

Since 1915, New York Public Library users in search of visual information have consulted its Picture Collection. It consists of images cut from magazines, catalogues, and books, each glued to backings and organized into folders encompassing a remarkable range of topics—including Praying, Transgenderism, Fairies, Oxygen, and Rear Views—that are presented on shelves in Room 100 for anyone to browse.

Used by journalists, historians, filmmakers, advertisers, designers, and even the U.S. military, the collection has been an invaluable resource for creatives of all types and stripes: Andy Warhol borrowed countless images for inspiration and never returned them; production designers for Saturday Night Live used it to source images of submarines, caves, and 1920s Harlem. Thanks to Romana Javitz, who became superintendent of the collection in 1929 and advocated for diversifying its contents, the assortment also includes often-overlooked subjects, such as folk art and portrayals of Black American life, and images taken and donated by such photographers as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. Taken together, the contents form a strikingly diverse, century-long visual timeline.

In the age of the internet, the collection’s format offers an increasingly rare opportunity for physical browsing—slowly, intentionally sifting through the pages, maybe encountering images you didn’t know you were looking for—and for human choice (unlike a Google image search, where an algorithm produces the most popular visuals for keywords). The serendipitous, multisensory experience of using the Pictures Collection is perhaps more important now than ever.

That’s why last month’s decision by library administrators to archive it by early next year struck a chord. Its plans to make access to the images available only by request, effectively eliminating the impromptu browsing of their folders, and to stop adding new images to the compendium, followed conservators’ feeling that the collection would deteriorate through wear or theft. (Digitization of the collection is not possible due to copyright law.) But last week, following outcry from supporters, the library changed course, and said it would keep the collection open and browsable by moving it to a new location on the first floor that will tentatively open in 2022. The controversy illuminates an ongoing, underlying question about the status of the collection: Is it a public resource of cultural ephemera, or a precious archive that needs to be preserved?

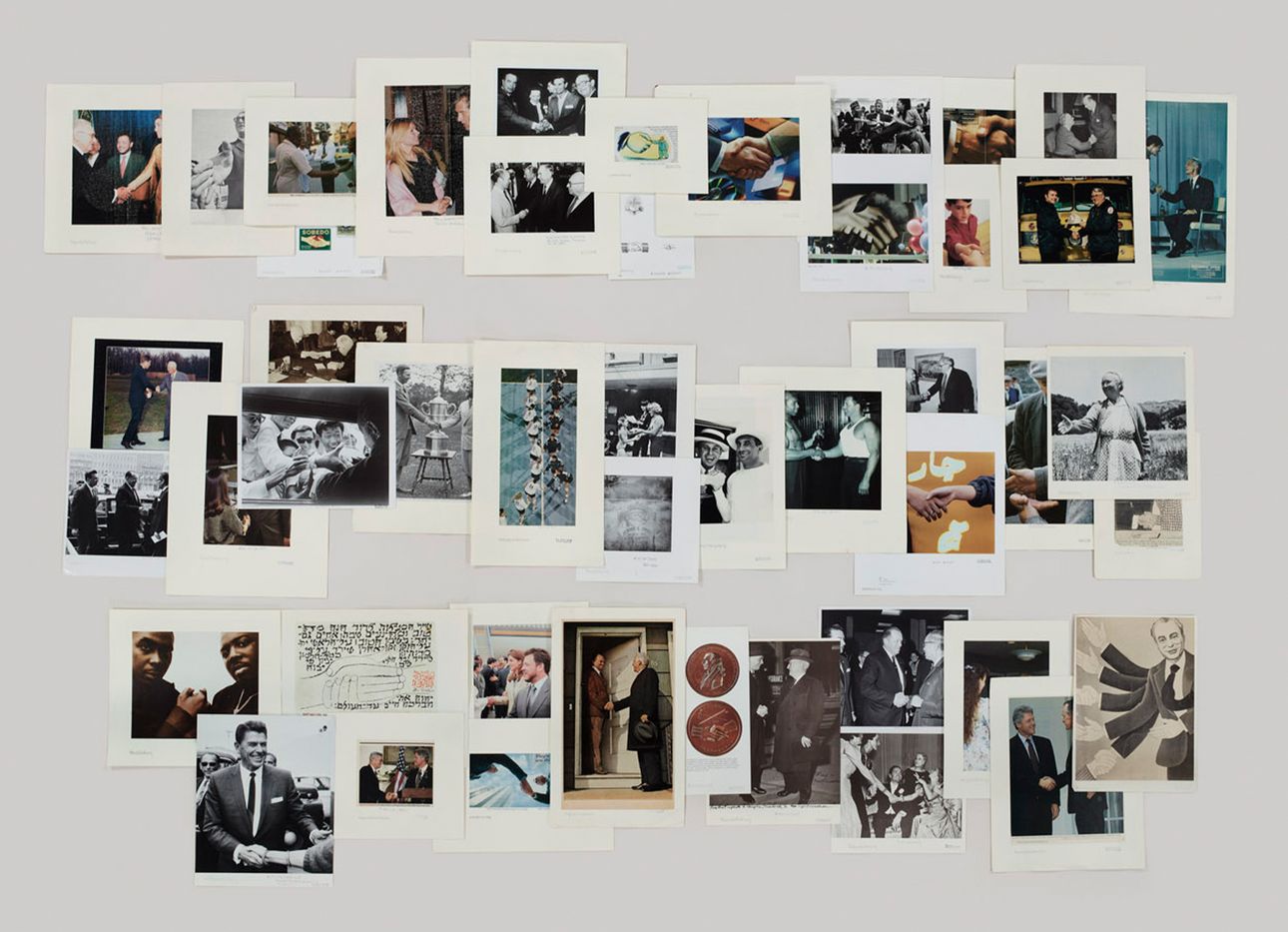

One view of the Picture Collection’s enduring value is evident in artist Taryn Simon’s coincidental exhibition, “The Color of a Flea’s Eye,” on view from September 23 through January 9, 2022, at the library following a stint at the Gagosian gallery on Madison Avenue. Titled after a patron’s request from 1930, the show features large-format photographs Simon took of images from the collection’s folders, which she arranged in layered, collage-like rows. The project, which took nine years to complete, is documented in a corresponding monograph.

Like the Picture Collection, Simon’s photographs invite viewers to draw their own conclusions when looking at her images. In doing so, one might recognize how the visuals inadvertently illustrate changing social mores, trends, and ideas around issues such as power, race, and gender. As the collection’s future unfolds, Simon’s work places its contents in a new light and makes a case for rethinking how to best honor and preserve its legacy.