As Art Basel Turns 20, Miami Art Week Enters a New, Slightly Less Hyped-Up Dawn

That the first work of art I saw during this year’s Miami Art Week was a newscast seems somehow appropriate in our precarious-yet-emerging-from-Covid present. “How do we make sense of things in today’s age of misinformation and sped-up media ecosystem?” the artists behind it, from the civic-engagement coalition For Freedoms, appeared to be asking. “And really, what’s the difference between art and the news?”

Just beyond the entrance to this year’s Untitled Art fair was the installation “For Freedoms News,” a project billing itself as a “creative experiment in artist-run media.” Playing off the seemingly official appearance of a CNN-, Bloomberg-, or Fox News–style broadcast set, the effort featured a community of artists, dealers, fairgoers, and others—from the poet Aja Monet to the reporter Marisa Mazria Katz to the digital strategist JiaJia Fei—in conversations around art, politics, and society. Coy as it may be, the entire concept made a compelling case around the performative nature of both the art market and broadcast media, as well as who shapes “reality” and who has the control to elevate particular voices.

Says the artist Hank Willis Thomas, a co-founder of For Freedoms, on next week’s episode of our Time Sensitive podcast (out Dec. 7): “We realized, in part from watching the news, that nobody knows what the news is, so why don’t we be the news?” Artists, as “For Freedoms News” illustrates, can function not only as profound storytellers, but also as their own kinds of reporters, journalists, and broadcasters. The project subtly argues that art can—and should—be a tool for giving people a moment to stop and reconsider what they see and hear in the day-to-day thrum of their media intake.

As is typically the case, the main news from Miami Art Week comes largely from the Art Basel fair, which—founded in 2002—turned 20 this year. (The fair’s anticipated first edition, in 2001, was delayed following 9/11.) Realizing its largest edition ever, with 282 galleries, Art Basel now has Noah Horowitz in a new position, as chief executive, with Marc Spiegler, the fair’s global director, departing after 15 years at the helm. It’s a shift in leadership that expresses, intentionally or not, a new dawn as the fair moves beyond its excitable teenage years—a hyped-up 2010s that brought about a frenzied confluence of satellite fairs, branded pop-ups, and celebrity-tinged parties—and into a more mature and slightly less amped affair. Following a decidedly more toned-down, masked-up edition in 2021 (due to a wave of the Omicron variant), this year there seemed to be a sense of mask-free glee, but also an ever-growing feeling of fair fatigue.

Remarkable as so much of the work on view is, the fact remains that Art Basel is, at the end of the day, organized around temporary white walls, in a big-box South Florida convention center, under industrial sodium lights. The setting itself is not all that sexy or exciting. (Still, much of the work is exceptional and museum-level.) Beyond any frills surrounding the fair, it remains primarily a place to present—and most importantly, sell—art.

Aside from a prankish “ATM Leaderboard” installation at the Perrotin booth from the Brooklyn-based outfit MSCHF, which gaudily displayed the cash balances of anyone who used it, as well as an at-this-point-rather-expected aerial drone “performance” from Studio Drift, what the fair seemed to lack was a theatrical or “felt” sensibility—or what the designer Alberto Biagetti, of the Milan-based studio Atelier Biagetti, calls “experiential.” “Installation is the word,” he told me over breakfast at the Miami Edition hotel. His partner, the artist Laura Baldassari, added, “Art Basel should feel like entering into a movie.”

“It should be delightful,” Biagetti said. “It needs a director coming from the movie business, from Hollywood.”

“Spielberg!” Baldassari said, through laughter.

Across the four fairs I attended—Untitled, Art Basel, Design Miami, and NADA, in that order—I noticed several post-pandemic threads, if not trends, emerge in the work on view. In particular, there was a lot of reaching, or grasping even, for a comforting sense of tactility, something that’s not all that surprising after various states of lockdown and social distancing over the past two years. At Untitled, this reached a crescendo at the booth of the Istanbul-based gallery The Pill, in the form of a painting by Apolonia Sokol depicting an intimate, orgy-esque group of 20 people—one in a bunny suit, another with long green hair, a central high-heeled figure in the nude—and a black cat, all clutching and cuddling each other closely. A particularly evocative sense of touch could also be found in the abstract photographs of the Japanese artist Daisuke Yokota, at Untitled’s Casemore Gallery booth; and at Art Basel, via an Uta Barth print, “Deep Blue Day” (2012), of a hand gently caressing a translucent white curtain, at the Tanya Bonakdar booth, and Kevin Beasley’s triptych “Cottonwood (From the Grove)” (2022), at the Casey Kaplan booth.

At Design Miami, the showstopper was a sculptural, hand-carved armoire-bar by Christopher Kurtz, at the booth of London’s Sarah Myerscough Gallery. Standing in front of the cabinet’s billowing angel’s wing-like poplar doors, Kurtz told me that the piece served, for him, as a deep philosophical excursion into not just the many implications of Covid-19, but pandemics past more generally. “I started looking at a lot of the Medieval, perpendicular-style architecture, and how that became stripped down and devoid of ornament, because the first people to die were the craftspeople,” he said, referencing the Black Death. “Gothic became more austere, vertical, parallel lines. That austerity was a way out of the bleakness of the situation.”

He noted that the notion of “masking up” became a chief consideration for the piece, too. “We’ve been covering our faces, draping ourselves, sheltering in place, holing up in our homes. So that’s where this almost—it’s not true linenfold carving, it’s not true trompe-l’œil illustrated carving, but it’s definitely referencing some of that in a more expressive, personal way,” he said. “The things that we cover also accentuate the things that we don’t cover.”

Calling the coffin-like result a “jubilee of a drinks cabinet,” Kurtz added, with a smile, “The Roaring Twenties came out of the [1918 Spanish flu] pandemic. It’s a hopeful piece. It can be macabre, but also celebratory.”

When I told him it could be viewed as “almost a home-bar memorial,” he replied, “Yeah! It is! I’ve been thinking about it exactly like that.”

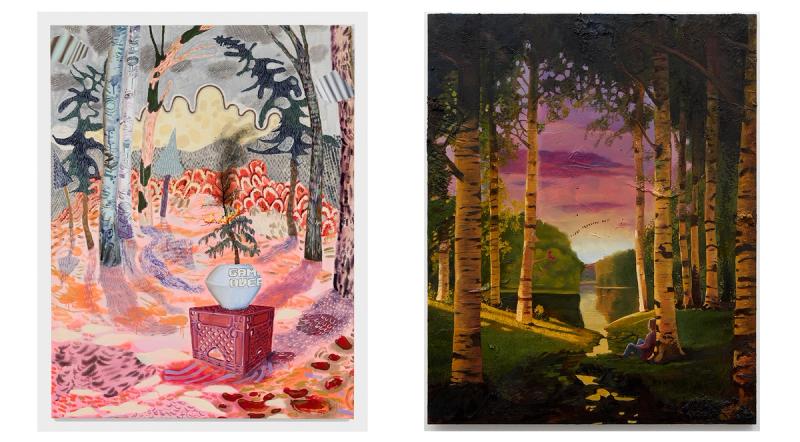

Now that we appear to be entering the “first post-pandemic winter,” much of the art created during Covid times is increasingly coming to light, and with it, a yearning for utopia or natural, Edenic idyll. Paul Verdell’s painting “A Road to Glory” (2022), at Library Street Collective’s booth at Untitled, and Doron Langberg’s “Ilan’s Garden” (2022), at the Victoria Miro booth at Art Basel, were standouts. (The latter was the most exquisite thing I saw all week, perhaps aside from a rare circa 1943 Isamu Noguchi “Lunar” light sculpture, once owned by Andy Warhol, on view at the Pace gallery booth.) At Design Miami, the radical Italian design company Gufram presented “Shroom Cactus,” a “utopian forest” installation featuring limited-edition items designed by A$AP Rocky. In addition to a modified version of the brand’s original 1972 Cactus sculpture by Guido Drocco and Franco Mello—A$AP Rocky’s has mushrooms sprouting out of it—the brand also presented a 3D-printed body armor–style suit by the musician. Two other landscape paintings of note—one, “Little Flame” (2022), by Melanie Daniel, at Asya Geisberg Gallery’s Untitled booth, and Friedrich Kunath’s “1-800 Serenity Now” (2022), at Blum & Poe’s Art Basel booth—each explored utopia in their own, darker way: through the thin divide between a seemingly serene countryside and a dystopian reality.

Stripping the notion of utopia all the way down to its most raw, literally skeletal essence—and in a nod to our age of late-stage capitalism—was a new work by Hugh Hayden at Lisson Gallery’s Art Basel booth. Called “Eden,” it features two intersecting wood-carved rib cages mounted on hangers, resting on an industrial steel clothing rack.

To those paying attention, not-so-subtle Covid-era messages appeared all around: At Untitled, just past “For Freedoms News,” were two pieces expressing a pretty on-the-nose, “everything is going to be okay” sentiment. One of them, by Lakwena Maciver, a large, boldly graphic, rainbow-colored tapestry (an art form that, as I’ve written for Town & Country, is back en vogue), declared in all-caps letters: “NOTHING CAN SEPARATE US”; the other, a spinning, touchable, stainless-steel sculpture by Amanda Keeley, titled “All Is Well, All Is Well, All Is Well” (2022), tried to offer reassurance while also looking oddly, or perhaps intentionally, like a branded pharmaceutical kiosk.

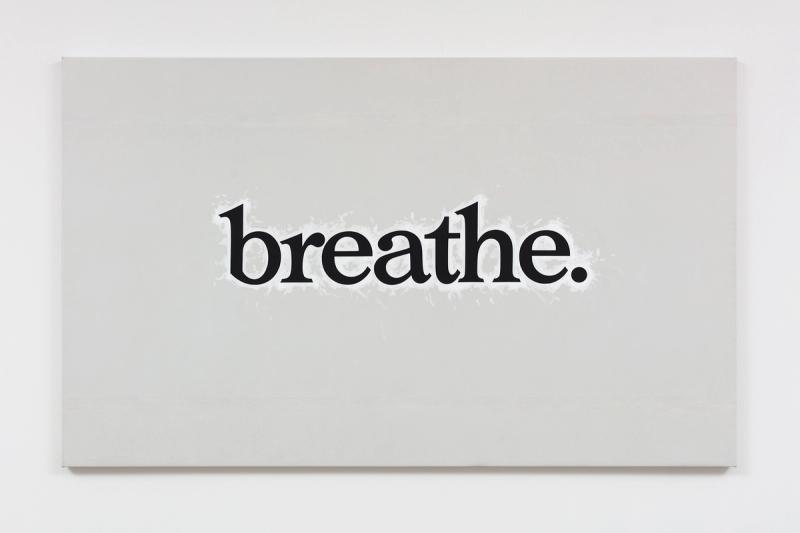

At Art Basel, in the Andrew Kreps booth, an all-white Ricci Albenda painting with black text commanded simply: “breathe.” At the Bortolami booth, three banners by Renée Green, expressing a sense of time warp, read in all-caps type, in this order: “WHAT TIME IS IT”/“ON THE CLOCK”/“OF THE WORLD?” The gallery Luhring Augustine, in an artful sprinkling of metaphor, presented “Guilt and Fear” (2022), a set of porcelain salt and pepper shakers by Ragnar Kjartansson shaped like a pair of monumental cemetery obelisks and with those words debossed.

Elsewhere, certain works captured the idea of viewing the world at a distance—and through window panes—including, at the Kates-Ferri Projects booth at Untitled, a series of airplane-view paintings by C.J. Chueca and, at the Art Basel booth of Sprüth Magers, Andreas Schulze’s painting “Untitled (Window Bassano del Grappa)” (2022), which was hung high on a wall, requiring viewers to crane their necks up to see it.

Connecting so many of these strands—tactility and touch, a utopic feeling, and a sense of play—were, over at the new Design District showroom of the Italian furniture company Paola Lenti, a series of handcrafted art-furniture pieces by the Brazilian designers and brothers Humberto and the late Fernando Campana. (Fernando passed away just two weeks ago, on Nov. 16, at age 61.) Comprising a variety of organic shapes and in the philosophical vein of a Noguchi playscape, the works, made of upcycled materials, look as if straight out of The Very Hungry Caterpillar 1969 children’s book. “This furniture collection connects with affection, with love,” Humberto said, tossing around and tying together the pieces’ worm-like appendages with childlike joy as he slowly walked me through the seven-piece installation. “Nowadays, there’s so much hate. So let’s talk about love and affection. When you work with your hands, you do it with all of your heart. The idea here was to create something alive.”

Beyond all the fair sales and celebrity-party mishegas, this sentiment is what Miami Art Week, at its best, is really all about.