An Heirloom Masa Supplier Champions the Origins of the Historic Latin American Dough

Many people eat masa—the Spanish word for the maize dough produced from stone-ground corn and used for making corn tortillas, gorditas, tamales, pupusas, and other Latin American staples—with little or no idea that it represents a multibillion-dollar industry, one that relies heavily on environmentally damaging agricultural systems that strip corn of its flavor and health benefits. A game-changing player in the masa world, Jorge Gaviria is the founder and CEO of Masienda, a supplier of heirloom masa, corn, and beans, and the first to create a scalable market for the surplus corn grown by more than 2,000 smallholder subsistence farmers using regenerative practices across more than 30,000 acres throughout Mexico.

Before launching Masienda in 2014, Gaviria worked at upstate New York’s Blue Hill at Stone Barns (run by Dan Barber, the guest on Ep. 62 of our Time Sensitive podcast), educating diners on the sensory and environmental benefits of sustainable, holistic sourcing. While there, he realized that the Latin foods of his childhood were largely absent from the farm-to-table movement, especially with regard to masa. The more he researched its ancient origins and contemporary supply chain, the more he felt compelled to champion the humble yet historic dough, which he calls a “vital cultural bond stretching the length of the Americas.”

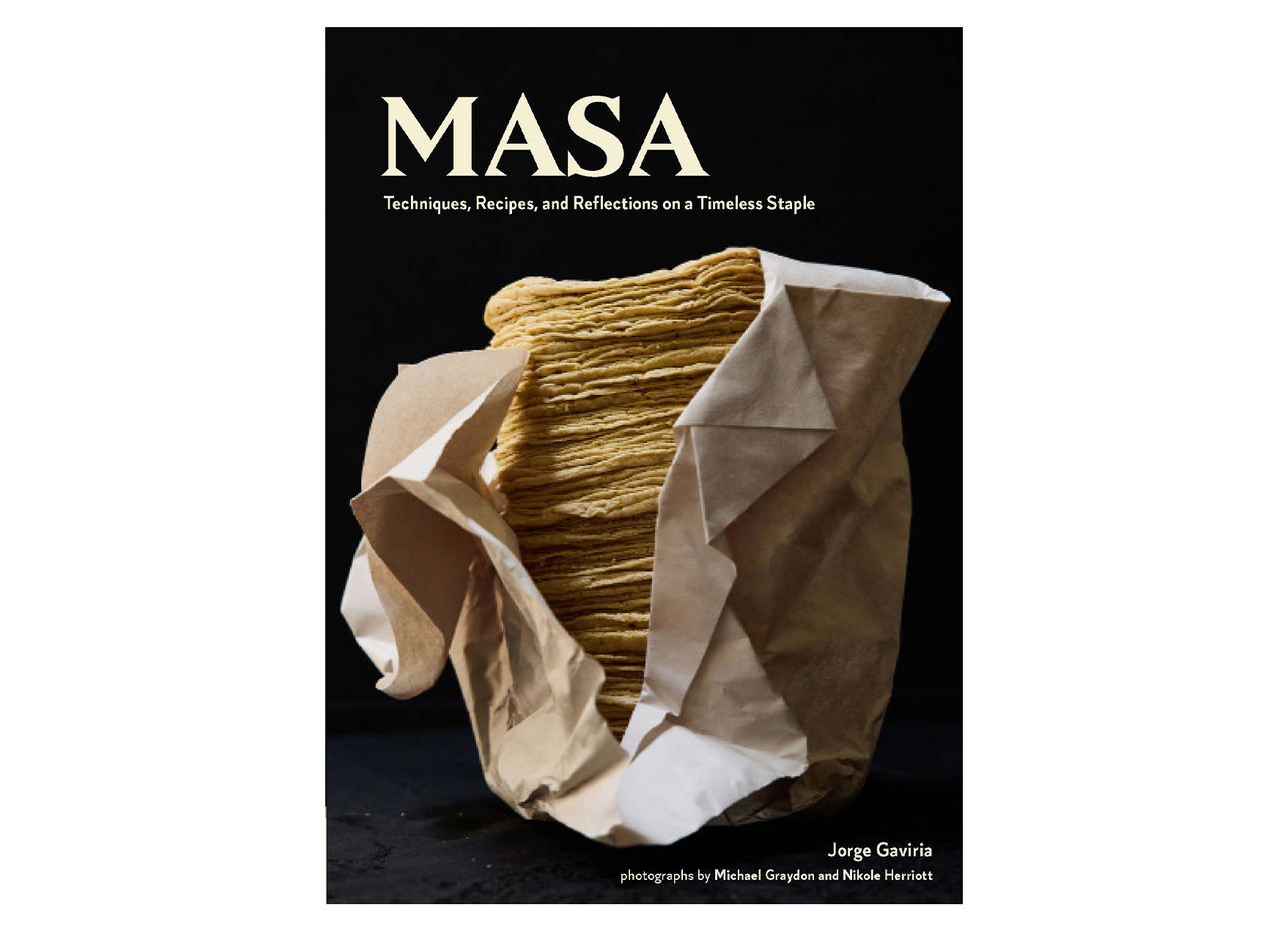

Out last week, Gaviria’s new cookbook, Masa (Chronicle Books), represents another step in the food entrepreneur’s quest to reposition masa within the milpa (corn farm) to mesa (table) conversation. Along with more than 50 recipes representing cuisines from across South America, Gaviria eloquently contextualizes the dough’s rich history and the fascinating science of transforming masa from dried corn kernels to complete dishes. We recently spoke to him to learn more about the local nature of the food, its vast cultural importance, and how to best optimize its flavor.

In Masa, you write about the “deep pleasure” you felt in Oaxaca’s Central Valley where farmers’ families effortlessly prepared tortillas made from their very own heirloom corn. Can you describe the taste of perfect masa?

In Oaxaca’s Central Valley, they grow an incredibly vibrant yellow corn called bolita. I took a bite of a raw kernel, and the flavor tasted like butternut squash and carrots, because it had retained beta-carotene and other valuable nutrients not bred out by the industrial process, which prioritizes yields and productivity over flavor and nutrition.

Up until then, for me the tortilla was a supporting character at any meal. In Oaxaca, I saw the tortilla really stand on its own. The best analogy is the feeling you get eating a perfect Paris baguette after a lifetime of eating Wonder Bread. Suddenly I was exposed to such a diversity of flavors absent from my childhood and even my adult experience. Nuances and flavors originate in the raw ingredients, then add to that preparation techniques and even how they’re served up. I became obsessed because all of these elements make such a difference in the pleasure payoff.

That first Oaxaca tortilla I tried had a sort of crustiness on the outside, but with a molten center, a similar contrast in texture that you get with the best baguettes. The flavor was compounded by nixtamalization [the process by which corn is steeped in an alkaline solution to draw out flavor and essential nutrients] that brought out an umami effect, with a little bit of sweetness, plus solidity and nuttiness. Fat in the corn kernel even lingered on my palate. The taste was profound, and I understood how farmers could take these tortillas into the fields and eat them on their own.

You write that corn and tortillas taste different in Oaxaca, with its thirty types of corn tortillas, than in Jalisco, or Chihuahua, or Yucatán. What is behind the taste variations?

Corn is a domesticated plant. It cannot exist without human intervention. What blew my mind was how regional the taste variations were—how much ecology and climate really inform the entire kitchen they support.

Across Latin America, corn presents as a spectrum: Some corn tastes incredibly dense, others floury. The kitchens and the recipe canons that surround the agriculture are directly related. Then you have special varieties, like colored corn, consumed more often to celebrate special occasions. The tortilla is linked to a natural product that looks and feels different in each native environment. Then you layer on techniques that over time have developed in response to their locations, and the results are remarkably different tastes. Sometimes, that creates division or local pride based on what each community knows and thinks of as the real thing. With this book, however, I wanted to celebrate all types of masa.

How would you describe masa’s importance in Latin American cultures?

As long as there’s migration, there’s cross-pollination in food, which you see in the twentieth century and earlier, but then at hyperspeed now with the internet and travel. If you go back to pre-Colombian deity worship, corn had a really symbolic meaning. Out of that history comes masa as we know it, making masa not Mexican, but also entirely Mexican. Masa doesn’t know borders; this one food item connects so many of us.

What ingredients and conditions, such as single origin corn, can optimize masa?

Masa is very simply made of corn, some kind of alkaline agent, and water, so you don’t have much to manipulate from an ingredient perspective. However, within each of those ingredients, there’s room to manipulate for flavor. Water changes hydration and cooking time, which affects flavor. It’s why bagels taste better in New York City than they do in Los Angeles. Corn is the biggest lever because you have so many microclimates—fifty-nine in Mexico alone—and these produce thousands of combinations. Ultimately, single-origin corn is more about connecting with place and process. Flavor can be so subjective and sometimes such an emotional experience; feeling connected to where your food is coming from makes the flavor taste so much better.

Unlike mass masa production, Masienda’s model of working with subsistence farmers prioritizes biodiversity in the growing process and naturally enhances the flavor. How would you describe that difference in flavor?

Mass masa will last longer on grocery store shelves, but ultimately with less taste, because preservatives affect flavor. Over the last fifty years, a lot of the thinking has been taken out of the process in favor of efficiency and scale, and there has been a movement towards the white tortilla, more wheat and less corn, because of a Eurocentric preference for wheat. But that consistency comes at the expense of all of the natural compounds with their nutrients. Ultimately, diversity just tastes really good.