Fifty Writers on the Albums That Changed Their Lives

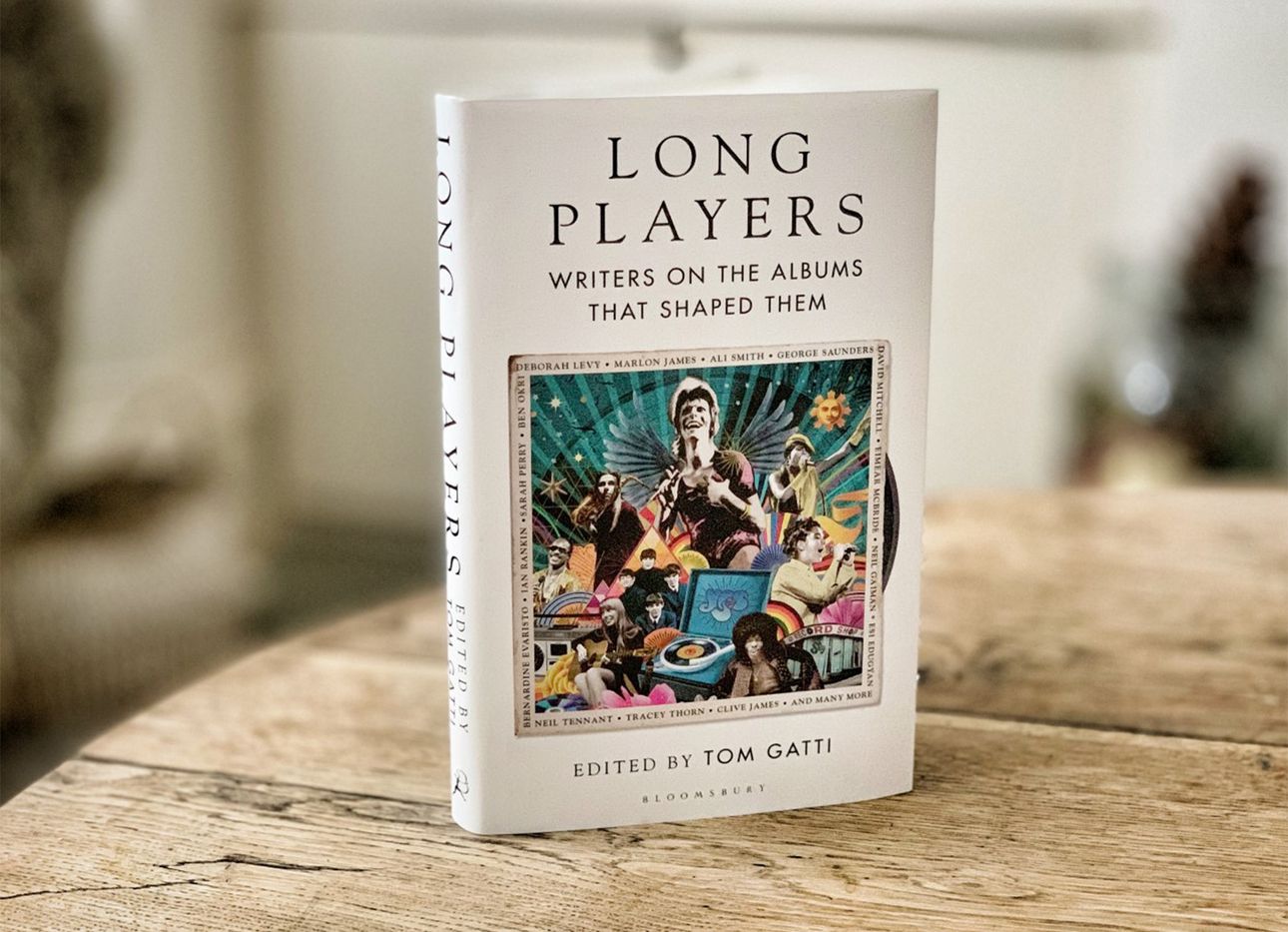

What is it about that one stirring album that makes a home in us? Tom Gatti, deputy editor of the British political and cultural magazine The New Statesman, investigates the mystery of such beloved recordings in his new book Long Players: Writers on the Albums That Shaped Them (Bloomsbury). In it, he sets the stage by navigating the album’s material evolution, from the golden years of vinyl to the streaming age, then passes the mic to the book’s fifty contributors—novelists, poets, and critics among them—who describe their encounters with their favorite euphonic compilations via short-form personal essays. Readers learn how R.E.M.’s “Automatic for the People” transports Olivia Laing to her first love, why Yes’s “Fragile” prompted George Saunders to forge his own creative path, and how Björk’s “Post” helped a young Marlon James resolve a crisis of sexuality and faith. Each composition blurs the line between memoir and music writing while demonstrating a song’s ability to carry a listener to another place and time.

We recently reached Gatti by phone in London to discuss the power of song, and why albums that move us stay with us throughout our lifetimes, often with an entrancing power that never fades.

Listening to music can be such an intimate, personal experience. How did you select the contributors, and were people open to writing about music that impacted them in this way?

There’s usually a fair amount of cajoling involved in trying to get writers to contribute to projects like this, because they’re invariably locked into much more important projects of their own. But as soon as I sent out requests for this idea of writing about a cherished album, the responses came back as soon as I pressed “send.” Pretty much everyone wanted to do it, and also knew quite quickly, I think, what their record would be.

One of the strands that goes through the book is how music informs not only one’s identity, but one’s creative identity. What I learned is: You can’t overstate how important these early encounters with albums are for people, and for writers in particular.

Many of the writers note that the albums they chose were discovered earlier in life, often during their teenage years. What is it about that period of time that opens people up to music?

The idea of that specific time of life is an important one, and in the book it coheres around the teenage experience. There’s a line from Deborah Levy’s piece that sticks in my head: She likens her encounter with David Bowie to throwing petrol on the naked flame of teenage longing, and a desire for a different life. There’s something particularly malleable about the teenage mind. You’re sort of primed for these [sonic] experiences, and they have a lasting effect.

There’s also a sense of continuity. These records can offer a nostalgic experience when listening to them again as an adult, and also can enhance the present moment. If there’s music that you’ve loved, when you pick it up again after a long gap, you realize this feeling: Somehow, somewhere, in all those intervening years, it’s been playing in the recesses of your brain. You’re just picking up where you left off.

Did any of the album choices surprise you?

Absolutely. Patricia Lockwood chose an obscure British indie collective called This Mortal Coil. She brilliantly captures the strangeness of listening to them while growing up in the American Midwest. Similarly, Tracy Thorn writes superbly about how her family’s divergent musical tastes were put together by Stevie Wonder.

Another pleasant surprise was—this is a bit self-indulgent, so forgive me—how many of my own formative records crop up. I grew up in the nineties, and as the choices came in, I started seeing Cypress Hill and Tricky’s Maxinquaye…. My friends are going to think I planted all these records in the book, but they happened organically. I wasn’t expecting to see Warren G’s “Regulate… G Funk Era” in a book of literary writing about the album, but I’m absolutely delighted it’s there.

What is it about music that enables it to lodge in our psyches?

Of all the stuff we absorb, it’s music and albums that we revisit through hundreds and thousands of listens. Particularly for my generation, and people a little bit older, with the advent of the Walkman, you were able to do that in a sort of solitary space. I spent hours of my teenage years sitting on buses, listening to albums. In that way, they can work their way inside you in ways that few other art forms can.

There’s also a real immersive quality that you get from an album that you can’t get from a mix tape, or a pop song, or other forms of music. You listen to a record from start to finish—as the artist intended—and they have a novelistic quality. They’re linear forms, and present you with an emotional arc, a journey. They create a sound world that you can return to as often as you like, and you have a subtly different experience every time, depending on your mood and the stage of life you’re in. In that sense, albums become your trusted companions.

Do you think that effect ever attenuates?

No, I think it’s lifelong. The way we interact with music changes over time and with age. But I think your enthusiasm for music, your hunger for new music, the intensity with which you listen to music, it all continues, undimmed. What you don’t have is that feeling of it being akin to falling in love the first time. It’s different, and in some ways better, later, but it’s never quite the same.

What’s striking to me is, when I discover something new now, the feeling I get from it is the closest I feel to my teenage self. It activates that sense of newness and discovery, and perhaps that does get a bit dulled over time. I called the book Long Players for a reason. I don’t think you’ll ever get bored of the records that these writers talk about, or the albums that shaped you. You might not listen to them for extended stretches of time, but you’ll never tire of them.