Botanical Artist Lara Call Gastinger on Seeing Scents

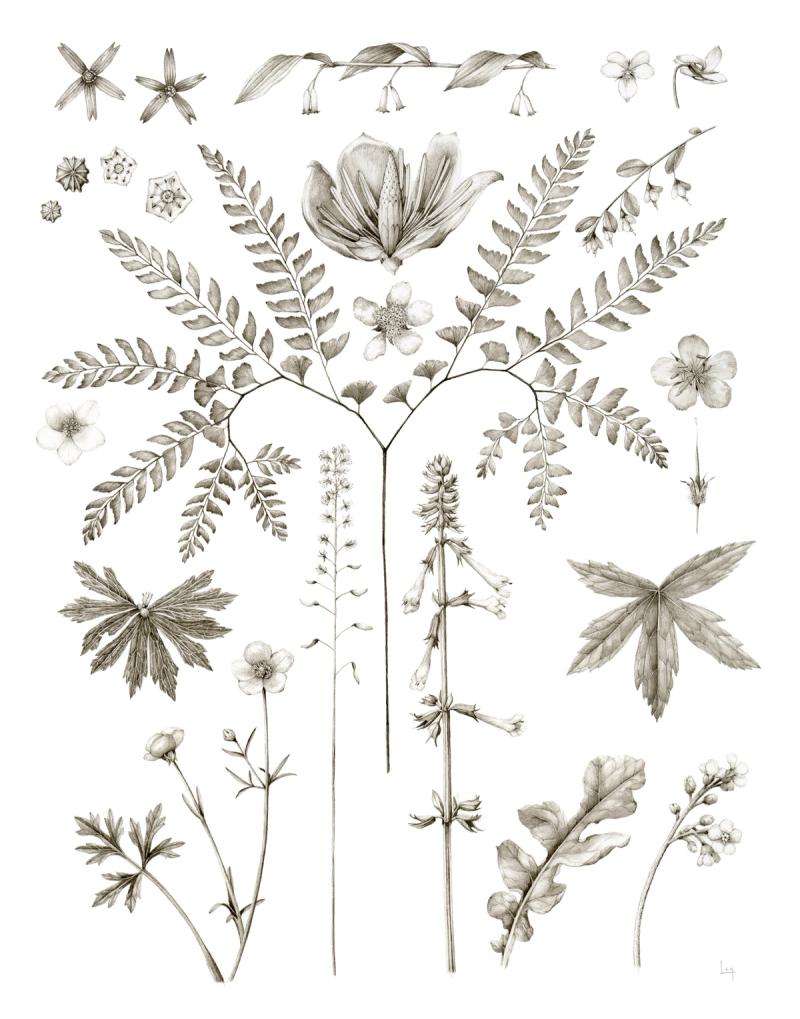

For botanical artist and illustrator Lara Call Gastinger, the treasures of fields and forests reveal themselves in a profusion of shapes, colors, and textures. Gastinger's meticulous drawings and paintings operate in continual dialogue with the natural world, drawing upon processes (such as fluorescence, dormancy, and decay) and plant structures (including roots, stems, and seed pods) that demonstrate a world of beauty that goes beyond just that which is simply in bloom.

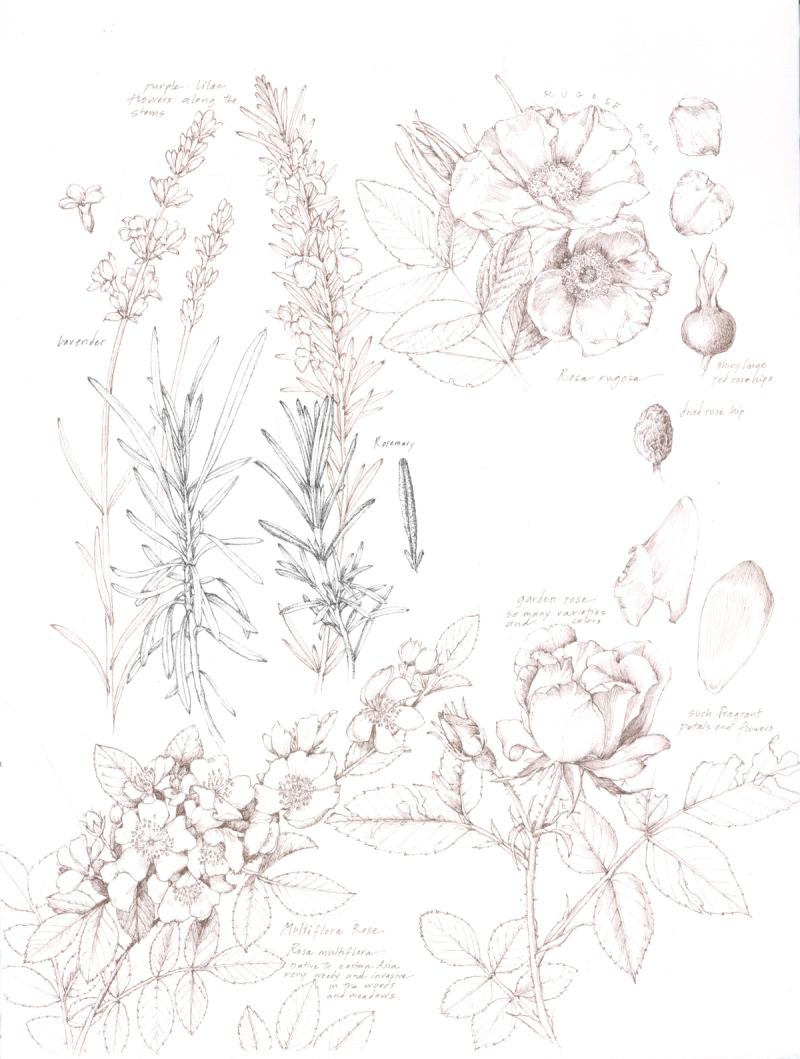

Based in Charlottesville, near the mountains of central Virginia, Gastinger’s practice began after she received a master’s degree in plant ecology from Virginia Tech. Poised to embark on a career of fieldwork, she instead pivoted when she learned of a role to illustrate The Flora of Virginia for the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, the first manual on native Virginia plants published in 250 years. Over the next decade, Gastinger went on to illustrate around 1,300 different species for the project, which was published in 2012. (An iOS app version of the volume featuring Gastinger’s illustrations is also now available.)

Today, Gastinger is a two-time gold medalist at the Royal Horticultural Society Botanical Art Shows in London (winning in 2007 and 2018, respectively), and she regularly teaches virtual and in-person classes on pen sketching, nature journaling, and botanical watercolor painting. She has been invited to teach an immersive botanical art class in Transylvania, and during the pandemic founded the Perpetual Journal project, which invites artists at all levels to begin a weekly practice of observing and illustrating their local flora. Since its beginnings, the Perpetual Journal has grown into an international community of nature drawers that connect through social media to share their work.

This year, Gastinger created exquisitely detailed illustrated accompaniments for Scent: A Natural History of Fragrance (Yale University Press) by biologist-turned-perfumer Elise Vernon Pearlstine. In the wide-ranging, 272-page book, Pearlstine traces fragrances from the cultivation of the basic aromatic substances that comprise them to their cultural implications. We spoke to Gastinger soon after her return from teaching a weeklong botanical atelier at Clos Mirabel near Pau, in southern France, where she led her students in the art of slowing down and looking closely.

How do you select your subject matter?

I only like to focus on native plants and plants that are “naturalized,” meaning they might be non-native but they’ve become established in that environment. Domesticated plants—plants in the nursery trade—aren't really of interest to me. It’s amazing to see what’s already there, what’s already put together, and in some ways, designed. Taking a walk in the woods is the best pick-me-up.

I don't paint everything or draw every plant, because they don’t all resonate with me. I don't know what it is, but the plant will just say “Draw me!” There are definitely things I focus more on: roots, vines, twisting things, seedpods, lichens, mosses, mushrooms. As a botanical artist, I rarely paint flowers. Instead, I like to paint things that people don’t see as much. There are so many stages of a plant that are so interesting. Maybe it’s an interesting leaf that has a hole in it. Those things really attract and resonate with me.

In your experiences teaching, how does working with plants impact students’ relationships to their surroundings?

With travel teaching, virtual classes, or teaching locally, I help people explore the landscape on a deeper level through basic botanical skills. It really helps people pause and be in touch with their environment, and to explore a place. It’s so important for me to teach people how to really see their landscape. One of the most important things—and I think about this with my kids as well—is that people are curious and observant, and are questioning. That’s what I want people to do when they go outside.

I’ve seen so many people start a perpetual journal, and it encourages them to ask these types of questions. Perhaps they’ve lived in their house for fifteen years, but they’ll say that using the journal prompted them to finally figure out what kind of tree has been living in their front yard all those years.

It sounds like those revelatory moments are less dependent on where you are in the world, and are more a matter of perspective.

I always start all my presentations with a quote from the late [biologist, naturalist, and writer] E.O. Wilson, who studied ants and coined terms like “biophilia.” He says, “A lifetime can be spent in a Magellanic voyage around the trunk of a single tree.” You don’t have to travel or go far—the tree in your backyard can produce enough to observe. It’s about learning to slow down and look and see in a different way, and ask, “What’s new today, and how is it different from yesterday?” Sometimes people get overwhelmed that they have to be good at drawing. The journal is not about being perfect; it's just about observing and paying attention and enjoying it.

How does your artistic practice affect your perception of time?

I get really excited during each new season for different reasons. Most of the time it’s to see the seedpod of something. Using the perpetual journal and knowing that the seasons will still come gives me comfort. There’s something comforting in the refrains of the seasons, seeing the same plants again and re-experiencing all of the sensations of each season.

I'll think, What do I have to look forward to next week? And then I'll look ahead in my perpetual journal and see. This just happened, actually. I was flipping through my journal and I saw that we’d picked chanterelle mushrooms last year, so I got really excited. I thought, It’s time to go look for chanterelles. It’s like seeing an old friend again.