Ghetto Gastro’s Jon Gray on “Durag Diplomacy” and the Beauty of the Bronx

Over the past decade, the Bronx culinary collective Ghetto Gastro has—through a combination of creative finesse, clever tactics, linguistic gymnastics, and food alchemy—risen up in the worlds of art, fashion, and entertainment, serving up a new, raw form of cultural ambassadorship. Unofficial representatives of their home borough, the group’s co-founders, Jon Gray (the guest on Ep. 2 of our Time Sensitive podcast), Pierre Serrao, and Lester Walker, practice what they call “durag diplomacy,” bringing the Bronx to the world and the world to the Bronx. The trio’s scope and impact is vast, from collaborating with French luxury house Cartier on a “Bronx Brasserie” pop-up in Paris, to launching kitchen appliances with Target, to cooking with Wolfgang Puck at this year’s Oscars. An unabashed gastronome and the group’s self-described “dishwasher,” Gray has the agility and energy of a frontman: Currently an artist-in-residence at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, he’s perhaps best known for his 2019 TED Talk, which has been viewed nearly two million times. Serrao and Walker are seasoned chefs with backgrounds in top restaurants, including at Cracco in Milan and Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s now-closed Spice Market in New York, respectively.

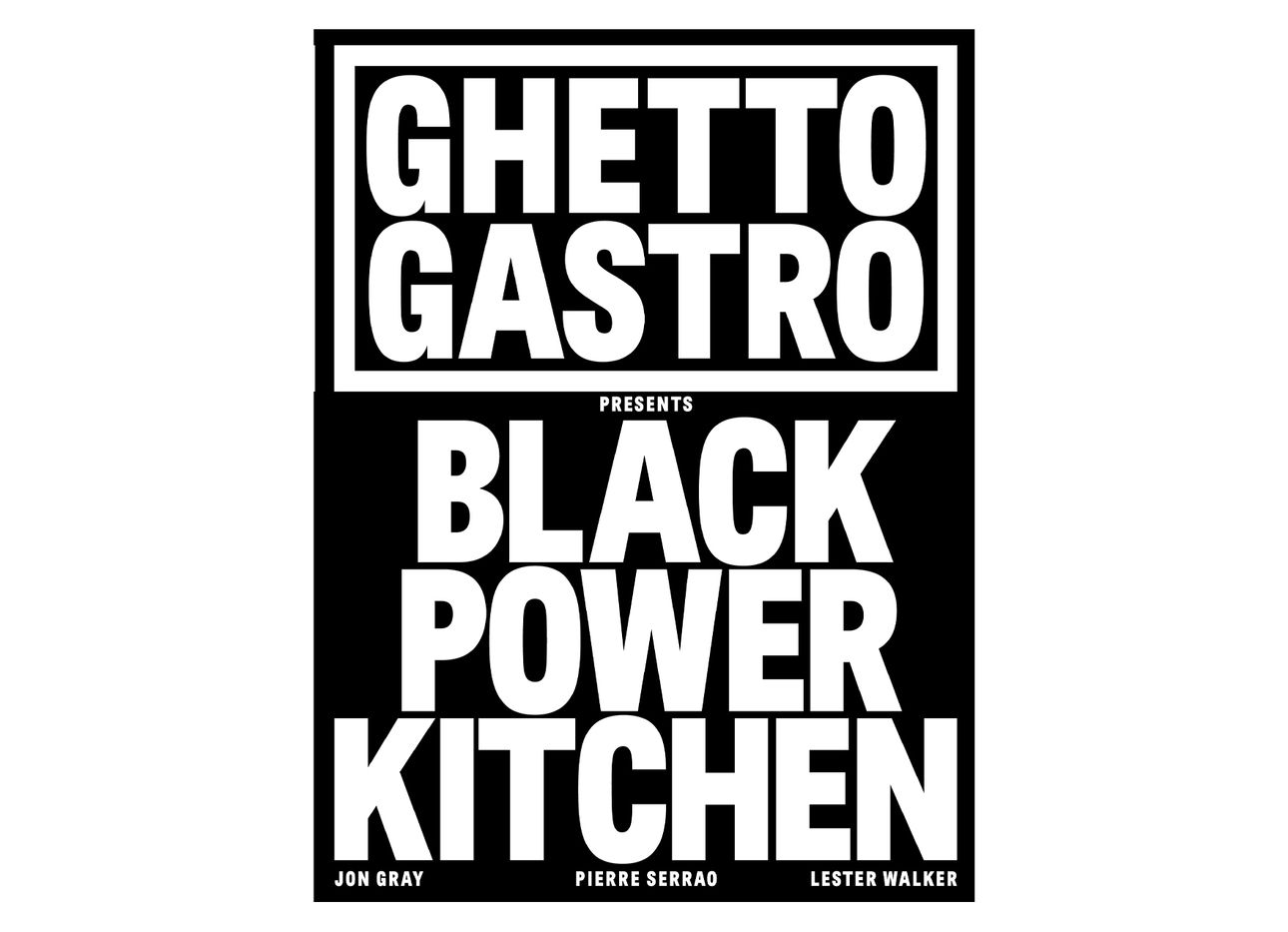

A new book from Gray, Serrao, and Walker, Black Power Kitchen (Artisan Books), culls together the collective’s rich bouillabaisse of ideas and recipes, functioning at once as a manifesto and a cookbook, and as one long ode to the Bronx. “Ten million dollars’ worth of game in a forty dollar book” is how Gray describes it. Here, we speak with him about Ghetto Gastro’s journey up to now, and why he views the group as “a vehicle for Black liberation.”

Let’s start with the fact that you came up with the name of Ghetto Gastro in February 2012, typing the phrase “Ghetto Gastronomy” into your iPhone’s Notes app.

I’ve got the evidence. [Laughs]

Share a bit about the name and its meaning to you.

I’ve always personally loved friction and collision, taking things that people don’t normally associate together, and bringing them together, and making it make sense. On a deeper level, we use the term “Ghetto Gastro” to highlight—not to highlight; to indict, rather—the systems and neglect that have created disenfranchised communities. I grew up in these types of communities, and have an intimate knowledge of the inequity, because I’ve straddled both worlds, being in the elite spaces through art, fashion, entertainment, et cetera, but then the reality of being back home in the Bronx.

You’ve reframed this idea of “ghetto.” You’ve basically made it a reclamation. Could you talk a bit about that?

Yeah, for me, it’s really an internal dialogue. Often, within communities that have been underestimated historically, we might not place the type of value on our expression as we should. When you think about the Bronx and the art forms that have come out of here, we’ve been creating value for other people for a long time, and now it’s time for us to coalesce, get together, and capture that value.

Was there a particular tipping point over the past decade when you knew Ghetto Gastro was going to pop the way it has?

When we did “Waffles x Models” in 2013. That’s when our friends in the industry—the kind of niche fashion/art thing—started to take notice of the project. And then, when we did our first international project, in the south of France, in 2014. So 2012 was just a lot of experiments and house parties at my apartment, and then we took it to the next level with “Waffles x Models,” and then with “South Bronx in South France.”

Some of the work I’m most proud of is the work we did with La Morada, via mutual aid during the pandemic, and especially with Sky High Farm. Doing stuff with the big brands is dope, is fun, but you gotta make sure you pay it forward.

Share a bit about La Morada for those who don’t know.

La Morada is a Oaxacan restaurant owned and operated by a family of undocumented immigrants and Dreamers, and they’re really big on liberation. They have a free library inside the restaurant, in addition to some of the best mole I’ve tasted on this side of the border. Just period, honestly—their mole is incredible.

During the onset of the pandemic, they sprang into action and started feeding families. Me and Pierre [Serrao] were in the Cayman Islands just watching, like, yo, we gotta help. Like, we can’t physically help from here, but we’ve gotta support this movement. So we just connected some dots, put some resources together, and fueled about close to a hundred thousand meals going out.

Incredible. And I have to say here that La Morada is the best mole in New York City.

Right. You know what’s up. I like the spicy oaxaqueño. I do it with the vegetables, and I get a side of the garlic shrimp, just mix it all up.

What have been some of the major challenges you’ve faced in growing Ghetto Gastro along the way? This project, at its heart, is about inclusion, race, access, and really how food and cooking can provide a sense of freedom and power. Can you speak to that? What have been some of the tricky parts of breaking in?

What some might perceive as challenges have been our superpowers. We didn’t start it strictly as a business, per se. It was more of a fun project. We didn’t have to make it make sense. We could just really do the things that mattered to our hearts. We did what felt right and took the project slow. And it has grown organically. It’s not like we were out here searching for clients. None of the work we do is outgoing; everything is incoming.

We’re also very expensive. And that’s intentional, because people think with their wallets. So when they now see Black people from the Bronx, when they hear the word ghetto, they might rethink how to use it.

There’s something almost punk about your approach.

Yeah, and we keep it like that. Because I come from a background of being an entrepreneur, I understand the value of economics. The revolution also needs to be financed. But we don’t put economics before our ideologies and our values.

Part of what you do is about education and, as you’ve called it, “durag diplomacy.” What have been some of the lessons learned? What has surprised you most about outsiders’ responses to the cultures and cooking of the Bronx?

Just the multitudes that exist here. Often, when people think about the Bronx, they just think about blight and pain and suffering. But it’s just got so much beauty. It’s such a diverse place. There’s so much to uncover, and we’re just happy to be unofficial ambassadors of the town.

Let’s get into Black Power Kitchen. What was your vision for the book?

Well, me, Lester [Walker], and Pierre, we just really wanted to approach this like, all right, if this was our first book and our last book, what needs to go in it? Also, we didn’t want to sound like pricks when people were like, “What’s Ghetto Gastro?” And then be like, “Here, see my TED Talk.” Now we can just tell them to get the book. It’s really just giving people the ideology, giving them recipes, food for the body, but also food for thought—curated selections of art from our friends and heroes. It’s just bringing all the pillars. The book’s basically the recipe of Ghetto Gastro: food, art, activism, Black culture. For us, it’s really just using our creativity as a vehicle for Black liberation.

The book features seventy-five recipes. What are some of your absolute favorites?

It’s hard to choose because I’m such a moody eater. I wake up wanting something different all the time. But if I had to choose right now, I’d definitely go with the Black Power Waffles, I’d go with the Twerk & Jerk [Chicken], and I’d go with the watermelon salad. Green juice, too. I’d get a green juice to round it out nice.

Design is a core component of the work you do. Could you share a bit about Ghetto Gastro’s approach to design overall?

We care so much about aesthetics. Just like how we use food as a language, design is a language. It’s a very important vernacular that we employ to get messages out. A lot of people don’t read, so the visuals have to be striking. We like to be able to use that as a method to grab people and pull them in. We’ve been collaborating with New Studio for years. Our collaboration with them allows us to evolve in a natural way—and a surprising way—to keep people on their toes and not know what’s coming next. It’s consistently inconsistent.

How would you describe the Ghetto Gastro aesthetic?

Man. [Pauses] It’s a Black Power aesthetic. It’s like Black Power in 2050. We use the Pan-African colors. We just try to reimagine, What’s bad and bold? It’s really our personalities and ideologies, in a visual sense.

Can you share anything about what you’ve got coming up?

We’ve got the book tour going crazy. Products, man. We’re expanding the business. We have the air fryers and appliances from Target. And what we’re really going to crush, and what we’re really excited about, is Ghetto Gastro foods. Starting with our [Wavy] waffle mix—you just need to add water, nutmeg, whatever you like to use. And we’ve got the Sovereign Syrup, a spicy, spicy syrup—apple cider syrup, maple syrup, made with chiles. It’s incredible.

Then we’ve got some other surprises up our sleeves. We recognize that a lot of people don’t get to experience Ghetto Gastro in 3-D, from an experiential perspective. But we want to create a lane where people can really open it up. We don’t want to be exclusive with a capital “E”; we want to be inclusive with a capital “I.”

And this book is a big part of that.

Indeed. We’re giving people the tools to make it happen. I like to say, it’s ten million dollars’ worth of game in a forty dollar book. Ain’t no room for halfway crooks, ya dig? Get the book and cook, son.