A New Book Captures the Magnificent Breadth and Melancholic Beauty of Alec Soth’s Photography

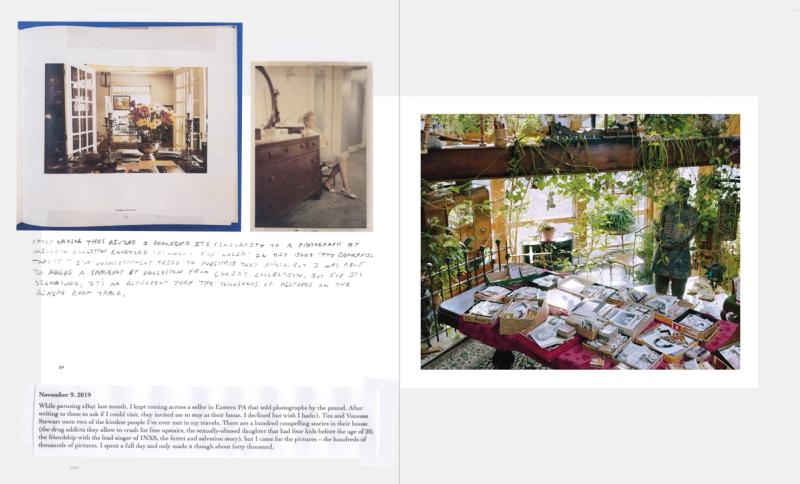

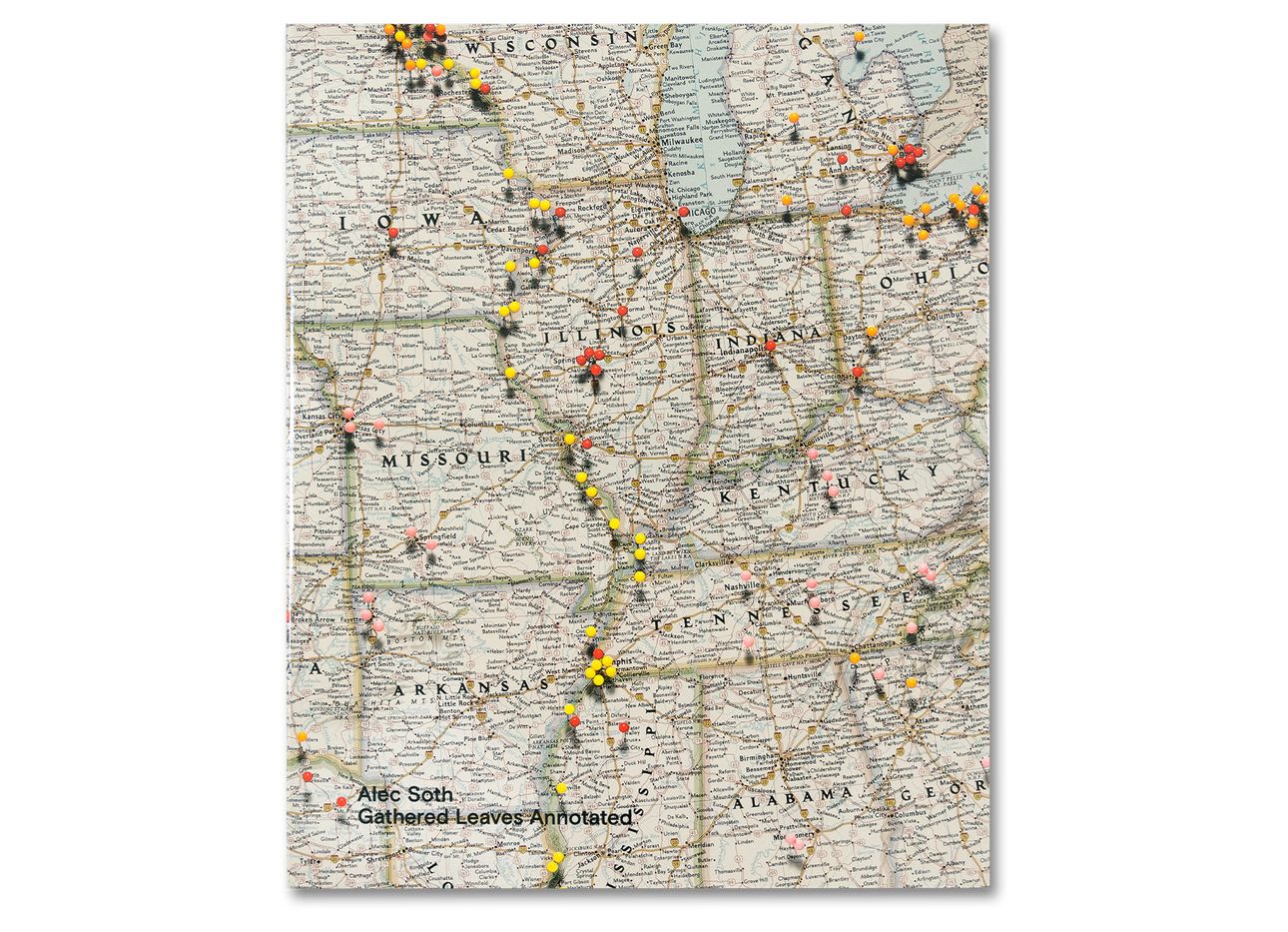

What does it mean to revisit a photograph? When a camera shutters, it locks a moment in time, forever trapping the image it renders. That well-trod notion, however universally understood, becomes unsteady in Gathered Leaves, the latest book by the Minneapolis-based photographer Alec Soth, whose work has long documented lonely souls and fractured dreams in spaces across the United States. In Gathered Leaves, Soth revisits five of his previous books, including in its pages new notes, annotations, text excerpts, and even photographs—melding his works into a distinct and retrospective road trip across his accomplished career.

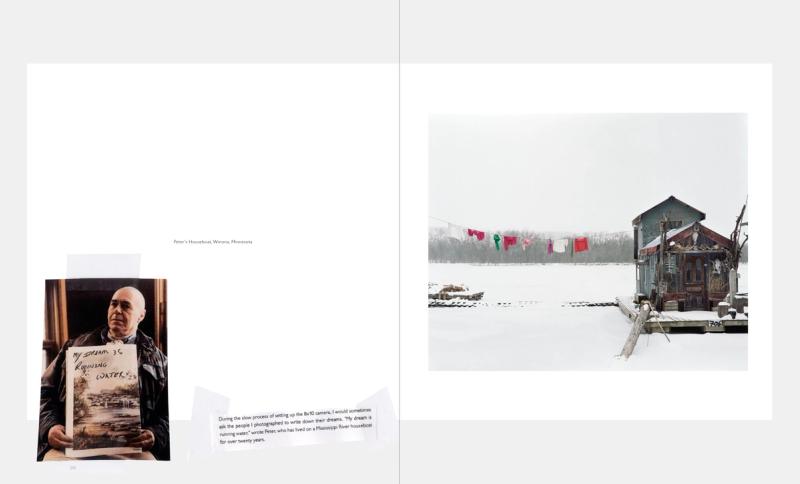

A sense of bleakness pervades parts of this project, echoing the pain and shattered hope in some of Soth’s earlier images. His annotations remind us of time gone by—in the years since publication, subjects have died, places or names have been forgotten, certain photos have become favored over others. In one image from Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), a thickly-muscled man named Lenny sits shirtless with his dog. A note on his table reads, “My dream is to live as long as I possibly can! I like to live to be 100 yrs old and look as I do now!!” Soth’s scrawled note reveals Lenny died in 2011, at age 54.

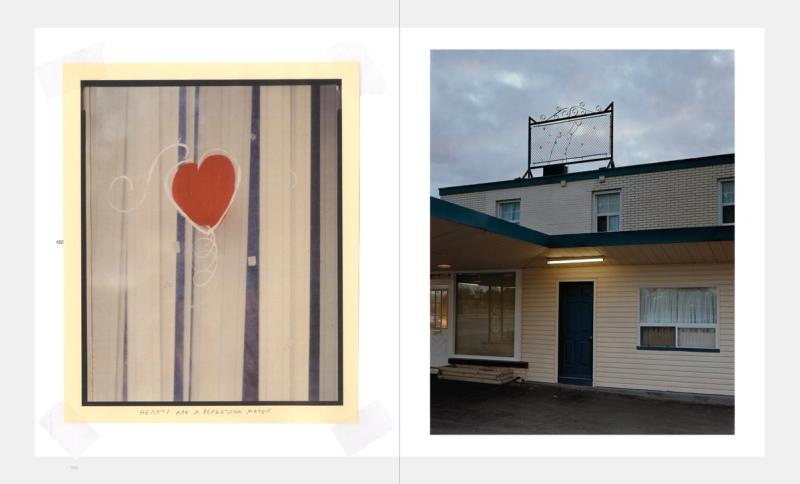

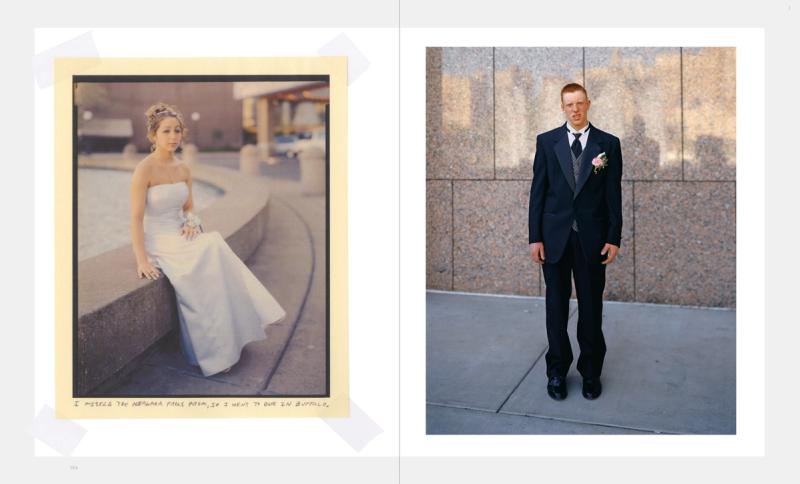

In a way, Gathered Leaves turns images, once captured and immortalized, into something fluid and contemporary. There’s an unstable temporality to the book, existing both now and then, imposing an alternation that is at times painful and sudden. All throughout, his photos capture visions of the Mississippi, Niagara Falls, hermits, and more. These are visceral, bleak, lonely, and haunting pictures. In revisiting Niagara (2006), for example, Soth admits that he could never quite portray love as clearly as the distance between partners. Flipping through the book’s pages can be a melancholy affair.

His new work takes us inside past journeys, with readers becoming companions in retrospect. As a reader and viewer, it’s as if you're sitting there with Soth over a beer, listening as he remarks and remembers these wayward memories. All the same, the new pages are snapshots, too, flies trapped in their own printed amber. Revisiting may update the past, but it serves only to freeze each moment in a new time. What this leaves us with is a sense of Soth’s immense depths of experience—that though we can view his book as something complete and enclosed, there are countless sights left still unseen.

Fans of Soth and newcomers to his work alike can find something deeply moving in this dense volume. The title of the book stems from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Like Whitman, Soth’s distinctive vision captures something new and timeless. As one flips through the volume’s pages—entranced by not only Soth’s images, but by his annotations, too—it is hard to think of Soth and his work as anything but poetry.