Dr. Gary Deng on Aligning Mind and Body Through Food, Traditional Medicine, and Self-Care

For nearly twenty years, integrative medicine specialist Dr. Gary Deng has guided patients through cancer treatment and recovery using a whole-body approach to health. Deng, who serves as the medical director at New York’s distinguished Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, aims to fortify his patients, inside and out. To do so, he has developed a methodology that combines current medical and scientific knowledge with evidence-based procedures from Eastern medicine, focused on issues including nutrition, exercise, and managing one’s circadian rhythms. Deng also counsels people on beneficial ways to incorporate herbs and dietary supplements into their diets, and works closely with a team of therapists who offer his patients acupuncture, yoga, massages, music therapy, exercise plans, and qigong, a centuries-old workout regimen that plays an important role in traditional Chinese medicine. Tailored to each individual, his distinctive approach promotes lasting physical and emotional healing.

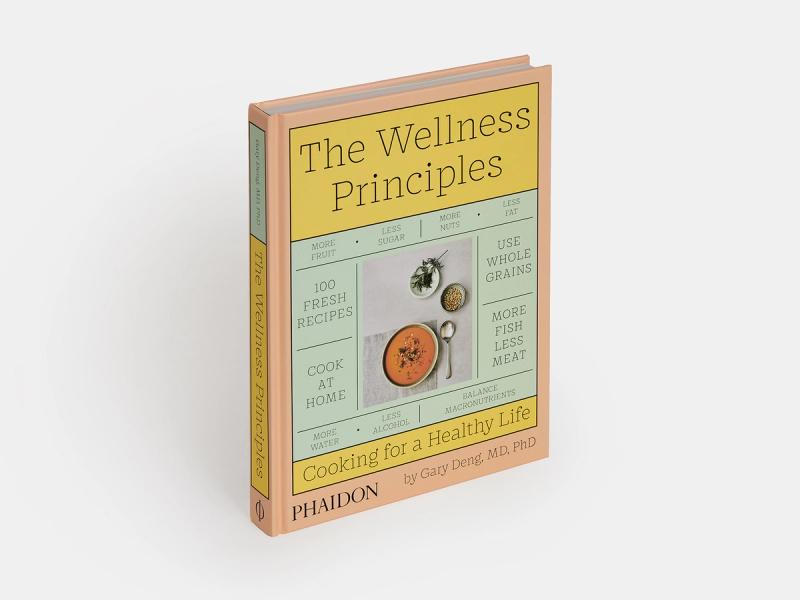

Outside of work, Deng practices what he prescribes. An experienced home cook who prepares three meals a day for his family, he just released his first cookbook, The Wellness Principles: Cooking for a Healthy Life (Phaidon), which features 100 of his efficient, accessible recipes. “I don’t have a lot of time, so I make it very quick,” Deng says. “Some of the dishes may take longer, but the hands-on time is very short: five minutes here, ten minutes there, and you’re done.” In addition to what to make and eat, the book offers plenty of food-related tips, including how to stock a pantry, how to add flavors to meals, and how to achieve a balanced lifestyle through practices beyond diet, such as stress management, getting enough sleep, and self-care.

We recently spoke with Deng about how food can contribute to wellness. He was careful to emphasize that healthy living isn’t only about diet. By focusing on specific parts of the body or individual treatments, he maintains, modern medicine often fails to consider health from a holistic perspective. He aims to do the latter.

How do you consider eating in relation to your work with cancer patients?

We see a cancer patient as a whole, rather than just a tumor. For that, we need to strengthen their body and their mind. Diet is actually one of the first questions people ask about when they’re diagnosed with cancer. My response is that this includes not only what you eat or don’t eat, but also how you eat. Take your time to eat, and pay attention to what you’re consuming and how that impacts you. There’s a mind-body connection to diet.

What you eat matters once it’s inside the body, too. A recent study found that a high-fiber diet helps the immune system fight cancer. It also cultivates a diverse, healthy gut microbiome that aids in digestion. We have hundreds of different species of microbes in our gut that interact with the body in very intimate ways. There are certain foods that we can’t digest without their help.

That kind of thinking can be useful to everyone. Are there specific foods you encourage people to make part of their daily intakes?

Some people think they need to go super healthy, like eating raw food exclusively, but that’s not very approachable. If a diet is healthy but not realistic, then it’s a moot point. Diversity in diet is more important than any single food, which can’t supply the many nutrients the body requires.

A nutritious diet doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy your favorite foods, though. In my cooking, and in my cookbook, I incorporate versions of common dishes that many people think are unhealthy. You can make pizza really healthy, for instance. It depends on what you’re putting on there, and how you cook it.

Right—you include instructions for how to make a delicious pie with low-salt whole-wheat crust and homemade sauce, and suggest toppings such as leeks, spinach, and cracked raw eggs. How does a lack of those kinds of food detract from overall wellness?

A lot of us don’t feel well. We feel tired, depressed, and have aches and pains all over. But when we go to the doctor and they do all the blood tests and scans, everything is normal. You’re not sick. But you’re still not satisfied with your state of being.

It’s like having a car that’s broken down, and having a car mechanic fix it so it can simply run again. Wellness takes things up a notch: it’s about fixing a car so it not only runs, but does so efficiently, and performs at the very highest level. Wellness is enjoying life to that degree, every day.

Integrative medicine ties into that. Can you elaborate on the role it plays in your work, and in contemporary medicine more broadly?

When I started out, there were very few medical centers that had integrative medicine programs. The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center was actually one of the first to establish one. Now, fifty to sixty percent of comprehensive cancer centers in the country have them. Some insurance companies, and even Medicare, have started covering acupuncture. There’s definitely an increasing acceptance of it, which stems mainly from research that has been done in the U.S.

Integrative medicine sees the human body as a whole, rather than parts. It incorporates a lot of practices from other medical traditions, such as traditional Chinese medicine, naturopathic medicine from Europe, or Ayurvedic medicine from India. But we don’t just blindly integrate East and West—we look at the scientific evidence. We incorporate ancient practices that have proven benefits.

And the approach views the mind and body as equally important components of a healthy person.

Exactly. I don’t understand the separation of mind and body, because we all know that humans have very well-developed minds. When you’re in pain, you’re not going to feel happy.

The reason we separate the two is because modern medicine was developed from a very reductionist viewpoint. It considers things as isolated parts, and zeroes in on the small pieces individually. When you’re focusing on that too much, you can lose sight of the bigger picture.