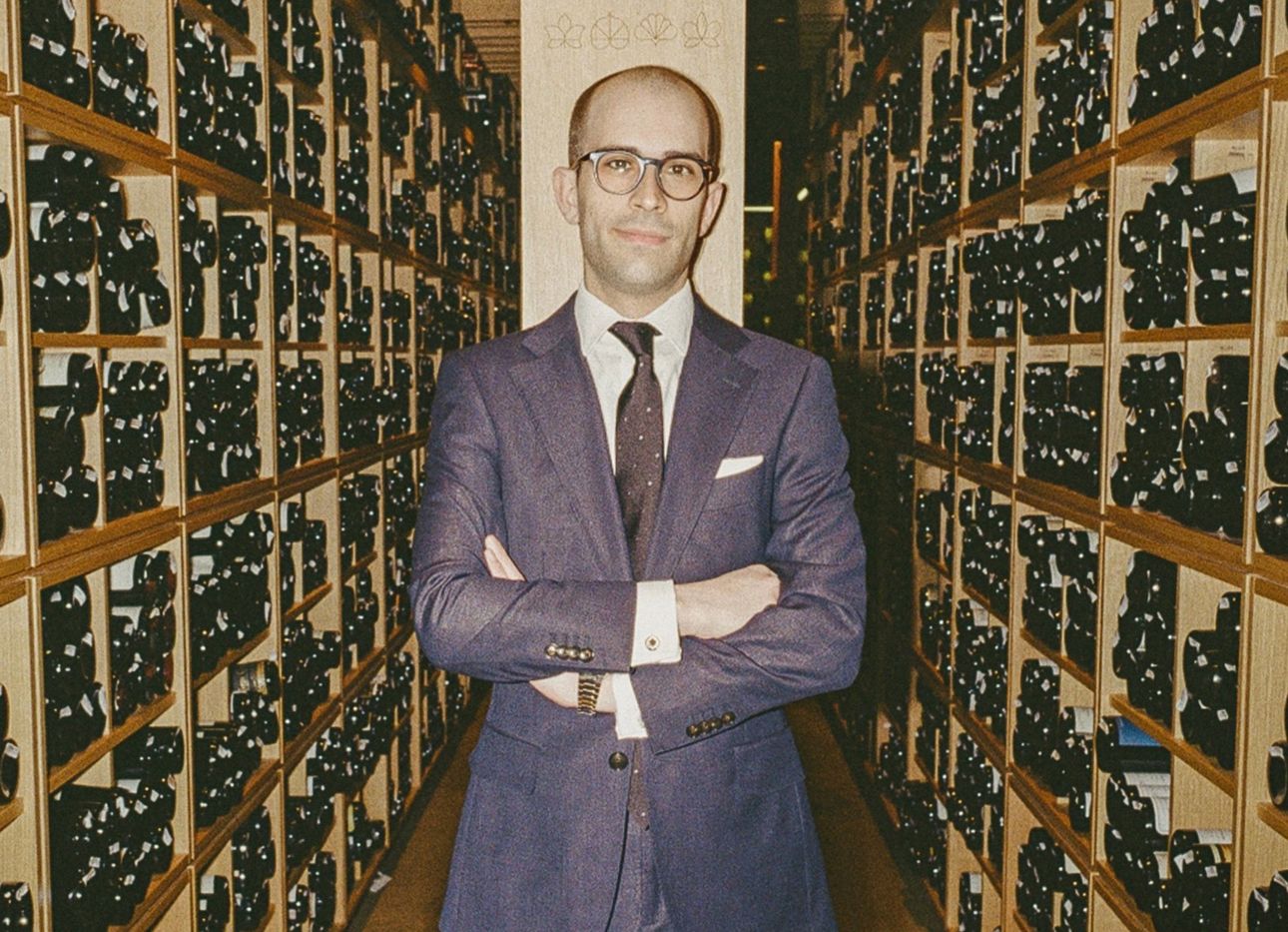

For Eleven Madison Park’s New Sommelier, Smell Is the Most Important Sense

Born into a Franco-Sicilian restaurateur family, Gabriel Di Bella traces his passion for food and wine to helping his chef father, Giuseppe, run their family operation in the French city of Vichy. After graduating from the distinguished Tain-l’Hermitage professional wine school in the Rhône Valley, Di Bella joined the team at Alain Ducasse in Monaco. Eventually, he made his way to London, where he worked his way up to head sommelier at Marcus Wareing, at the Berkeley Hotel, and then oversaw the wine programs for the restaurant group Caprice Holdings and the Birley Clubs, the latter of which includes the legendary lounge Annabel’s. In the summer of 2019, he joined chef Daniel Humm’s opening team at Davies and Brook, at Claridge’s London, as the wine director, a position he held until Humm and the hotel’s management parted ways at the end of last year, unable to agree on Humm’s new plant-based direction (“The future for me, and for this company, is plant-based,” Humm wrote of the decision on Instagram, “and this is the path we must take”).

Since landing in New York City and starting this spring as the wine director at Humm’s Eleven Madison Park flagship (which transitioned last year to an all-vegan menu), Di Bella has been overseeing its 200-plus-page, 5,000-selection wine list, with its highlights from Bordeaux, Burgundy, the Rhône, and Italy. Currently in the midst of his first weeks on the job, Di Bella readily spoke with us about his life’s work—through the lesser-discussed perspective of scent—and how he’s thinking about wine pairings for vegan dishes.

What role does scent play in the wine experience?

A major one. We think of the mouth and taste buds as the primary aspect of drinking wine or eating food, but I believe the nose is at least equally important. Once you look at whatever you’re going to eat or drink, the next sense you’re going to use is your nose. As soon as you bring it closer to your face, the smell comes through first, always before the taste. Smell is crucial to the wine experience. Just enjoying the smell can actually be extremely fulfilling, and very intense. That’s why you’ll see very geeky sommeliers like myself spending five to ten minutes just smelling a wine in the glass, to witness its evolution as it opens up and slowly reveals layers and complexity and different aromas emerging.

How does scent interact with the other senses in our appreciation of wine?

Tasting wine is one of the few activities in which we use all five senses. You’ll even use touch when feeling the liquid inside your mouth, and hearing comes into play, too, with the pop of the bottle. Removing any of these makes the wine experience immediately more challenging, as we do when tasting with blackened glasses—your brain can even become convinced a white is a red. Similarly, scent is a key part of the learning curve with wine. I would estimate that thirty to forty percent is lost if you could not smell each wine, especially when you consider there’s also a residual scent experienced in the back of the palate. As a wine buyer, my nose is absolutely vital every single day.

With wine, does a linear relationship exist between smell and taste?

Wine experts and even nonprofessional wine lovers will test a lot of wines in different years, or the same specific producer in plots or varieties, or cuvées. Through the years, one builds a database in your brain from these repeated encounters to gain an understanding of what a specific wine should taste like. When you encounter a wine, and start by smelling, your brain starts to connect the sensory dots. So you expect something from a specific vintage. Perhaps it was a warmer vintage, or it was colder or rainy and therefore more diluted. But then comes the unexpected. This is where wine is truly magical. You can study and learn, and smell and taste wine for your entire life, and I promise, with its unexpected variations, wine is going to keep surprising you.

Is our memory with wine triggered by smell or taste, or a combination of the two?

It’s the smell for me, one hundred percent. I put my nose to the glass, inhale the first breath, and feel completely transported to another time and place.

Can we learn to appreciate certain wines more through their scent?

There are definitely a few producers or grape varieties where this is true. I’m a huge lover of syrah wines from the Northern Rhône Valley; when you think of a producer like Jean-Michel Stéphan, the wine always surprises me. From the first smell, the wine seems a little shy. A little closed, even. The more time passes, the more the wine opens up in the glass or in a decanter, and you really have the full expression of this variety and producer. Every single time, whatever cuvée I taste from this producer, the scent alone provokes a similarly strong emotion of pleasant surprise.

I also have a significant memory of the first time I tasted la Romanée-Conti Grand Cru, one of those iconic “unicorns” of the wine world. I was an extreme novice back then, yet just smelling the wine—and I probably did this for at least five minutes—I understood what set this wine at the pinnacle of the wine world.

What about the impacts of the climate crisis? Can we smell them in the glass?

Yes, some wine growing regions are reviewing their grape varieties in response to warming climates and less water. Obviously, this impact arrives in the glass. Over the past several years, we’re seeing much higher levels of alcohol and sugar due to a consistently warmer climate.

Looking at what the new generation of winemakers are dealing with, especially in California, climate change presents a really big challenge. Not knowing if you’ll even have a harvest and how that will impact the coming year, due to frost or fire, that would be bad enough. But they face this uncertainty not only for the coming year, but for a year or two after.

I’ve only been in the United States for two months, but already I’m very interested in Racines Wines, an experimental collaboration between Justin Willett, from California’s Tyler Winery, and vignerons Étienne de Montille and Brian Sieve, of Burgundy, with Rodolphe Péters, from Champagne. They’re seeking to produce pinot noir and chardonnay in the Santa Rita Hills. Their wines tend more lean and are made with less alcohol and less acidity. It’s just one of the wine world’s responses to climate change.

How does Eleven Madison Park’s transition to an all-vegan menu affect your work?

This does not make my job more complicated. In fact, I think it makes my work more interesting. The old way was about pairing wines with foie gras, fresh lobster, and, of course, duck as the main course. That made wine choices pretty straightforward. Now there’s much more room for curiosity, research, and pairing development. For example, working on our summer menu, I’ve found so much more to play with and explore. The luxury we have is that because we’re changing what Eleven Madison Park is, we can take a fresh look at wine pairing and shine a light on underrepresented regions. This expands so many possibilities. Our diners also arrive more open-minded. They know they’re going to have amazing hospitality, and that the food is going to be delicious. That level of trust opens them up to trying new smells and flavors. I’m thinking of Austrian wine producers like Markus Altenburger and Claus Preisinger. They each make such delicious wines that are worth showing off and sharing. Both are very versatile, fruit friendly, very savory styles of red wine.

Our summer menu is especially green and fresh. The chefs are experimenting with acidity in the kitchen. Reflecting that in the glass keeps my work really interesting. It’s definitely something our diners will be able to smell.