Fanny Singer’s Ode to Her Legendary Mother, Chez Panisse’s Alice Waters

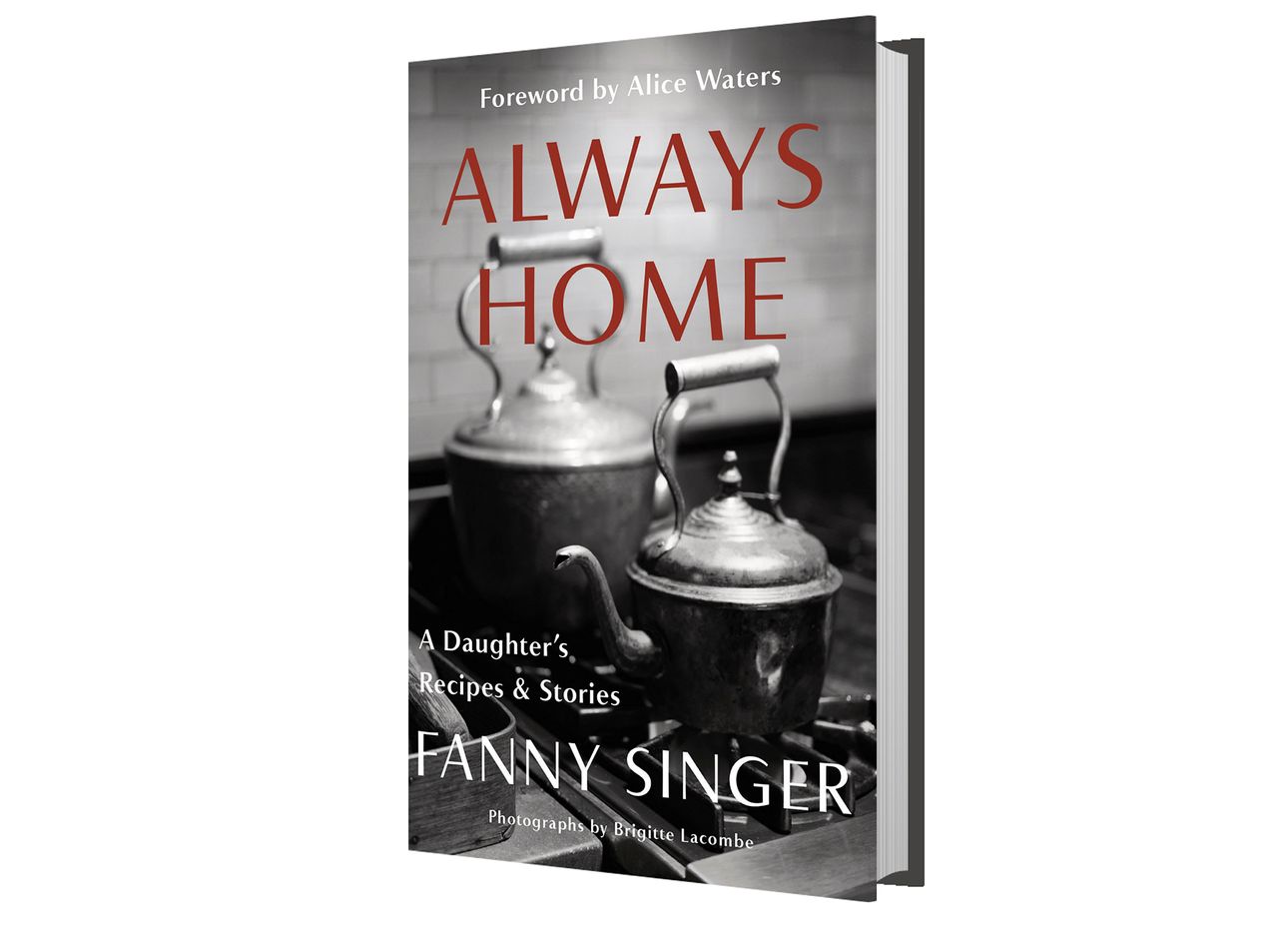

As the daughter of Slow Food pioneer and Chez Panisse founder Alice Waters, Fanny Singer has had her share of Proustian madeleine moments. Part memoir, part recipe book, her new book, Always Home: A Daughter’s Recipes and Stories (Alfred A. Knopf), offers a warm and sensorial portrait of her mother, and of an upbringing that often revolved around food. Here, she tells us about growing up with a food-famous mother, spending time abroad, and why she’s back in California for the long haul.

Always Home shares a lot of warm stories of your mother, and of growing up in the distinctive milieu of Berkeley and Chez Panisse, with a mix of stories, recipes, and photos. How did the idea for this book begin?

I think the reason it ended up taking on the form, at least partially, of a cookbook is that I was really thinking of my relationship to my mom largely in relationship to food, because we had collaborated on [the 2015 book] My Pantry, writing and working on recipes for that together, and the illustrations. I was imagining, well, what a book that I would write would look like? I thought, if it’s not an art history book, which is the other thing I might do, as someone who’s an art historian and an art critic, it would probably be tethered to food, and if it’s tethered to food, it has to have recipes.

I can’t really, authentically, just make it a recipe book because I’m not a professional cook. As I’m always saying, it’s a Frankensteinian thing! Part this, part that: part recipe book, part memoir, part love letter, and also part photo book—getting to work with Brigitte Lacombe on the images was a major coup. At the same time, that patchwork, that admixture and slightly strange format is what felt most authentic to me, and [informed] how I could write this type of book.

I love the story you share about the school lunches your mom would pack you: salads with different containers for each ingredient, only to be mixed before eaten. Were you aware, growing up, of your mom’s fame and particular approach to food?

I had truly insane lunches, and that wasn’t undesirable. I wasn’t a pariah, or ostracized for that or anything. My friends noticed that it was different, but also that it was better, that [those] things tasted really good.

I think moments like that made me aware [of my upbringing] at a young age, but I also loved certain junk foods as a kid, just because they were so exotic and different. I’d get things like strawberry Quik and burritos at my friend’s house, which I loved, because they were so unlike anything at my house. It wasn’t like I was a food snob, but I was conscious of a very different quality of attention to preparation and ingredients, because it was something that my mom was obviously completely obsessed by, and it was her professional imperative. She’s been this figure who’s been so present in so many aspects of my life, and my peripheral concerns, if not my primary academic ones, have always been around sustainability, good food, and cooking.

Her celebrity was something I was aware of from when I was pretty young, but her celebrity also increased exponentially just in the time that I was in England [for Ph.D. studies at the University of Cambridge]. It’s kind of a different kettle of fish now than when I was little.

As a writer, have you found that time away from home helped bring its contours into clearer focus?

When I applied to go to graduate school in England, I don’t think I imagined for a second that I would remain there for as long as I did. It just sort of ended up happening that way, as life does. When I first moved there, I felt too brash and bold for its eternally muted tones and reserved demeanor. But then I really found community through the arts world in London, full of artists and people who were also very extroverted and making things that were in public. That was a very different type of community than the academic one I was meeting initially, when I landed in Cambridge. In London, I felt really oriented and happy.

On the other end of things, as the title Always Home suggests, even when I was in England, I never did feel that remote. It gave me a protected distance from my mom’s reputation so that I was able to do things that felt truly autonomous, where people were not introducing me as “Alice Waters’s daughter,” or maybe didn’t even know who Alice Waters was, which was a gift in what was a fledgling period for me professionally, thinking, how can I create something or pursue things that are really uniquely my own, and that I’m achieving on my own merit?

Even writing this book, half of the attention I’ll get for it, or maybe more, will probably be because of association with my mom. Knowing that, how can I at least get the other half of the attention because the book is actually well written and well conceived? There’s always going to be that focus. It was sort of like, How can I make the most of it and also not prove anything to anyone, but maybe prove something to myself?

You’ve since returned to the Bay Area. How does it feel to be back home?

I’ve been back for two and a half years, and it’s been really great. I didn’t know how I’d feel when I came back, if I would feel phobic or like I had really found a place for myself. I feel the latter, mainly.

The other thing that’s been really important to me has been working to promote different arts organizations in the Bay Area that I think are really worthy, and which were virtually invisible to me when I was abroad. San Francisco is a much smaller place—about a tenth the size of London—but there just weren’t that many people here writing about it or covering it. So to be able to bring some attention and more international visibility to it has been really meaningful. It’s been good on many fronts. You know, when you’re far away from a parent you love, you’re able to rationalize it. But when you’re near and aware of the fact they’re aging and not going to be around forever—it almost seems now unfathomable that I would move much further away than life within California.