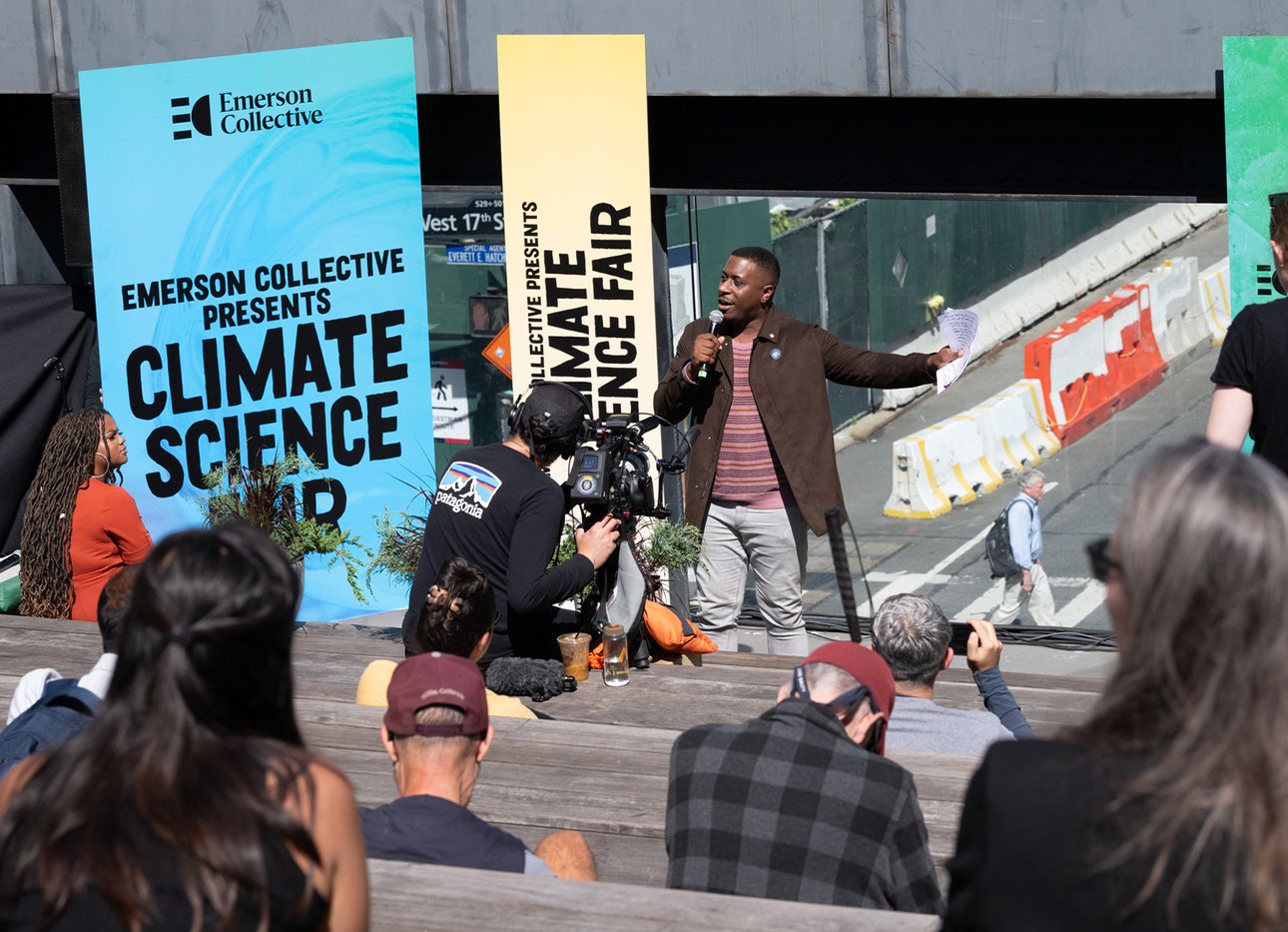

At New York’s Climate Week, a “Climate Science Fair” Cultivates Optimism and Future-Forward Thinking

This past Wednesday, I made a visit to Chelsea’s High Line, where a certain kind of science fair—coinciding with New York City Climate Week—is taking place through tomorrow, September 23: the inaugural Climate Science Fair, hosted by Emerson Collective in collaboration with the climate-tech nonprofit Elemental Excelerator. With the aim of cultivating climate optimism and impactful conversations about our collective future, the community-driven event features a keynote speech by the scientist and TV personality Bill Nye as well as presentations, performances, workshops, talks, soundscapes, and demos with a wide swath of leaders and innovators across sustainable agriculture, clean energy, textile recycling, and more, from Ghetto Gastro co-founder Jon Gray (the guest on Ep. 2 of our Time Sensitive podcast) to the marine biologist Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. “The heart of so much of our work is really thinking of the power of human ingenuity,” says Jennifer Arcenaux, senior director of Emerson Collective’s Culture Council, when asked about the impetus for the fair. “We thought the framing of a science fair—which is so accessible to all of us; we all know what it feels like to present, and the nervousness and excitement and all of the creativity that went into designing our own demos in grade school and middle school and high school—was a beautiful way to capture and translate these ideas in a way that’s truly accessible.”

What it may lack in volcanic paper-mache eruptions, vegetable batteries, or any kind of goo, the Climate Science Fair makes up for in ingenuity, diversity, big questions, and, often, equally big answers. Featured among the nearly two dozen organizations present at the fair—each placed according to the categories “Solutions at Scale,” “Farms Fixing Food,” “Collective Creativity,” and “Nature”—is an organization planting millions of climate-resilient trees, a company creating the world’s first hybrid-electric airplane, and an entrepreneur converting textile waste into regenerative fiber.

Wednesday, breezy and blue-skied for the opening day, saw a buzzing crowd weaving their way through the event, which spans the 14th to 17th Street stretch of the High Line. Arriving at the 10th Ave. Square venue at the north end of the fair, I sat down for a talk between the landscape designer, urbanist, and public artist Sara Zewde of Studio Zewde and Emerson Collective’s managing director, Dan Tangherlini, on designing for sustainability. The question they started with was: “How is your community changing, and how do you want it to change?” The responses from three audience members, who hailed, respectively, from Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Portland, Oregon, were strikingly aligned, centering around bike safety, affordable housing, and increased public infrastructure such as parks. “Parks are the lifeline of a city,” Zewde said. “They’re not only carbon sinks, helping to provide clean air for the city, but are also intrinsically democratic. They allow everyone to have outside space to walk, exercise, or just be.” This remark put into perspective the very public park in which we all sat—its vital role in Manhattan’s landscape and how much life it and other parks add to the city.

Following the talk, I meandered south toward the Chelsea Market passage between 15th and 16th Street to find the “Farms Fixing Food” stands. The first was Sky High Farm, a nonprofit organization committed to addressing food security, whose presentation, at first, appeared to be a big pile of dirt. As I soon learned from Lexie Smith, Sky High Farm’s program manager (whom I got to know while volunteering at the farm earlier this summer), the mound, made up of soil sourced upstate, contained a number of seed packets for visitors to scavenge by reaching their hand in and feeling around. While I dug my hand in, I learned more from Smith about how Sky High’s operation fits into the climate conversation. “Our project is about people, first and foremost. You can’t have a healthy planet without healthy people, and you can’t have healthy people without a healthy planet,” Smith told me. “Our interest is in creating sustainable systems within communities that allow them to grow food in a way that is kind to the planet, to their bodies, and to their communities as well.” (Sky High’s founder, the artist Dan Colen, was the guest on Ep. 40 of our Time Sensitive podcast.)

Next, I passed by Project Eats, an organization transforming vacant lots and rooftops into neighborhood-based farms in order to cultivate greater food sovereignty across New York City, who are partnering with the Chelsea-based community agency Hudson Guild for the fair. The organization is the only one that’s set up at two locations on the High Line, one at 15th Street and 10th, the other at 26th Street and 10th. Project Eats’s founder, the filmmaker and activist Linda Goode Bryant, said, “There are two sides to this avenue: east and west. Many of the folks that live on the east side of Chelsea are people who are living in public housing. Many of the folks that live on the west side of Chelsea are people who live in very expensive housing. There are invisible barriers that make it so that the people who are living in public housing don’t come to the High Line. So [I thought], why don’t we set up at those two locations, and really see who these two communities are—where they align, and where they don’t?”

As a whole, the Climate Science Fair serves as a rare opportunity for an optimistic, forward-looking, generative, in-person meeting of minds not just between creatives, thinkers, and innovators spearheading the sustainability movement, but also with the members of the public they’re working to support and sustain. Perhaps above anything else, the experience prods visitors to take on a wider, more intersectional interpretation of that much-overused word—sustain—underscoring the mutual importance of doing so for both the communities we belong to and the planet we share.