Elyn Zimmerman Created a Memorial to the 1993 World Trade Center Bombing—Then It Was Destroyed on 9/11

Elyn Zimmerman will never forget the exact moment when, on February 26, 1993, a truck bomb exploded in the World Trade Center’s underground parking garage, killing six people and injuring more than a thousand. The artist and sculptor’s studio at the time was in Tribeca, just off Varick Street, and when the bomb went off, it was felt, both literally and figuratively, across downtown New York City. It would become a traumatic precursor to the even more harrowing events to come, less than a decade later, on September 11, 2001.

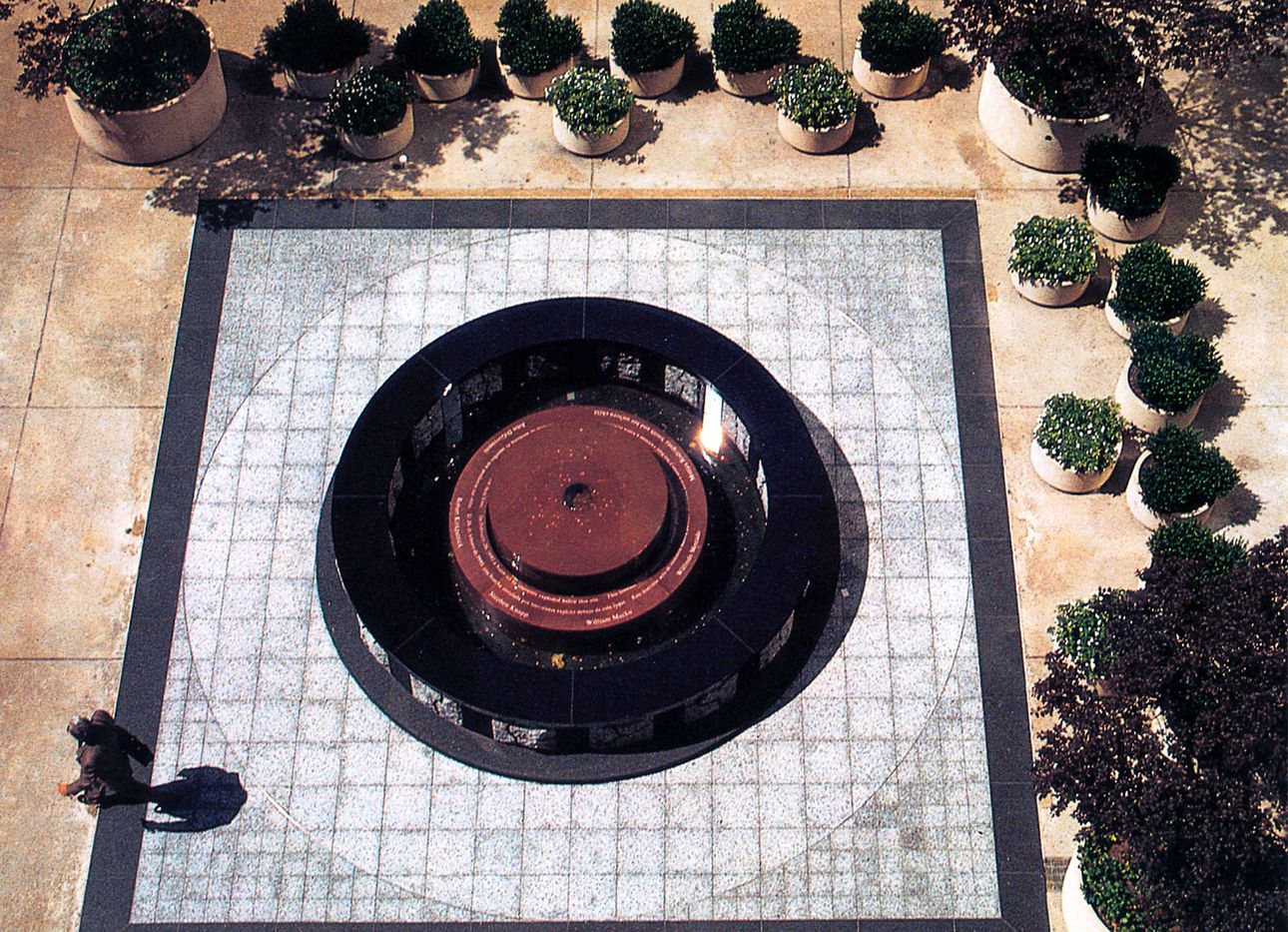

In March 1993, following the bombing, the Port Authority of New York created a temporary memorial, then issued a competition to design a permanent one. Zimmerman applied and, out of more than 2,000 entries, won. Her concept was completed just two years later. A circular, 30-by-30-foot granite fountain placed in a central plaza between the two towers, the memorial was inspired, in part, by the ancient sanctuary of Delphi in Greece, as well as by tumulus burial mounds. Offering a humble tribute to the victims, the minimalist disc-shaped work was inscribed with each of their names: John DiGiovanni, Robert Kirkpatrick, Stephen Knapp, William Macko, Wilfredo Mercado, and Monica Rodriguez Smith (and her unborn child). It was also inscribed with text that read, “On February 26, 1993, a bomb set by terrorists exploded below this site. This horrible act of violence killed innocent people, injured thousands, and made victims of us all.” A Spanish translation, the native language of two of those killed, was featured as well.

Then, on 9/11, as the towers fell, the memorial was destroyed, crushed into the rubble. Only a single fragment, with just the inscription “John D”—the beginning of DiGiovanni’s name—was recovered. (The letters “mem,” from “memoria” in the original inscription “Esta fuente está dedicada en memoria de aquéllos que perdieron sus vidas,” also appear at the top of the fragment.) In 2005, that small remnant was placed in a temporary memorial, and has since been moved to the 9/11 Memorial Museum, where it’s presented among thousands of artifacts from the 1993 bombing and the 9/11 attacks. Here, Zimmerman discusses the making of her memorial and its journey to becoming a memorial within yet another memorial.

“Are you aware that the Port Authority has an art program? Saul Wenegrat was in charge of it for many years, and [the group] chose works for the plaza at the World Trade Center, and also for other Port Authority locations. They ran this [memorial] competition, and went out of their way to invite artists who had done sculptures in public places. The area [for the memorial] was limited to the plaza directly above where the incident happened, which was between the two corners of the two towers. And this was done purposely, because the [terrorists] setting the bomb thought that that would cause the towers to collapse into each other.

If you know anything about my work, I’m inspired by archeological sites and ancient ruins. I collect books on architecture, and there was a book [I referenced] about historical memorials that go way back in time and the history of cemeteries. That’s where I started looking: all the way back, as far as I could. For the form of it, I thought of what the tombs were in ancient Greece, in Rome. It had a particular vocabulary. I wanted it to be as sober as possible: white granite panels, very rough, hand-chiseled; black granite uprights going around in a circle.

The thing about it being a memorial was the contact I had with the families, and seeing how much it meant to them. This terrible thing had happened in my city. Given that there was a limited amount of funding, I just wanted to do something that was dignified and brought people together. What was amazing to me was that the families who I got to know and talk to considered this their monument to their lost family members. They visited every year. I don’t know if they communicated with each other, but every year, on the anniversary of the event, members of the various families would come. They’d bring flowers. They’d pray.

On 9/11, I heard the [American Airlines Flight 11] airplane come over my loft, because I live in SoHo. My husband did, too. We heard people running out into the streets. My mother called, thinking that we should leave our loft, because the tower is going to collapse and crush all of the buildings—she lives in Florida, so you can excuse her. But we ran out and, standing at West Broadway and Prince Street, saw the second plane [United Airlines Flight 175] go into the South Tower. Honestly, at that moment, we didn’t know how many people had survived—or didn’t survive. We just thought the world was coming to an end. It was pretty grim. About an hour after the buildings collapsed, all of a sudden, a squadron of fighter jets came flying over the city doing loop-de-loops ... two hours too late. Where had they been earlier?

[During the course of the site’s clean-up] an officer at the Port Authority, in their New Jersey building just across the Holland Tunnel, called me and said, ‘We’ve found something. We think you’d be interested in seeing it.’ They had it in a beautiful wood box, lined in velvet. It was as if this was, to the Port Authority—and to the families [who lost relatives in the 1993 bombing], of course—some sort of sacred piece. That made me cry more than anything else. I didn’t think of anything except that these poor families [who] had lost people once, now losing the memory of them again.

I think what distinguishes the memorial I made [from the one at the World Trade Center site now]—is that it was very personal. It was small. After 9/11, the site became so corporate and so wrapped up in money and [Larry] Silverstein, and who pays for what, and the insurance. I mean, it was just gruesome. It lost its humanity. In my mind, it’s not that there weren’t talented people involved—there were, and there are. And I have visited the [“Reflecting Absence”] plaza and the museum, and I think they’re great. It came out better than I thought it would. But the scale is just so big. It’s very different. So this much smaller thing got wrapped up into a much larger situation.”