David Byrne’s Drawings Reflect on the Absurdities of Life That Connect Us All

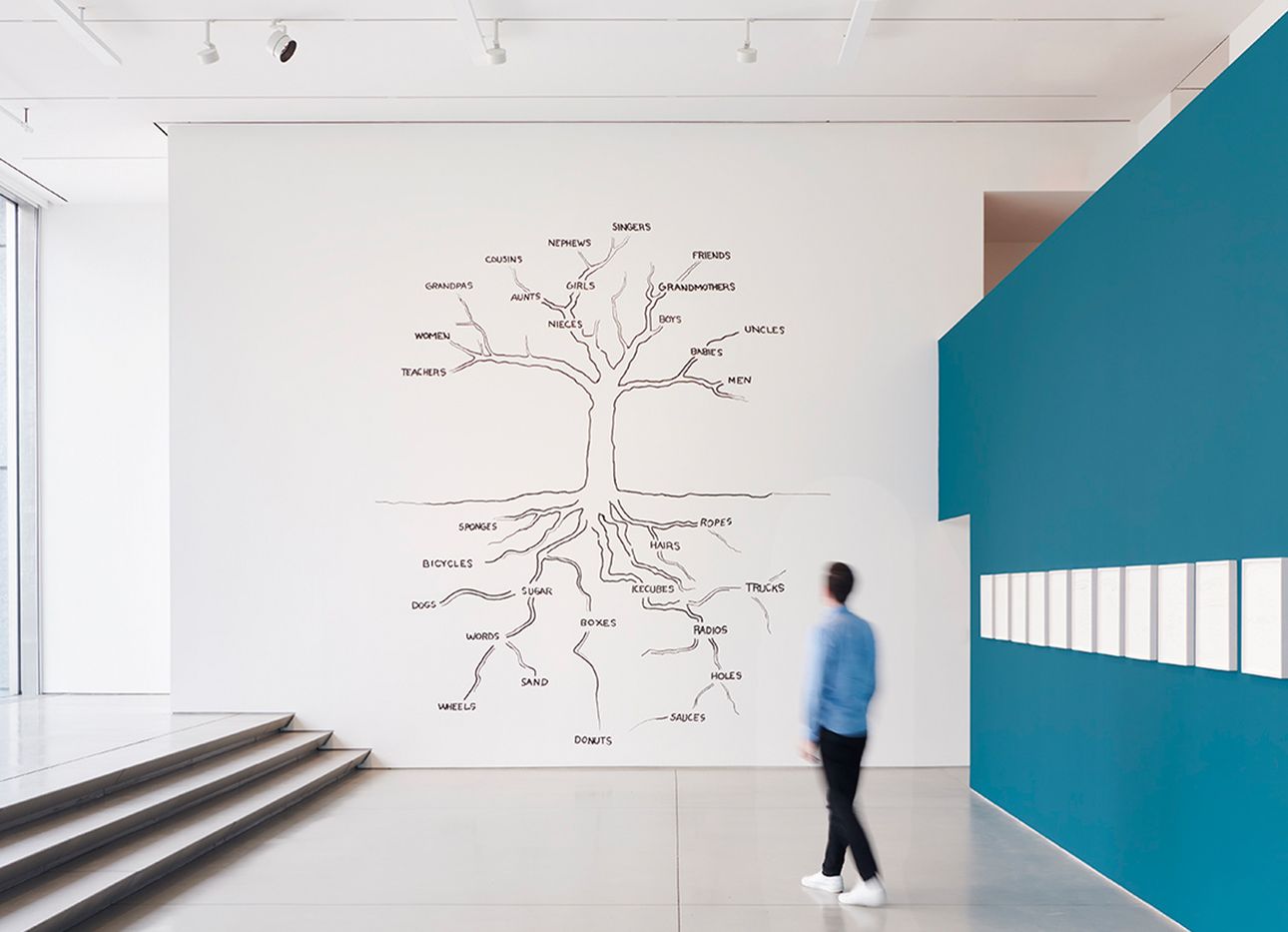

Thick, wobbly lines branch out across a wall of Pace Gallery’s global headquarters in New York. Follow each stroke to its end, and you’ll find words like women, grandpas, and singers craning toward the ceiling, and donuts, hairs, and holes reaching into the ground. Part absurdist diagram, part heart-melting poem, and part consciousness-shifting artwork, this big tree acts as a delightfully uncategorizable introduction to “David Byrne: How I Learned About Non-Rational Logic” (on view Feb. 2–March 19), a restorative survey of drawings the musician has made over the past two decades.

The show gathers a selection of works from three groups of Byrne’s drawings: tree diagrams from the early 2000s, chairs from 2004–07, and dingbats, a series of amusing, somewhat surrealistic interpretations of everyday life he’s been making since the pandemic began. The latter, which riffs on the typographic symbols used to break up or replace text, also features in the book of A History of the World (in Dingbats) (Phaidon), out in March, alongside Byrne’s poetic, philosophy-inflected writings on shared human experiences.

Like the lyrics Byrne famously spun for the body-shaking anthems of the Talking Heads, the rock band he performed in as the lead singer and guitarist (and whose songs he performs in the current Broadway show American Utopia), his drawings pare down and synthesize everyday elements into unexpected, iconic forms. At their best, they subvert logic to help us see the world in new ways; when that doesn’t happen, they will likely induce a sudden, much-needed laugh.

Beyond the mural that fills the exhibition’s opening wall, other pieces are intimately scaled, clocking in at around the size of a standard sheet of paper. Viewing them up close reveals deft, hand-drawn ink illustrations, including the existential, deeply funny “Who’s a Pretty Boy Then” (2021), which depicts a pigeon gazing into a mirror while a reflection of a shocked man stares back; and “Miniaturization Is the Future!” (2021), in which a giant finger attempts to maneuver a Lilliputian phone—a big-tech–skewering fool’s errand. Their playfulness and size belie their strength; each drawing taps powerfully into the collective consciousness.

“Humor sometimes allows us to say the unspeakable. To diffuse the nightmare and yet still somehow view it face on,” Byrne said in a statement about his dingbats diagrams. He views them, he continued, “as being somewhat hopeful—the rise of the collective is what might save us.” His words—and all of Byrne’s drawings, for that matter—hark back to that tree that opens the show. It’s titled “Human Content,” a playful dissection of what people are made of—the stuff that roots us and draws us together.