A Liberating, Time-Traveling Journey Through Family, History, and Memory

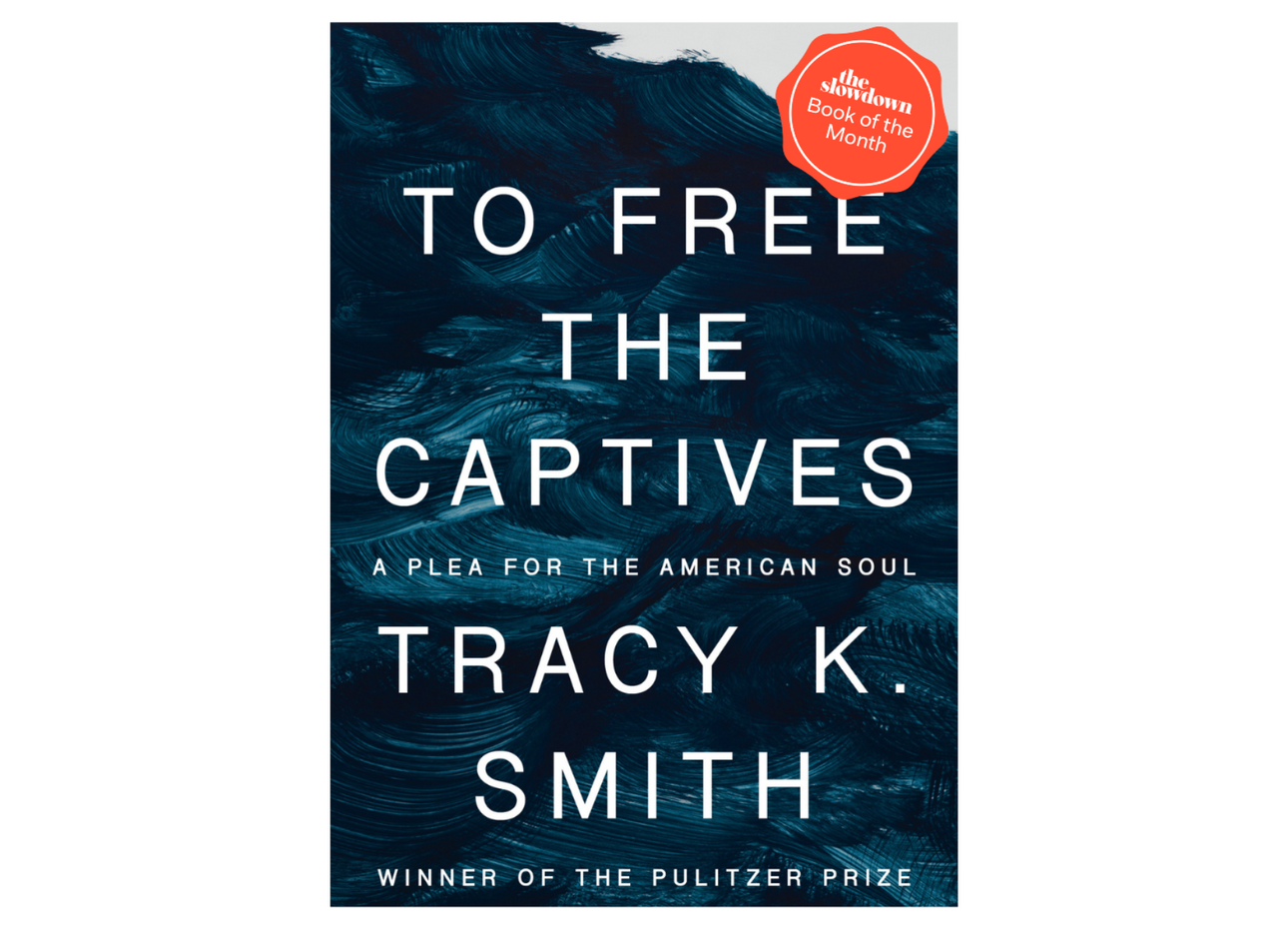

Family. Memory. Legacy. These words, these themes, build upon each other. Within our families there are shared moments, sometimes of joy, sometimes of pain, that help write our stories. These stories, passed down as lore, or as photographs, become memories. And with time, as memories stretch and years pass, legacy is created. In her latest book, To Free the Captives: A Plea for the American Soul (Knopf), the former U.S. poet laureate Tracy K. Smith examines the deepest of American wounds through her own family. This searing memoir travels through time, relationships, and Smith’s own life to illuminate the lasting legacy of racism in our country.

Smith is the acclaimed author of five poetry collections, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 2011 for Life on Mars. (It’s worth mentioning here that, from 2018 to 2020, she was the host of the poetry podcast The Slowdown, which has no relation to the media company publishing this article, though both, by coincidence, were launched around the same time.) She has tapped into her family’s history in her previous works, notably in Life on Mars, which pays homage to her father’s life and work as an engineer on the Hubble Space Telescope, and in her first memoir, Ordinary Light, a book about her childhood, her close relationship with her mother, and her mother’s illness and death. It is profound and touching to see Smith so sensitively explore her connections to her mother and father within her work, and to connect her relationships with them to how she moves about the world.

To Free the Captives arose out of the grief Smith felt in the wake of the events of 2020: witnessing attacks on Black life and experiencing a nation undergoing a collective reckoning about racism. Smith writes that she weathered the pandemic in the safety of her New Jersey home, but calls that sense of safety false, knowing, and having witnessed, that at any moment, life could be taken from her. Watching Black death and the reactions to it—and even, at times, justifications for it—weighed on her.

Smith opens To Free the Captives with her grandfather on her father’s side, placing us in Sunflower, Alabama. After returning home from serving his country in World War I, he is still treated as a second-class citizen, denied securities and opportunities promised to servicemen—much like how the promises of Reconstruction failed to materialize after the Civil War, paving the way for decades of inequality and a constant fight to reclaim what was owed. Despite these failures, or maybe in the face of them, her family’s strength endured. This theme of resilience—the idea of surviving in the face of struggle—loops throughout the book.

Shying away from narrative, but managing to keep an eye on the stops along her journey, Smith manages to thread lyrics and anecdotes into her work as she critiques history, lives through current events, and reflects on how we can move forward. In a recent WNYC interview with Brian Lehrer, Smith comments that “one of the big concepts that the book seeks to explore is the nature of freedom as it exists in the American imagination.” She goes on to explain that she’s come to see freedom, through the eyes of our culture, as something “belonging differently to different people. People that I describe in the book as free are those who appear to descend from histories of power or ownership.” The freed, the captives, therefore appear to be less deserving of freedom than those who were always free and had the power to make these classifications.

The work of what she terms the “American imagination” is clearly visualized in two encounters within the book. The first is when Smith pays a visit to “the oldest plantation in Georgia remaining with its original family” while working on an opera libretto. She has trouble reckoning with how the plantation is described as “remaining with its original family,” her mind instantly considering the enslaved people who also lived and worked there. This conflicted feeling only grows stronger as Smith and other guests share a meal. “It is a labor to keep my thoughts from where they wish to go,” she writes. Later, in her bedchambers, Smith has an imagined conversation with a young Black woman—a ghost?—and finally voices her feelings. That the family can skim over the violent history of their land (land that was stolen, as Smith notes) shows her that they have not considered what it meant to live a life in the shadows of their great home, to be the backbone upon which it was built and survived.

The second encounter is Smith’s meditation on her first marriage, to an artist named Diego, whom she met in Mexico. In their neighborhood back in the States, she describes how he was stiff around their Black neighbors and other members of their community. He commented that he didn’t consider his wife to be “one of them”—in his American imagination, Smith was beyond racial stereotype and discrimination, solely because he had taken the time to know and love her. And yet, he did not extend that thinking to other Black Americans because it allowed him to be above them. I appreciate Smith’s vulnerability in sharing these reflections. In doing so, she demonstrates how we can be complicit in our ignorance.

To use one’s own family and one’s own life experience as a way to map the legacy of slavery and racism in this country is beyond powerful—it’s an act of reclamation. To know that there are stories among uncles and cousins, the lives of our grandparents, and the ones who came before us, and to think of how they shape the lives we lead brings Smith’s work home. As noted by the subtitle, the work is indeed “a plea for the American soul,” a personal understanding of what the past can teach us and how we learn from it, if we choose to. As Smith writes, “The scale of Black hope has never been content with a single person’s freedom, or even a single people’s freedom. Rather it is grounded in the wisdom that genuine freedom brings with it the transformation—the true liberation—of all humankind.”