Desiring Beauty, Even If It Kills Us

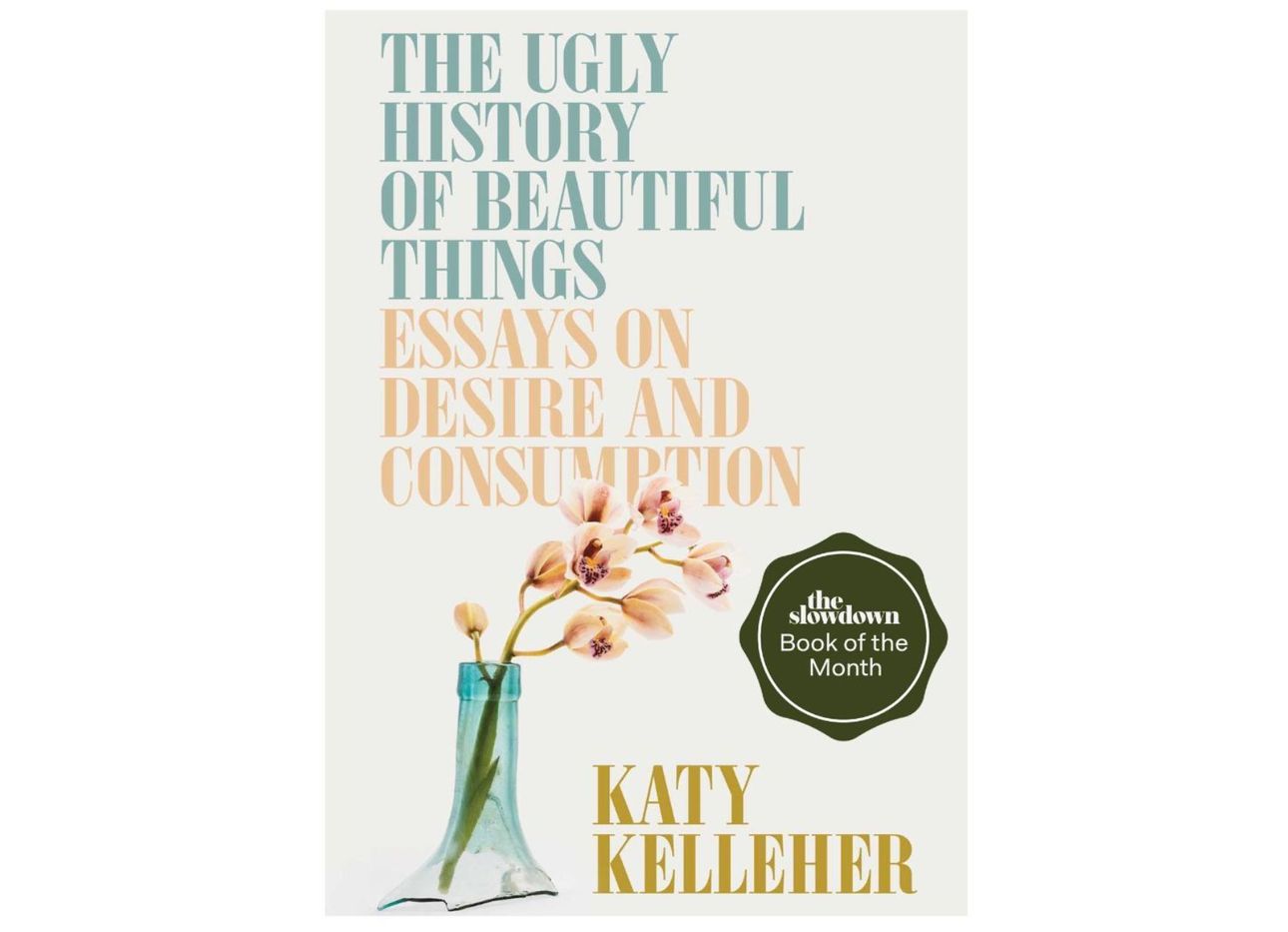

As I was reading Katy Kelleher’s beautifully written new book, The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and Consumption (Simon & Schuster), I found myself returning to a conversation I once had with the graphic designer Stefan Sagmeister, who in 2018 himself published an astute book on beauty. “If you’re in an environment that is lacking beauty,” Sagmeister told me, “you are becoming an asshole.” Cheeky as his comment may have been, he has a point. But beauty is also much more complicated and contradictory than that. As Kelleher’s book makes all too clear, the beauty that surrounds us is important and, in many cases, essential, but there’s also a lot of ugliness hidden in its making and in its wake.

Both a celebration of and ode to beauty, Kelleher’s book is also a glaring, blaring acknowledgement of its attendant sinister sides—in other words, the ugly. Exploring the space between the awe that beauty brings and the havoc—cultural, social, moral, political, environmental—that beauty can wreak, The Ugly History of Beautiful Things spans a wide variety of subjects: mirrors, flowers, gemstones, seashells, cosmetics, perfume, clothing, glass, porcelain, and marble, in that order. Combining memoir-ish first-person accounts with historical research, it is a roving and riveting romp through the material world. Kelleher illuminates deep, dark truths not only about the objects and artifacts she unpacks, but also about who we are as human beings.

Kelleher’s particular lens on beauty makes for some entertaining, if heart-wrenching and cringe-inducing, reading. When writing about Venetian mirrors, which were “considered the height of luxury” in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, she highlights the many ailments suffered by the mirror-makers who produced them and goes on to tell a horrific tale of violence and murder. “Mirror-based cruelty,” she calls it, a phrase that could fittingly apply to our contemporary moment and “the slow, quiet suffering caused by our cultural obsession with looks.” Never stuck in the past but still rooted in it, Kelleher’s storytelling consistently pulls readers back into our present—in this case, to our social media age, with its flattening and condensing of our public and private selves. “Perhaps that’s the ugliest thing about mirrors,” she writes. “They reveal more about society than they do about individuals.” From one well-crafted sentence to another, Kelleher skillfully makes the case for mirrors being synonymous with cruelty.

At her best, Kelleher opens up new ways of thinking about subjects that may seem obvious but that are surprisingly underexplored. In her essay on glass, which she calls “perhaps the most frequently overlooked material in history” (and, as she proves, this statement holds up), she takes readers from the origins of the material, to the development of stained-glass windows, to eyeglass lenses, to the light bulb, to vaccine vials, to the creation of the smartphone. “Humans love a spectacle,” she writes. “Out of the players in the material world, I think glass is the ultimate trickster. Although glass can illuminate rooms and lives, it can also distort reality and obscure the truth…. Glass sharpens our vision but not necessarily our understanding.” Our everyday reality is, Kelleher points out, literally formed and made by this single material.

Similarly, her essay on gemstones—and particularly the section on diamonds, “the ultimate consumer symbol of commitment in American culture,” as she puts it—is as expertly polished and cut as the very rocks of which she writes. Though Kelleher tells the widely known story of the mining magnate Cecil John Rhodes (1853–1902) and his formation of De Beers, as well as the creation of the company’s now iconic “A Diamond Is Forever” campaign, she manages to keep her prose pristine and highly engaging. This is in part because the essay is about much more than De Beers: She also effectively illustrates “the mysteries of the human brain and body” (her words) and the dynamic relationship between hope and beauty. “As a species, we’re marvelously skilled at inciting desire,” she writes, sounding a bit like historian Yuval Noah Harari on one of his philosophical jaunts about humanity’s evolution.

Kelleher’s first collection of writing and only her second book—following Handcrafted Maine, which profiles more than 20 artists and makers in her home state—The Ugly History of Beautiful Things cements Kelleher as an essential American essayist, someone following in the wandering footsteps of feminist-naturalist writers such as Diane Ackerman and Rebecca Solnit. Reading “Dirty, Sweet, Floral, Foul,” Kelleher’s essay on perfume, I found myself thinking of Ackerman’s A Natural History of the Senses, which soon enough I came to see Kelleher aptly reference—only Kelleher goes much further, down into the murky depths of fragrance production, making potent links between perfume and the HIV/AIDS epidemic, cancer, and racism. In her essay “Women and Worms,” about the gluttonous waste of the fashion industry, Kelleher’s writing evokes the hopeful tone of Solnit when she describes the history of silk as “a story about people: goddesses, peasant women, concubines, wives, daughters, bridges, babies, and slaves. It’s a story about economics, certainly. Yet tangled within these tales of public exchange, there’s also flashes of intimacy, glimmers of resistance, and a sturdy sense of hope that accompanies the radical act of mending.”

Admittedly, some of the terrain that the book explores is already well-trodden. Having previously read Edmund de Waal’s The White Road, for example, I found her essay on porcelain fairly predictable and not particularly eye-opening. And in one case, I found myself completely disagreeing with her take on Frank Lloyd Wright’s design of the Guggenheim, which she calls “the elevator-music version of a seashell.” Ouch. But she doesn’t stop there. “Frank Lloyd Wright applied order too thickly, color too thinly, and texture too sparingly. A string of man-made pearls has the same pristine luster, the same blindingly white conformity.” Oof. “Like the porcelain teeth of a Hollywood might-be, the Guggenheim’s architecture has always struck me as an empty triumph of human will.” Yikes. Beauty is, of course, subjective and highly personal, but to call the Guggenheim, which remains one of the most extraordinary—and, to my eyes, beautiful and astounding—examples of modern architecture, “an empty triumph of human will” seems a stretch. In her essay on fashion, when trying to highlight issues of child labor, Kelleher sources some decidedly dated references—a 1996 report, 1997 textbook, a 2003 Human Rights Watch report—resulting in a weak, if no doubt still valid, argument.

No matter. These are just a few nitpicks. Kelleher’s book is an absolute triumph and a testament to the persistence of beauty in our culture, in our society, and in our minds. This is a book that I’ll be processing for a long time to come. I will never look at a beautiful object the same way ever again.