With “Open Questions,” Helen Molesworth Opens Up New Ways of Seeing Art

I find essay collections captivating because they offer the opportunity to dive in at any point. Of course, reading them in chronological order is the typical method, but sometimes a topic or a theme calls out to you. In reading Open Questions: Thirty Years of Writing About Art (Phaidon) by Helen Molesworth, the first-ever collection of her art writing, I did in fact start from the beginning.

To backtrack slightly, Molesworth is a Los Angeles–based writer, curator, and host of Dialogues, a podcast produced by David Zwirner gallery. From 2014 to 2018, she was the chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles and, prior to that, from 2010 to 2014, the chief curator of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. Many were shocked when Molesworth was suddenly let go from her position at MOCA, coming off the heels of the highly successful 2017 Kerry James Marshall retrospective, “Mastry,” which was co-organized with curators from the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. MOCA initially said that Molesworth had stepped down of her own accord, but it was later revealed that she had been let go, possibly due to not seeing eye to eye with the museum’s former director Philippe Vergne.

Molesworth came to art as an outsider, sneaking out of class in high school to visit the Met, and notes in the introduction that “it never occurred to me that I might one day live in this world: the world of museums and galleries.” She was curious about art, and about its complexities: “An artwork is a network of ideas, feelings, form, history,” she writes, and her desire to understand art leads her to write about it, to “undo” this network.

This offering as to why she writes about art feels like a natural way to introduce readers to the 24 essays that follow, exploring the works of a variety of artists, including Lisa Yuskavage, Simone Leigh, Ruth Asawa, Noah Davis, and Marcel Duchamp—who receives his own section, as Molesworth wrote her dissertation about him—along with her insights and thought process in viewing them. Her essay on the paintings of Dike Blair opens with a memory of a dive bar in Ithaca, New York, that she frequented while getting her Ph.D. from Cornell. This idea that art allows the viewer to time travel is yet another key element of her introduction.

In “Deana Lawson: Nation,” Molesworth focuses on a photograph by the artist that was exhibited as part of a solo show at the gallery Sikkema Jenkins & Co. As she had long been familiar with Lawson’s work, Molesworth is still surprised by her reaction to the photo. While the image appears candid, Molesworth notes that it’s stage-directed: One of the subjects, a Black man, wears a strange mouth guard that Lawson brought to the shoot. Appearing in the upper right-hand corner of the photo is another photo, that of a set of George Washington’s dentures. Molesworth’s writing takes us out of the gallery and into her own account of learning how Washington purchased teeth, possibly those of enslaved people, for his dentures. Then she opens up many questions about this information—and about the history of America and the lore around Washington—turning them around in her mind and on the page for readers to follow.

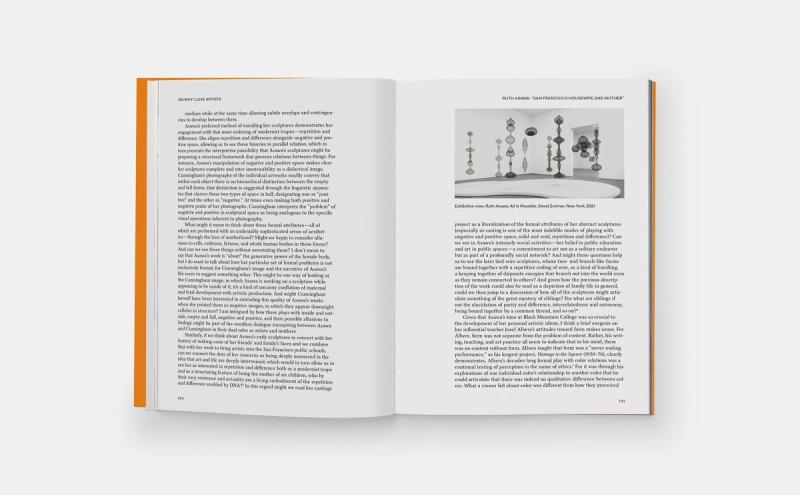

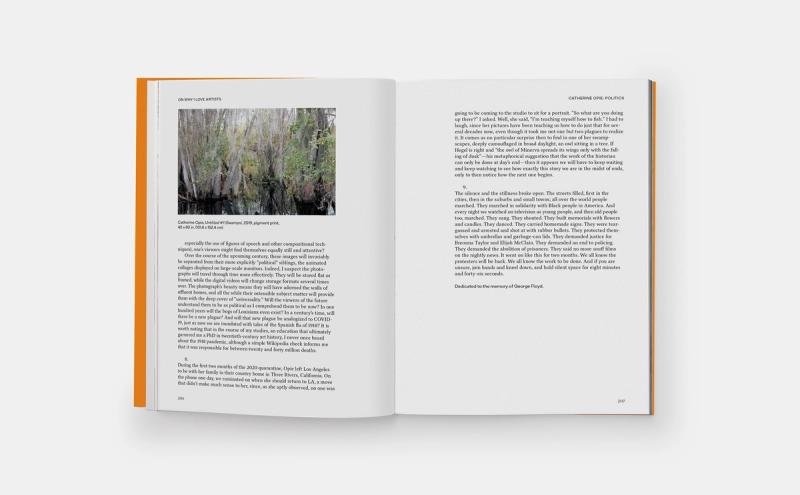

The act of viewing art is never the end point for Molesworth—it’s always the beginning of the experience. Her essays are a continuation, a follow-up after the fact, that offer a new way of seeing. A handful of texts in Open Questions are paired with newly written postscripts in which Molesworth reflects on the preceding essay and provides context on her thoughts. Many of these postscripts appear in the section “On Why I Love Artists,” which features essays each focusing on one artist, some of which were commissioned to appear in exhibition catalogues for one-person shows. I appreciated these updates, and the fact that Molesworth used this space to look back on her work, and at times her personal history. Her postscripts are another way of continuing the conversation.

Mostly, I came away from reading Open Questions thinking about the way I view art, and about the spaces in which art is shown. Sometimes information is provided to the audience in the form of wall text or a catalogue, but another part is played by the individual and their personal experience. Molesworth doesn’t aim to lecture her reader, but instead engages them and points to the things that “pleased, confused, bothered, disturbed, or confounded” her. She states in the book that she hopes her essays help viewers to be curious in front of works of art, and that—borrowing a phrase from Duchamp—“a work of art is completed by the viewer.” Open Questions is more than a collection of art writing; it is a meditation on seeing and feeling, on connecting and thought-making. Molesworth gives that power to the viewer, and in a way, gives them the chance to be the curator themselves.