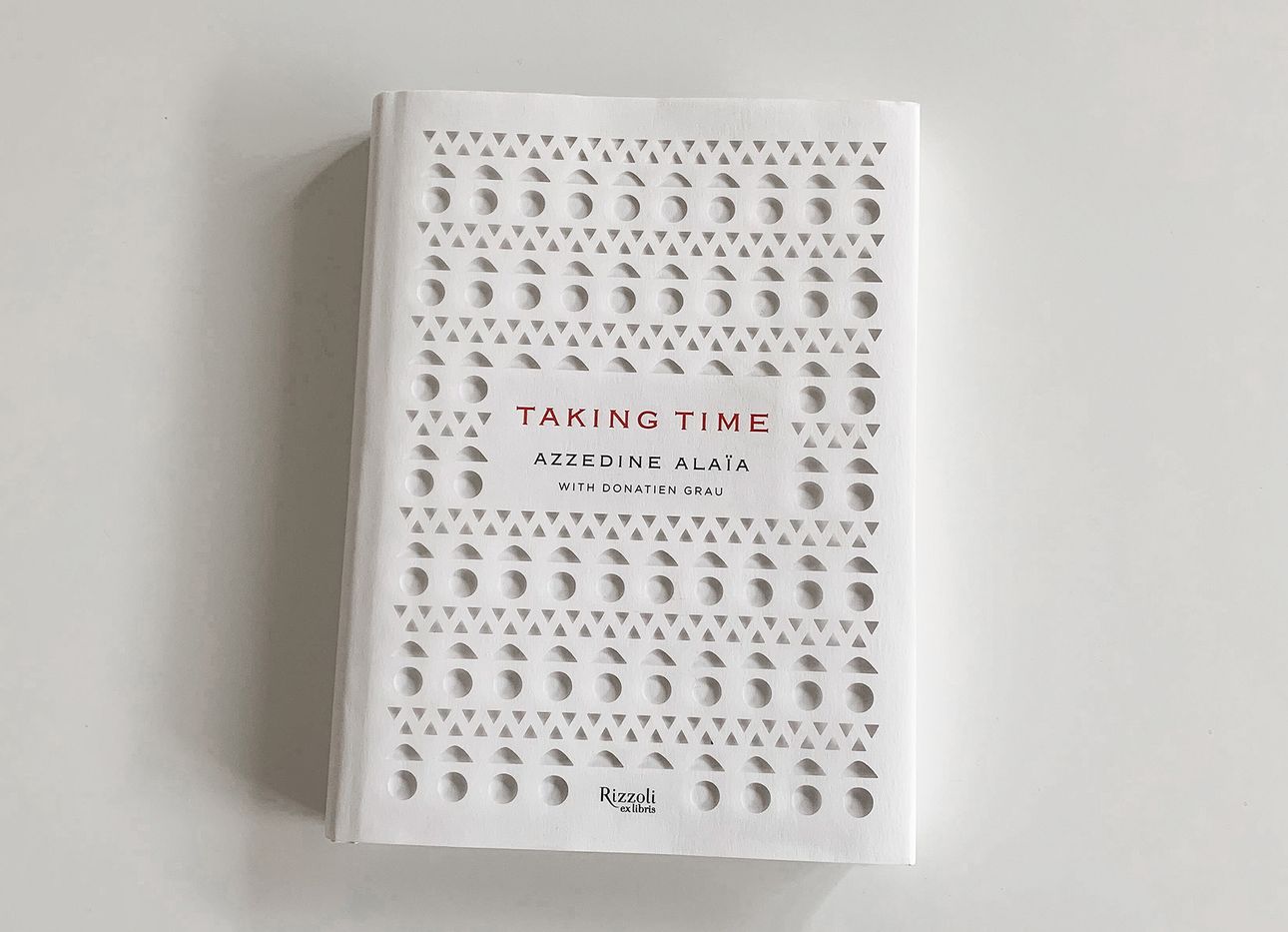

Azzedine Alaïa’s Ruminations on the Value of Taking Time

Curator and critic Donatien Grau—who was on our At a Distance podcast last week—talks with us here about the new book he produced in collaboration with the late couturier Azzedine Alaïa, Taking Time (Rizzoli), a series of wide-ranging conversations on art, time, and creativity. Among the visionary voices featured—most of whom were close friends of Alaïa’s—are Ronan Bouroullec, Isabelle Huppert, Charlotte Rampling, Julian Schnabel, and Robert Wilson.

How did this project first begin, and what led to the idea of presenting it as a series of conversations about time?

Azzedine always fought for people to be able to make things at their own pace, and he was a paramount example of this. This was something that he had been thinking about, struggling with, and advocating for decades. Then, around 2012 or 2013, it was something he wanted to make people aware of—that there was a need to change how we approach time and creativity, and, progressively, he wanted to bring in some of his friends and fellow travelers from all different disciplines to share their stories, visions, and insights. Initially, he wanted to host great events to discuss the pressures exerted on contemporary creativity, but thought that might actually become a source of pressure. Instead, we began to host these conversations over the course of three to four years, with the idea that they would eventually become a book—his manifesto.

In a way, what I have been is an instrument for the realization of Azzedine’s project, rather than an author of it. It was Azzedine’s idea and project, and at the time I was very lucky and fortunate that he chose me as his steering partner. After his passing, I made sure that the book would come out and reach the public.

In the book, you write that each of the interviews is “like a couture dress made of words.” Could you tell us a bit about how you and Azzedine arranged each of the pairings?

Azzedine had this extraordinary community of friends and practitioners that gathered around him, and the basis of this community was really a sense of mutual respect for people who may be very celebrated, and may be famous, but who were also hardworking. This idea that you work your way through life, doing things your own way and making things, was very important to their interactions.

Every participant is somebody he was friendly with, admired, and respected. As we invited people to join the project, we would ask each of them to come up with somebody that they would like to speak to, and often the person was another friend of Azzedine. That was the case, for example, with the conversation between Isabelle Huppert and Robert Wilson. It was a very organic process of constructing these conversations: Sometimes they had very personalized ideas, and other times they wanted us to suggest people to speak to. From the beginning, it was very important to bring in contributors from different worlds and cultural spheres to really share their own experiences, and, in a way, it was also important that the project be performative, in that we were talking about taking time, but also taking time as we were doing it.

They were all moderated by Azzedine and me, so we were both present, and they were all hosted around his kitchen table, which is a very important and iconic part of his house. He would host his friends and collaborators every day, and easily have twenty to forty people over for lunch and then at dinner—and famously, he always left an empty seat for one of his friends who might show up and want to join them. There was a sense of purpose that animated the whole community—something, I think, that is quite an important message today, which is to claim a form of ownership of one’s time.

As a critic and historian, you’ve written about art and creativity. How did working on this book for several years change your understanding of both?

Being with Azzedine, as a friend and as a collaborator, has completely changed the way I work and think. The way people talk about creative communities from the 1920s—people around Jacques Doucet or around [Paul] Poiret—what Azzedine did was exactly that, but you weren’t reading about it in books, you were experiencing it for real, and with a level of intelligence and precision, as well as a deep human connection.

Obviously, everybody who’s worked with him and has been close to him has had their vision completely changed by him. He was somebody who would completely challenge everything you could see. He was an extraordinary creator and maker, as well as somebody who had impeccable taste in other people’s artworks and creations.

With the ongoing Covid-19 slowdown, people around the world are adapting to a new, altered sense of time, taking stock of the present and rethinking the future. How has this period changed your perception of time and relationship to it?

It’s quite fascinating to see the book come out at this very precise moment in history. As Naomi Campbell writes in the foreword, Azzedine was very often ahead of his time, even if you didn’t know it at the time when he was doing it. Obviously, when he passed away, in 2017, we didn’t plan on the book coming out in 2020. We didn’t plan on it coming out two weeks before the Met Ball themed around time [which was supposed to take place next month, but has been postponed], and we certainly didn’t plan to publish it during a world pandemic. The values that Azzedine advocated for—this emphasis on creating one’s space, owning one’s time, and being aware of the industry pressure as something that tends to devour you, and making yourself mindful of the lessons from older generations, as well as from the younger generations—these are all lessons that are really important right now.