Dacher Keltner on Why We All Need Daily Doses of Awe

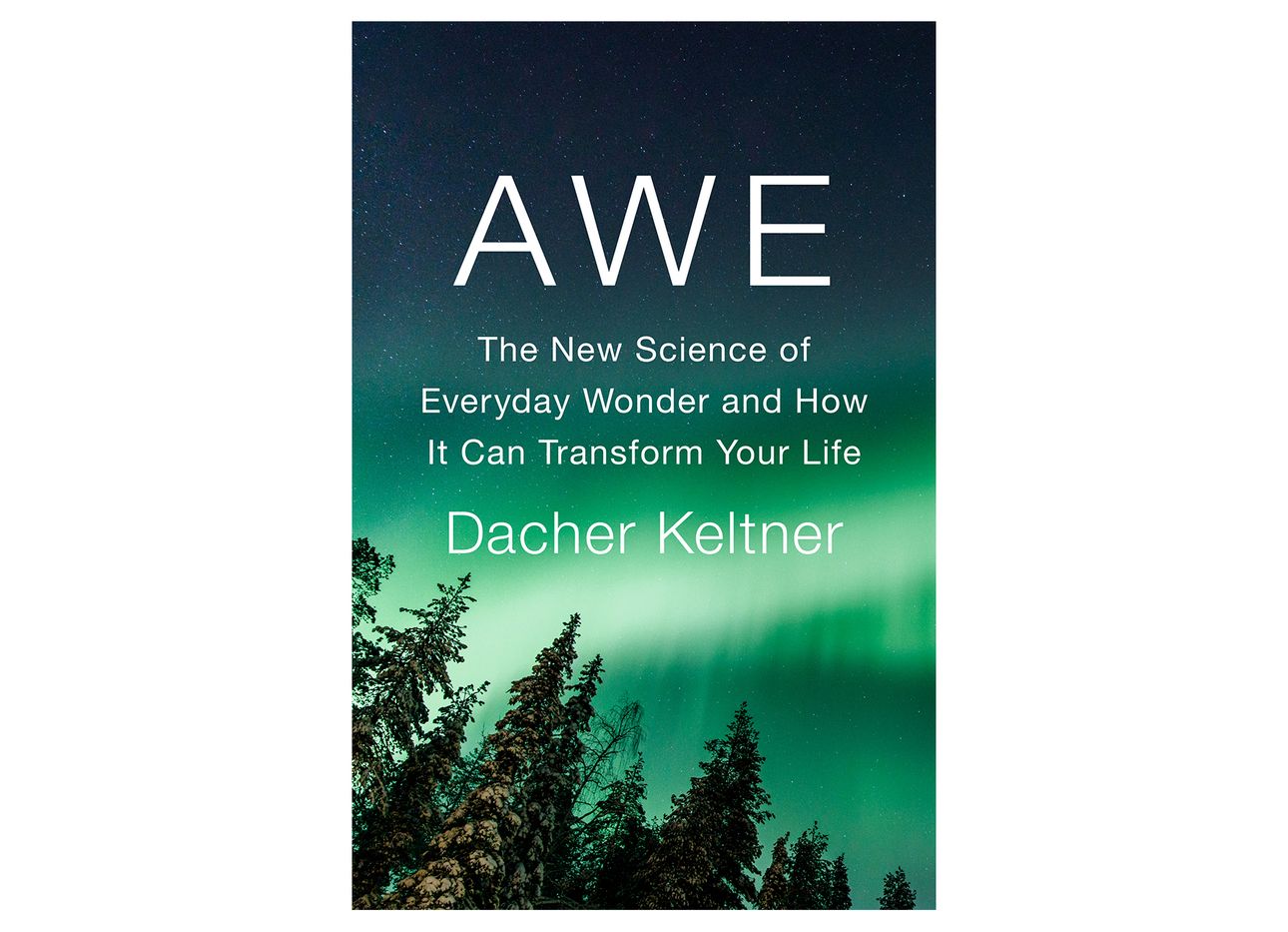

For the past 20 years, Dacher Keltner, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, has been teaching the slippery subject of happiness. Now, at last, he believes he has landed on a profoundly simple, scientifically proven method for achieving it: “Find awe,” he writes in his extraordinary new book, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life (Penguin Press).

As Keltner discusses on the latest episode of our At a Distance podcast, awe transforms us, opening our bodies and minds up to the vast wonders of the universe in a way that plants us firmly in the present. Awe is healing. It brings about joy and meaning, and can even lead to a more rigorous level of thinking. Keltner’s book makes clear that this isn’t some hippyish, woo-woo theorizing; combining both empirical research and rich scientific data, he makes a strong case for why awe should be considered a staple in our daily diet. “You’ve obviously got to have food and water and sleep,” he says on At a Distance, “but awe is right up there.”

Below, a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

Click here to listen to the full interview on our At a Distance podcast.

You define awe as “the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your current understanding of the world.” How did you come to this particular definition? Awe seems almost indefinable, but you manage to capture it.

[Laughs] Yeah, it’s funny. Everybody says that awe is indefinable, that you can’t capture it with language, that it’s ineffable. And yet, everybody tries to define it in their old traditions in philosophy and religion and spirituality.

I came to that definition through a couple of pathways. One was the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke, from the eighteenth century, who said, “Awe, or the sublime, is about power, or vastness and mystery,” or what he called “obscurity”—we can’t make sense of it immediately. That felt right to me. The experiences of awe I’ve had really had that overwhelming quality to them. I couldn’t make sense of them. So, in the book, I move toward a more colloquial definition: The best way to think about awe is that it’s really about the vast mysteries of life.

You break the book into what you call “the eight wonders of life.” How did you go about creating this structure and identifying these particular wonders?

Awe is such a rich topic historically. It’s about religion and music and nature and psychedelics and political protest and charismatic leaders—all this stuff.

What we decided to do in my lab is survey—actually, more than survey, we gathered stories of awe from twenty-six countries, ranging from China to Mexico to India to Brazil to the U.S. to Japan to Indonesia. “What made you feel awe? When did you last encounter it? What was vast and mysterious?” What we uncovered, once we translated the stories, after a couple of years, is what I call in the book “the eight wonders of life.” It kind of aggravates people: “Ah, c’mon, eight?!” But indeed, they cover about ninety-five percent of the stories. They are: people’s moral beauty, kindness, and courage; nature; collective movement (cheering at a rally or a football game, or doing rituals in a service, or dancing); then you get to music, visual design, and religion or spirituality; and then to two odd ones, big ideas and life and death.

I love how, for the collective one, you describe it as “collective effervescence.”

Yeah, that’s from Émile Durkheim, this great sociologist. He’d observe these small-scale society people, and when they would practice their spirituality, they’d dance and move together and start vocalizing together. That really is the heart of this transcendent, ecstatic experience: Dancing with people, cheering with people, singing with people, choirs, just brings about this bubbling, electric, tingly feeling, together. That’s awe.

I found it really interesting to learn that lab studies have shown that awe actually leads to more rigorous thought.

That surprised me, too!

I was wondering, why is this exactly? How would you explain it?

Thanks for picking up on that. A lot of people feel like, once you feel awe, you’re kind of stupefied, you’re glassy-eyed, you’re like, “Ohhhhh.” And, you know, maybe that’s in the first moments or first seconds of awe—you see a flashing light in the sky and you don’t know what it is. But what we’ve got to remember is that emotions unfold in processes, and awe unfolds into a state of wonder, which is about curiosity and seeking explanation. In the state that awe produces, people are more rigorous in how they think about things. They evaluate evidence more carefully. They are better scientists. They do better in school. They are more sophisticated in their political reasoning. Those are all empirical findings. Brief experiences of awe sharpen your reasoning and intellect.

I have to bring technology into this, particularly screens. You describe how so many of us are operating with an “overactive default self, augmented by self-obsessed digital technologies.” The result, of course, is anxiety, depression, and self-criticism. Is experiencing more awe a way out of this loop? Is awe a potential solution to the things that ail us?

Yeah, it’s astonishing. We’re just starting to make sense of this at the sociological level. I recently visited the Louvre, and I went to see the Mona Lisa. Now, when people see the Mona Lisa, they don’t really look at the Mona Lisa. They take photos of themselves in front of the Mona Lisa. It’s absurd. They’re going into this room with this great painting by Leonardo da Vinci, and instead of looking at the painting and the mystery of the smile, they’re taking a picture of themselves. That’s emblematic of what sociologists are worried about, which is that, in a lot of cultures, people are just too focused on the self: They take pictures of themselves, they look at their Instagram likes, they compare their Instagram likes to other likes, they are self-critical, they are worried about their bodies, they ruminate too much at night about themselves. This is a historical aberration. The mind needs to be aware of the self and track it to succeed in the world. But we need to be aware of the context, we need to be aware of other people, we need to be aware of the environment. And all of this self focus takes us away from that and has led to rates of anxiety and depression that are really high.

When I started to learn about people’s experiences of awe, they would commonly say, “God, I forgot about myself. I disappeared. I dissolved. I couldn’t hear that self-critical voice.” We’ve now got a lot of data that speaks to that. That’s part of why awe is so good for you—it just shuts down what Aldous Huxley called this “nagging, neurotic voice” that’s always like, “Agh! Dacher, you’re not working hard enough, you’re not successful enough. Your bank account isn’t good enough. Oh, look, you’re overweight!” Awe quiets all that chatter down and says, “Hey, look and see what’s big out there that’s worthy of your attention.”

I would say that awe takes you away from the self—and the cell phone.

Ahhh, and we should just call it the “self phone.” [Laughter]

This makes me think of a meme I recently saw that shows Michael Jordan shooting a three and LeBron James shooting a three, and the contrast between the two audiences. In the Michael Jordan era, the audience was all on their feet, screaming and clapping, and in the Lebron era, everyone’s still seated and staring at their phones, taking pictures.

Ugh. There are really deep issues at play here. One of the things awe often brings about—with music, or watching dance or a political rally or a sporting event—is that we all share our attention on that event, and that’s really important. Michael Tomasello, this important developmental psychologist, has said that that ability to share attention—that you and I are aware of the same things—is a miracle. It’s very important to human beings and consciousness. The cell phone disrupts it. We all go to an event, we put up our phones to record it, and we’re not understanding that we’re all sharing the experience of that moment. So it’s serious. Awe brings this into focus.

Could you talk about how another TEK—T-E-K, traditional ecological knowledge—comes into this?

Well, in many Indigenous societies, we felt like we were part of ecosystems. Then, as the Western Industrial Revolution kicked into gear, we began to fear nature. People didn’t like to go outside; they didn’t hike in the mountains. Then, with the rise of Western European technologies, we came to believe that we own nature: We commodify it and we exploit it. That has led to where we are today with overconsumption, burning fossil fuels, et cetera. Awe shifts our awareness of nature to traditional ecological knowledge: There are these ecosystems out there. They are complex processes of different species interacting with each other. I’m one of many species in this system, and we’re all competing and collaborating toward some sort of homeostasis. That is such a radically different view of nature, where we revere resources, and we see ourselves as potential collaborators with other species.

Right. Systems thinking. Which became such a focus of so many people during Covid, too.

Really?

Well, that’s my hope—that this slowdown allowed people to think a lot more about systems thinking. It’s been a focus of a lot of the episodes on this podcast, including a conversation we had with Dr. Suzanne Simard, who talks all about the roots of trees and “the mother tree.”

That’s what awe does. Systems thinking is a major achievement in cognition. Some people believe it’s one of the defining human strengths. It’s like, “There are systems out there—cultural systems, spiritual systems, ecosystems, social systems—and I’m part of them. How do I figure it out?” Awe opens your eyes to that. One of my favorite studies is, you get people to feel awe about, say, viewing nature imagery. They’re like, “Wow, that’s so amazing, those big waves and flocks of birds and patterns of light, and trees and ecosystems or fungi.” And they are more aware of how they’re part of a social system. They’re like, “Oh, wait, I’m not a solitary individual. I’m part of this network that’s connected in different ways.” We need that. Kids need that.

I find it refreshing that you describe awe as “a basic human need.” Which really brings it down to earth. For me, reading that caused such a profound perspective shift: that awe is something that we shouldn’t wait for, but in fact should seek out.

That comes out of science. There was a really important argument made recently, to great effect, in Psychological Science, that we have a need to belong. It’s good for our health. It shows up early in kids. It’s part of our evolutionary history. And I think the data are now in place to make the same case for awe. It’s about a human being being alive.

As I thought about this broader argument of “what constitutes a need?” awe fit the criteria. Kids show awe right away, just like they acquire language and learn to love certain foods and learn to connect to caregivers. Kids are just wild with awe. It’s part of their intellectual development. It’s good for your body. It’s really good for your immune system to get out into the woods or listen to music and feel awe. And then it’s good for your fitting into society. With a little bit of awe, you collaborate more, you build stronger ties. These findings tell us that awe is as vital for children as it is for adults. You’ve obviously got to have food and water and sleep, but awe is right up there.

You write that “one of the most alarming trends in the lives of children today is the disappearance of awe. We are not giving them enough opportunities to discover and experience the wonders of life.” You reference this great 1956 essay by writer and conservationist Rachel Carson called “Help Your Child to Wonder,” which is basically a presentation of an awe-based approach to raising a kid. What are some solutions, as you see it, for creating a greater sense of awe in children?

Oh, man. It was so astonishing to raise two daughters in this era. I was raised in the late ’60s by counterculture parents. I didn’t learn too much in high school, to be honest. [Laughs] But I caught up. What my parents taught me is how to find awe.

When I raised my daughters, the culture was almost the antithesis of what Rachel Carson talks about. She talks about getting outside as fundamental. She takes her nephew out into this rainy storm. With parenting today, kids are spending more time inside on iPads, looking at images of nature. If you read the essay, it’s really just about distrusting language and concepts. When I was [raising my kids], I remember a lot of parents saying, “Oh, it’s really important to teach your kids words and to always label stuff.” I was labeling the hell out of everything. Kids need to learn about phenomena on their own, independent of a parent’s language.

In the essay, Rachel Carson just kind of wanders, in a freeform way, with her nephew. A lot of our kids’ education doesn’t allow for wandering. It’s all focused on tests and scores. She talks about mystery being the engine of what we need to pursue in knowledge. That’s not as much a part of curricula today. It’s such an important essay. Thank you for flagging it.

Neuroaesthetics is another area I wanted to touch on, particularly beauty and art and visual design. At the city-planning level, there are all of these homogeneous nonspaces being foisted upon us around the world, so I think it’s important to emphasize that creating beautiful, thoughtfully constructed buildings and public spaces that encourage greater use and deeper engagement can actually promote collective health and well-being. I think what your book shows is that these are not just nice things to think about and consider. This is science. There are studies that show that when you’re in a beautiful space, you’re almost becoming a better, fuller person.

You’re capturing exactly why I wrote this book. Awe-based design is a deep human tendency in our greatest achievements—the Mayan pyramids, the cathedrals of Europe, the glass windows at the Sagrada Familia, Japanese gardens. There are principles there. We know that urban landscapes have effects upon people’s health and well-being, and I review that evidence in the book. It just urges us to really think about what you’re proposing, which is: There are really clear principles of awe-based design, about degrees of vastness and hints at mystery; and shifts in attention, from the small to the vast; and mystery built into it, et cetera. And there is data that shows that in places with those design principles, the citizens are happier and there’s less crime.

What’s been exciting is that people are starting to think about this. I was talking to an architecture firm in Sweden, and they were saying, “We are starting to design buildings for awe.” I just had somebody reach out who was interested in palliative care facilities and designing for awe and beauty. We know how to do this, and somehow we’ve lost sight of this. I hope our conversation and the book inspires people in that direction.