Antwaun Sargent on the Power of Contemporary Black Art

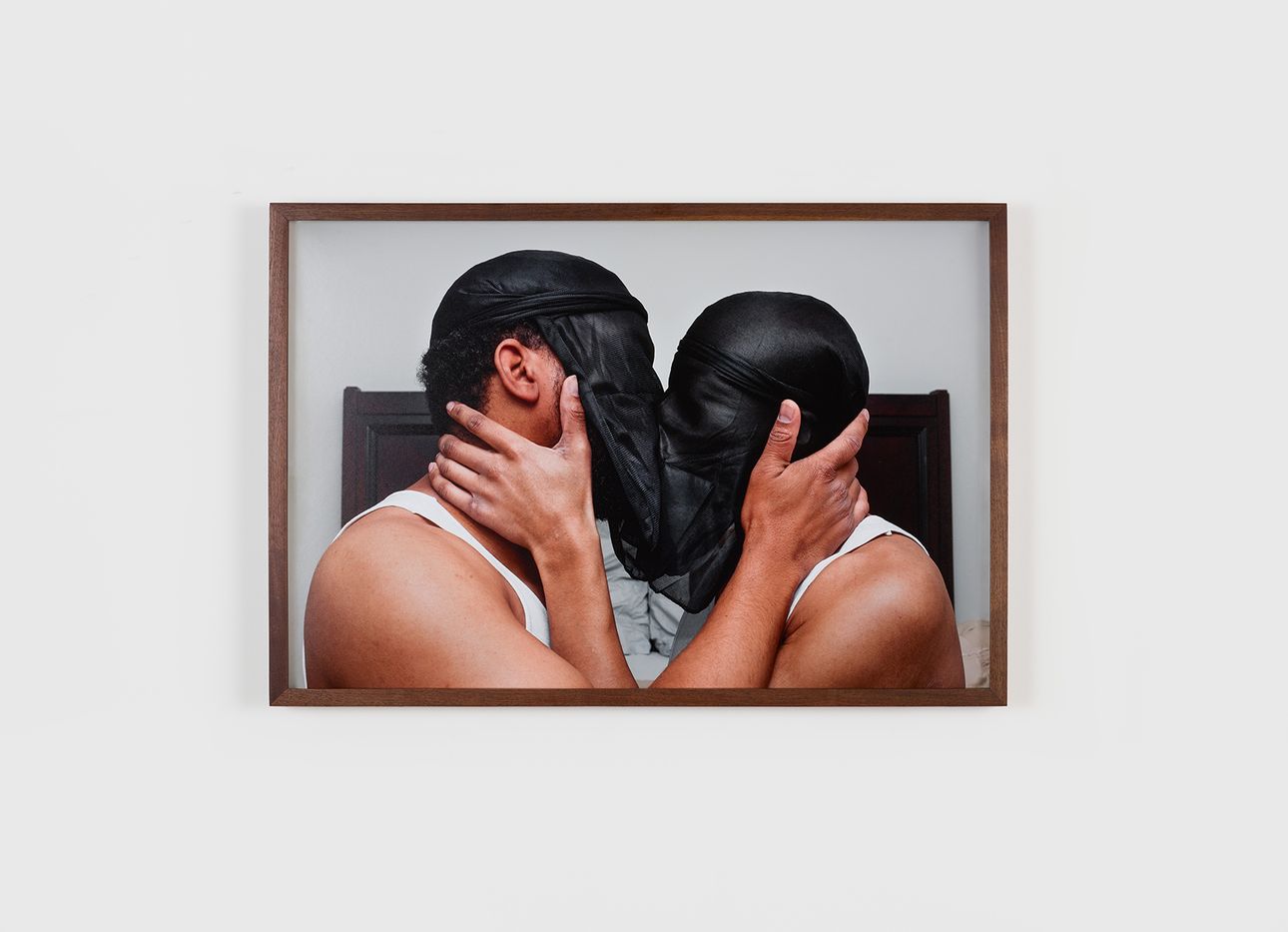

An art critic, curator, and author, Antwaun Sargent has become a leading voice for a rising class of Black contemporary artists practicing today. Less than a year after publishing his first book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion (Aperture), Sargent is serving up his next, as the editor of Young, Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists (D.A.P.), highlighting the works of Black artists from the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art. An exhibition of the same name is currently on view at the Lehmann College Art Gallery (which is temporarily closed due to Covid-19) in the Bronx, New York, and is set to travel to a number of venues through 2022.

We recently caught up with Sargent to discuss the process of editing the book—which counts curators Thelma Golden, Lauren Haynes, and Jamillah James among its all-star roster of contributors—and how collecting can be a form of resistance, as Black artists continue the fight to claim space in the various institutions of the art world.

A lot has changed between the release of your first book and this one. What’s it been like working on this project over the past year?

Originally, this book was supposed to come out sometime this spring, but, as you know, we were adjusting to our new reality and it was pushed back. The art world is sort of coming back to life now, and it’s good to be able to have this conversation about a new generation of artists. This book is not only a document of a family’s significant collection of work by Black artists, but also of how we have moved, over the last decade, to a world where we’re seeing more and more Black artists being collected by museums, and seeing more and more Black artists’ concerns being expressed artistically in public domains.

How do you hope to shape those conversations?

One of the things that’s important in a project like this is to try to map the ways in which we have come to know these artists, and the ways in which the artists ended up in Bernard [Lumpkin] and Carmine [Boccuzzi]’s collection. For me, that immediately meant thinking through the different curatorial, artistic, and critical voices that have helped champion and develop the careers of these artists—and that also meant thinking about their immediate predecessors, the artists who might provide inspiration for the practices of this new generation. We have a cornucopia of voices that give a real sense of, as I like to say, how the sausage is made. Because, far too often, the art world is a very opaque place: You don’t really know the process of how work ends up in certain collections and, in turn, how those works end up before the viewing public.

It takes a village.

Exactly. It’s also sort of a check on the ways in which museums and the larger art world operate, because the story that we get—that museums woke up one day and said, “Oh, this work is really important”—isn’t really the case. There’s a great deal of advocacy that has had to happen in order to bring museums around to the power and possibility of Black art.

How did you first meet Bernard Lumpkin?

I’ve known Bernard casually for some time, because I would see him everywhere, at all the same shows, and we would joke about that. [Laughs] But I had not known his philosophy around collecting or patronage. I would go over to his and Carmine’s apartment and spend hours and hours interviewing him, and, frankly, challenging him, on a lot of topics. He was actively collecting when we were working on the book, so we got to have some really in-depth conversations about that, but also about how to protect the work, and how to do that with a certain set of ethics. Like, how early is too early to collect or sell a work?

We also spoke about the philosophies around his roles on the boards or acquisition committees at the Whitney, at the Studio Museum [of Harlem], and at the MoMA. What’s the role of a trustee? What’s the role of a committee member of a museum in the twenty-first century? Just having those really complex conversations, I think we both walked away with different understandings of those roles, but also as to my role as a writer. Some people would remark, “Why do a book like that? Doesn’t it explode the lines between criticism, artists, and collectors?” And I think that, you know, the art world has had an old way of doing things that excluded a great deal of people—many of whom look like me. I’m just not satisfied with that old way of thinking, because it was racist and sexist, and got us an art world where ninety percent of the fucking artists in museums are white straight men.

Looking back, what’s been the most fulfilling aspect of working on this project?

One of the sentimental aspects has been thinking back about my move to New York ten years ago, at age 21, and having no idea that the art world existed in the way it did here. I certainly didn’t have any clue that I would ever play a role in it, write about artists, or anything like that. Being brought into the art world by my friend JiaJia Fei really opened me up [to it]. She would take me to museums and artists’ parties, shows, and openings, where I’d meet artists like Eric Mack, Jennifer Packer, and Jordan Casteel—this whole generation of artists we’re talking about.

I didn’t have to learn about a great many of these artists because I knew them, I’ve written about them, and have grown up and come up with them. So in a way, this is a crowning of my first ten years in New York, and of the people who made this city livable for me. The city, of course, is a place that’s teeming with possibility, and to me, very magical in that way. As we talk about “the end of New York” or whatever [laughs], I know that my community is very much still here, and very much rooted here. That sort of reminder, during this time of protest and pandemic, is really important—to know that that world, in some way, is here, and will continue.