A Fictional World Created by Toyin Ojih Odutola Calls Into Question Real-Life Systems of Power and Gender

New York–based Nigerian artist Toyin Ojih Odutola often uses her creations—eclectic multimedia drawings and works on paper—to tell fictional stories that offer new ways of thinking about real-life issues. The pieces she created for her solo exhibition “A Countervailing Theory” currently on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. through April 3, 2022, are possibly her most elaborate experimentation with form and narrative to date. (If you’re in town, we also recommend stopping by the Phillips Collection to view the exhibition “Intersections,” a new body of work by artist Sanford Biggers, who was the guest on Ep. 66 of our At a Distance podcast, on view through Jan. 9, 2022.) Commissioned by the Barbican Art Gallery in London, where it was presented from August 2020 until this past January, the show features 40 large-scale, monochromatic drawings that act as an engaging storyboard for an allegorical tale that considers the ways in which we engage with systems of power, culture, gender, and history.

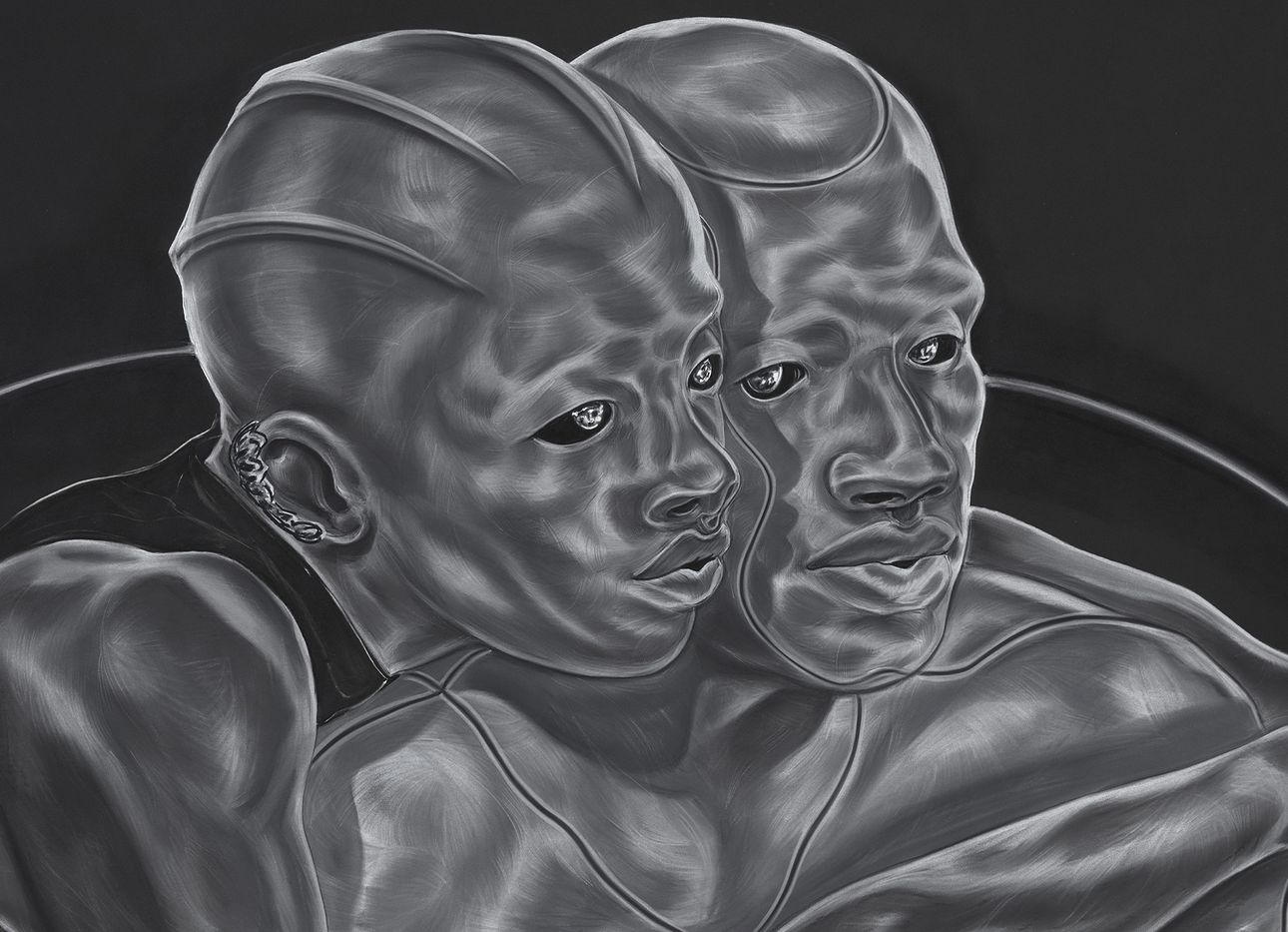

Ojih Odutola does this by flipping the script in almost every way. The show chronicles a fictional, ancient Nigerian civilization where heterosexuality is forbidden, and where male laborers, known as the Koba, serve a ruling class of female warriors, called the Eshu. Alternately tranquil and violent, life in the realm plays out in the romantic (and ultimately tragic) relationship between the story’s central characters: Aldo, a male humanoid from the Koba working class, and Akanke, a female Eshu warrior. It all unfolds within a surreal landscape informed by the swirling rock formations of the Plateau State in central Nigeria. (The ornate scenery’s appearance is echoed in the way that Ojih Odutola, who is known for the detail she gives to the texture of her Black subjects’ skin, portrays markings on the bodies of her characters.) Even the artworks themselves take an inverse approach to their creation: The artist worked on black surfaces and drew on them with ivory-tone charcoal, pastel, and chalk.

Moving through the show, viewers will likely notice familiar power dynamics and hopeful signs of change. The drawing “To the Next Outpost” (2019), for example, depicts Aldo working in a field in the foreground, while Akanke, stylishly dressed, stands above him with her back turned, surveying the manicured land beyond. “An Understanding: A Lesson in Listening” (2020) shows Aldo speaking to Akanke—who listens intently—and in doing so, momentarily suspends the realm’s social hierarchy. Elsewhere, references to history (as in a panel that portrays the faces of Aldo and Akanke chiseled into a stone monument) and pop culture (as in a drawing in which Koba men are shown krumping, a style of hip-hop dance that involves rapid, exaggerated movements of the arms and legs) abound. To further bring the alternate existence to life, a cinematic soundscape by sound artist Peter Adjaye translates the drawings’ strange, spectral visual language into a sonic experience—including running water, throbbing electronics, classical strings, and West African instruments—that hums throughout the gallery walls.

Ojih Odutola presents each drawing as a scan of a stone tablet unearthed during an archeological dig—a way of encouraging viewers, perhaps, to approach the works as objects of curiosity and reflection. Her questions about who gets to tell stories about the world, and about the implications of power, may not be explicitly answered—but that’s not the point, as the conclusion of the show suggests. There, the wall text includes a note from a fictional Nigerian archaeologist, who supposedly discovered the exhibition’s contents. “We appreciate and welcome all those who are willing to engage in this fascinating discovery with us,” the text reads, “despite not knowing the full extent of its meaning.”